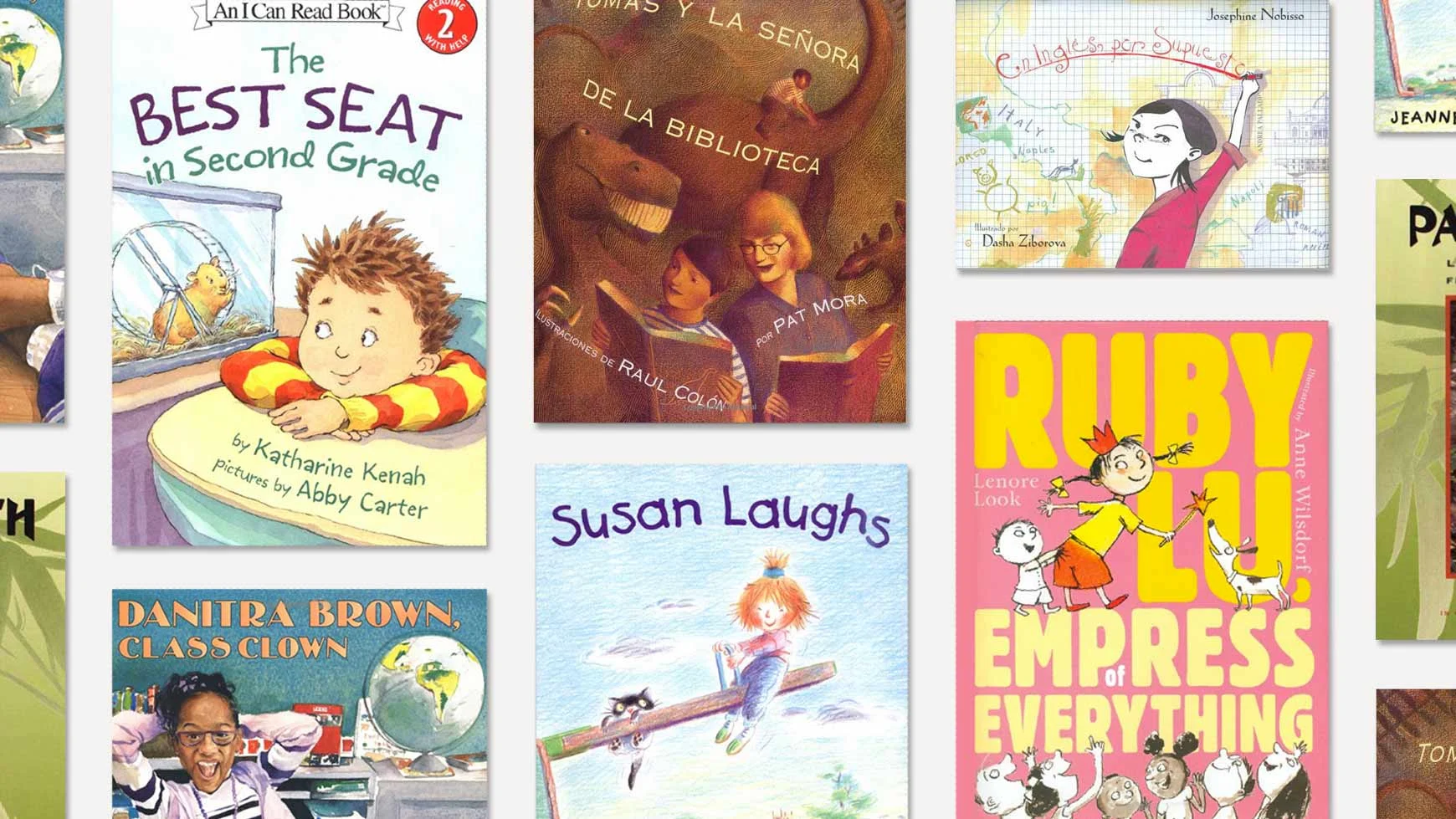

717 results for: "back to school"

Back-to-school stress: Why I believe self-advocacy can help

As president of Eye to Eye, the largest national mentoring organization for kids with learning and thinking differences (and an Understood founding partner), I get to talk to a lot of parents. Right now, the biggest thing on their minds is back to school.Academics is a big concern for many parents. But there’s also a social-emotional side of the new school year, especially the stress and anxiety that kids face.I understand this firsthand because I went through these struggles as a kid. I remember my ninth-grade year as being a particularly tough back-to-school transition.During the first week of ninth grade, my English teacher assigned us Shakespeare’s Macbeth to read.“Double, double toil and trouble; Fire burn, and cauldron bubble.”—Macbeth, Act 4, Scene 1I have dyslexia and ADHD, and I started worrying that reading this play was going to be impossible for me. How was I going to do this? I could feel my hands shaking and my palms sweating — my stress level went through the roof.It didn’t help that this was my first year of high school. I was in a different building than last year, with new classrooms and a new locker. I didn’t know my way around.In middle school, I’d been one of the oldest students. The teachers knew me. I had a support system of people I could talk to. Now I was a lowly freshman, starting all over again. It was scary and nerve-racking.But it was an opportunity as well. This was a chance for a fresh start. And soon, someone would give me the chance to talk through how I was going to handle ninth grade.After assigning Macbeth, my English teacher pulled me aside.“Marcus,” she said, “I’ve seen your IEP. I know you have dyslexia and reading issues. And I know what accommodations the IEP provides for you in class.”I was quiet. Then she continued, “I know all that, but I’d like you to share with me in your own words: What’s going to help you be successful in my class?”I was a little stunned. This was the first time I’d had a chance to talk with someone who wasn’t my parent or a special education teacher about the way I learn.She gently nudged me, and then I opened up.Yes, I told her, I love to participate in class and share my ideas, but please don’t call on me to read aloud. I’m not good at it, and reading aloud will terrify me and ruin my focus in class.As we talked, I started to remember things that had worked for me in middle school. I do better, I recalled, when I sit in the front of the class. It helps me pay attention.“What about the reading assignments?” she asked.Oh yes, I said, I’m going to have difficulty keeping up on the reading. Suggestions popped into my head — maybe I can get the assignments ahead of time so I can start early? Maybe there can be understanding if I’m a little behind because it takes me longer to read?She listened to me and nodded. My stress level started to go down.It’s not like everything was instantly better. I still struggled, and I didn’t have everything figured out. For instance, I wished I’d embraced audiobooks in ninth grade as a way to keep up with reading. It’s a tool I use every day as an adult!But just the act of talking about what I needed made me feel empowered and more confident about school. My teacher made it OK for us to discuss what would have been frightening for me to think about alone.If your child is struggling in school, he may find it really embarrassing and scary to speak up. These self-advocacy skills aren’t easy. Students with learning and thinking differences need to practice them over and over again, and consistently.The good news is that the start of each school year is a chance to get your child talking about their needs. It’s a natural time to do this because everything is new. And for many kids, talking about the changes helps reduce stress and anxiety.How do you go about getting your child talking?In ninth grade, it was a teacher who gave me a push. In previous years, my parents had done so. In later years, I initiated these talks. In fact, I took these skills into college and the workplace.Every kid is different. Some are natural talkers. Others need hand-holding from parents and teachers. Many kids can benefit from having a mentor to help guide the way. Personally, I’ve always felt that these conversations are easier if you schedule them right before doing something fun, like going out for ice cream or shopping for new sneakers.The key is to start somewhere, no matter how small. And then keep talking. Self-advocacy is an essential skill that takes years to learn.

In It

In ItBack-to-school action plan: Setting goals and getting organized

Starting a new school year can be overwhelming, especially for kids who learn and think differently. Get tips for making it more manageable. For many families, the new school year brings a real mixed bag of emotions. There’s the excitement of a fresh start combined with jitters about all of the unknowns. For families of kids who learn and think differently, there may be IEPs or 504 plans, and new teachers to connect with about all these things. It’s a lot to think about — and to navigate.In this episode, hosts Gretchen Vierstra and Rachel Bozek talk with returning guest DeJunne’ Clark Jackson, an education consultant and parent advocate. She’s also the mom of two kids, one with an IEP. Tune in for back-to-school strategies that have worked well for DeJunne’ and her family. Find out how she sets goals with both of her kids, keeping in mind their strengths and challenges.Related resources Download: Back-to-school update for families to give to teachersDownload: Goals calendar for kids who struggle with planningMy kids have different strengths and challenges. Here’s how I set goals with them.Hear more from DeJunne’ in this episode about parent-teacher conferences from last season Get back-to-school tips from executive function coach Brendan Mahan in this episode about building executive function skills Episode transcriptGretchen: From the Understood Podcast Network, this is "In It," a podcast about the ins and outs...Rachel: ...the ups and downs...Gretchen: ...of supporting kids who learn and think differently. I'm Gretchen Vierstra, a former classroom teacher and an editor here at Understood.Rachel: And I'm Rachel Bozek, a writer and editor with a family that's definitely in it.Gretchen and I have been away from our microphones for most of the summer, apart from a bonus episode here and there. But with the new school year very much upon us, I think we're ready to jump back in.Gretchen: Actually, here in California, school has already been going on for a few weeks. But that doesn't mean we couldn't use some tips on how to help our kids get off to a good start.Rachel: Not to mention what to do if things get bumpy fast.Gretchen: So to help us with that, we've invited back DeJunne' Clarke Jackson.Rachel: DeJunne' is a former teacher and school counselor based in Baton Rouge. Now, she works as an educational therapist and student advocate.Gretchen: She's also president of the Center for Literacy and Learning, a nonprofit that supports teachers who teach reading.Rachel: And she's a parent of two kids, one with learning differences and one without.Gretchen: Last time she joined us, we talked about how to prepare for parent-teacher conferences. And we will never forget her describing herself as "the five-inch binder mom."Rachel: We're so glad to have her back with us today. DeJunne', welcome back to "In It."DeJunne': Thank you for having me. So glad to be back.Gretchen: We are so happy to have you back. And last time we had you on the podcast, you talked about your two kids. And I know one of them learns and thinks differently and has an IEP. And I'm wondering if you're talking to your kids before school starts, and what kinds of conversations you're having with them.DeJunne': So, yes, I am having conversations with both my boys, age 9 and 14. So we're going into the fourth and the 10th grade. My oldest, of course, is the one with learning differences. So their conversations are the same, but different.And so we actually started having those conversations at the end of last school year. So we don't reserve those conversations for just the start of this upcoming school year. Mostly because my boys really try to avoid knowing that school is starting. So we — I really want to capture their attention when they're in this mindset of like being open to having those conversations about what the next school year looks like. What did this last school year look like?And my conversations with my 9-year-old look a lot different than my 14-year-old because his conversations are, you know, a lot around like social norms and expectations and, you know, our friendships in the social media realm and navigating teenager hood.Gretchen: Yeah, I'm so glad to hear you brought up social things. I'm wondering, especially with your older child, do you kind of reflect on last year in terms of academics and then set academic goals for the following year? Talk a little bit about that.DeJunne': Yeah. So we set academic goals for both kids. One thing about goal setting, though, our expectation is that both kids do their best. And it varies per subject. So we lean into the strengths.And if I know that science is your jam and you're good at it, then we set the expectation to match your ability. And if it's an A and we know you can perform at an A, then we set that expectation at an A. And if math is your challenge and we know you struggle through it and you show up every day to try your best and be your best, and if your best in math is a C on your best day, then a C is what we, you know, high-five you for.Rachel: I really like that — leaning into strengths and challenges. Because sometimes it can be easy for us to say, well, you got an A in science, so that means you can definitely get an A in math too, right? And then that can feel really defeating for your kid, because maybe they can't get an A in math too.DeJunne': And this is coming from an educator. So when I tell my friends this, they're like, Oh my God, I can't believe like, you don't want, you know, you don't want to to breed this like Harvard, you know?Even with my youngest, who, you know, who performs really well academically, and at the end of the day, I just want to create human beings that are, you know, wonderful law-abiding citizens, that are helpful, that have good hearts, and who are proud of themselves because they showed up every day and did their best.And so sometimes you just need to lean into those strengths. And then really appreciating and celebrating the strengths that are nonacademic, right? So having and appreciating the fact that your student may not excel. They may be a straight C student. But they're an extremely talented artist. Or they can play an instrument really well. Or they excel in sports.And that's the thing that keeps them going. That's the thing that helps them show up to math class every day that they hate. But they're doing it because the goal that you set is, you know, for them in order to get to that area of strength and to continue in that, you sort of tied in, you know, well, you know, we're going to make sure that we maintain our C average in all these subjects in order to support your love of art or go to this art showcase this year, you know. And so you just want to make sure it all marries together.Gretchen: Well, I'm going to switch gears a minute and get to a kind of more nuts-and-bolts question. A lot of times for many kids, the new school year also comes with like new organization methods. Maybe it's like a new folder. Or maybe they've gone to like the Dollar Store and gotten some caddies to organize things in. And it's going to be great. I'm going to be so organized with my pens here and this here.And then perhaps after a month or two, all this flash of new caddies and whatnot starts to fall apart. Do you have any strategies for this — of how to set like organization kind of goals that will actually work and won't break the bank too?DeJunne': Yeah, this — honestly, a very transparent moment as a parent. This has been one that we've struggled with. We had a laundry list of things that didn't work. We've tried binders and dividers and labeled folders and journals and agendas. And I think that's sort of where you begin. You try. And if it doesn't work, you try a different way. And you just keep trying something until it works.And we've, for a number of years, lived for a checklist. I mean, checklists got us through everything — from waking up in the morning, to tying our shoes, brushing our teeth, you know, taking our medicine, getting out the door. If we did not have a checklist, it did not get done.And that's one thing that we realized: Our kiddo was a minimalist. So the more things we gave him, the more frazzled he would be and trying to remember how to use those systems. Right? So that's why we we sort of came to the conclusion of, Oh, this is why a checklist was so easy, because it was simple.And so now we function with one notebook. We don't even have the fancy notebook with the divided sections. Because we tried that — like math, science, social studies. Everybody's getting written in one section. We do one folder and pray to God that all the papers get into the folder. Sometimes they are crumpled up at the bottom of the book bag most times. Rachel: But they're there.DeJunne': Yeah, but they're there. And then his computer and his phone are the most valuable assets for us, because his phone, the notes app — and of course I'm talking about the oldest kid with the learning challenges — the phone, his notes app. It's a running record of God knows what, but it gets there. And then his computer because his teachers in the communication, everything is on that computer. That's what we've sort of teetered along those lines.But yeah, we've struggled through a number of years because we wanted it to be all nice and pretty with the caddy and the different colored pens and the highlighters and stickers and, you know, and that works for some. And I say, go for it. And Dollar Tree will be your best friend, you know? But for some, less is more.Rachel: So for families with kids who learn and think differently, and maybe they have IEPs or 504s and maybe they don't. But they still want to kind of level-set at the beginning of the school year. Who should they touch base with? Teachers or school counselors? Specialists? And like, when is the right time to do that? Should they wait for their parent-teacher conference? Or, you know, how much time should they give for a conversation to happen that's just kind of like, hey, just want to touch base.DeJunne': Yeah. So I want to preface my answer by saying, yeah, there are categories of parents who have sort of been in this space of students with learning differences. I would probably be categorized as the crusader parent, right? I've been in this fight for a long time. I am probably the one that's on the horse with the shield, you know, with the sword in the air leading the calvary behind me.And so have to say that, right, because it depends on where you are in this journey. So I say that because my answer is everyone. Who you should touch base with is everyone at the start of the school year. Elementary looks much different than high school. Those "everyones" look a little different on each campus.But I also say that with — I use the sort of target or dartboard model when I work with the "everyone," you know, sort of model. I look at those who are closest or have the most touchpoints to my kiddo. So I may start with his classroom teacher. And of course, elementary, you'll know, it's probably just, you know, one teacher and maybe the school counselor. That's your core.But if your kiddo has an IEP, then of course the core is the IEP teacher of record. Then maybe your next ring could be the assistant principal or the dean or whomever. He may have a next touchpoint with your kiddo. Maybe your kiddo has some behavior challenges, so you may want to reach out to the dean of students or the vice principal who handles your behavior, you know, concerns. And then the next one might be the principal.But are sort of these layers, right, that you're building out from? But at the end of the day, I need everyone to know, hey, here's my kid. He has an IEP. I want to make sure you're aware and that you have a copy, and that he has those things in place on day one. And that I am his parent and that I am here to support you and to support him. And reinforce what is happening in the learning environment. And I want to do this outreach campaign at the beginning of the school year.To your point, I don't wait to parent-teacher conference. Because those usually aren't scheduled until like September, October, and by then it's too late. I don't want to talk about how he's underperforming at that time. I want to get it out and get it ahead of time.Gretchen: Right. Because your kids are starting in August. So October would feel like a long ways in.DeJunne': Forever away. So we want to get it ahead of time. Some send letters. I'm sure we've seen all the the letters that float around on social media that introduces their kid. I think those are so cute. I like the in-person, you know, feel so that we can put a face to name. I don't want to give too much information. I want them to get to know my kid for themselves, and just give them sort of that surface level of information. But just really as an introductory.Gretchen: Well, I know we're close to our end DeJunne'. But I do have a question that I think a lot of families might be wondering about, which is, you know, school starts fresh, start, you know, reset. Maybe a month in, oh my goodness. Things have not gone as we thought.Like maybe there's some, you know, bad interactions with other kids or teachers, you know, like my teacher, I don't like them. Or, you know, there's been a couple of failed tests or whatnot. Who knows what it is. But this you know, it's not the the glory you had hoped for. So how do you not despair? How do you not despair as a parent? And how do you help your kid not despair when that happens?DeJunne': It's difficult. You just you want — your immediate instinct as a parent is probably to fix it, right? You just want to fix it. You want to make it all better. I'd probably say that if things are looking doom-and-gloom in the beginning, that there's probably, you know, some transitioning pains, some growing pains.Because remember, this is new, especially your younger kiddos, new teachers. You're not doing it like Miss So-and-so did it. This is not how I'm used to it being done. It's new for them. That doesn't mean that it's necessarily bad. It's just different, you know? And so helping them understand the difference will really help as you talk to them through those things.I could probably say that there's probably a lack of communication or miscommunication or misunderstandings somewhere. I don't recommend just, you know, jumping in to trying to fix it. You know, have conversations for the goal of understanding and be proactive versus reactive. Really get into there and, you know, work with your child's teacher. Or work with whatever information that you need to know to be able to gain an understanding and awareness of what's going on. Instead of, you know, having them just adapt. Like, oh, get over it, you know, you'll get used to it.Encourage them to self-advocate. You know, it's so important and it's so underrated to have kids have a voice. And I think it comes from that, you know, that old-school parenting, that mindset that kids are, you know, to be seen and not heard. And I think we've done such a great job of trying to change that and have our kids be heard as we talk to our kids more and give them a voice. And have them know that it's OK to speak up.You know, teaching them, like, how do I politely interrupt. You know, even like sort of the process by which we speak up and that we use our voice. And so encouraging them to self-advocate. So if something doesn't sit right or feel right, or they believe that they are misheard or misunderstood, then how do I tell my teacher that? So even just giving them permission to have dialog with their teachers that they want just a better understanding? I think that that's a great place to start.Rachel: Yeah, and the teachers appreciate that. The teachers appreciate that.DeJunne': Yeah. Yeah. And they should. And if they don't, then that's a different conversation we can have.Rachel: Yeah, well, that is all so helpful. I have one more question. Any other advice you have for parents and caregivers or maybe even for teachers and support staff as we get settled into the new school year?DeJunne': Give grace. Our kids are trying. And if they're not trying, find out why. And I think when we get to that, we'll discover those strengths and pull out the things that they need help discovering. And I think we'll get our kids, you know, those goals that we set for them, they'll accomplish. I'm excited for our kiddos.Gretchen: I'm excited, too. Especially after talking to you today. I feel like it was a pep talk for us. Thank you so much for being with us, DeJunne'.Rachel: Thank you.DeJunne': Thank you for having me again.Gretchen: You've been listening to "In It" from the Understood Podcast Network.Rachel: This show is for you, so we want to make sure you're getting what you need. Email us at InIt@understood.org to share your thoughts. We love hearing from you.Gretchen: If you want to learn more about the topics we covered today, check out the show notes for this episode. We include more resources as well as links to anything we mentioned in the episode.Rachel: Understood.org is a resource dedicated to helping people who learn and think differently discover their potential and thrive. Learn more at understood.org/mission.Gretchen: "In It" is produced by Julie Subrin. Briana Berry is our production director. Justin D. Wright mixes the show. Mike Errico wrote our theme music.Rachel: For the Understood Podcast Network, Laura Key is our editorial director. Scott Cocchiere is our creative director. And Seth Melnick is our executive producer. Thanks for listening.Gretchen: And thanks for always being in it with us.

Back-to-school anxiety in kids: What to watch out for

Some kids get anxious over the start of school every year. That’s especially true for kids who struggle with learning or with making friends, and those with anxiety.Here are some things kids are likely to be anxious about as school starts this year:Being behind and not being able to catch upNot knowing their teacherNot fitting in with kids in their new classNot being prepared for changes or not knowing what to expectSchool safety Kids may need extra support as they head back to school. But families and educators can ease the transition and help kids manage anxiety.

In It

In ItExecutive function skills: What are they and how can we help kids build them?

Messy backpacks. Forgotten lunches. Missing assignments. How can we help our kids get organized this school year? Messy backpacks. Forgotten lunches. Missing assignments. How can we help our kids get organized this school year? What strategies can we use to support kids with ADHD and other learning differences? In this episode, hosts Amanda Morin and Gretchen Vierstra get back-to-school tips from Brendan Mahan, an executive function coach and host of the ADHD Essentials podcast. Brendan explains what executive function skills are — and how we can help kids build them. Learn why we might be asking too much of our kids sometimes, and how to reframe our thinking around these skills. Plus, get Brendan’s tips for helping kids get back into school routines. Related resourcesWhat is executive function? Trouble with executive function at different ages Understanding why kids struggle with organizationEpisode transcriptAmanda: From the Understood Podcast Network, this is "In It." On this podcast, we offer perspective, stories, and advice for and from people who have challenges with reading, math, focus, and other types of learning differences. We talk to parents, caregivers, teachers, experts, and sometimes even kids. I'm Amanda Morin.Gretchen: And I'm Gretchen Vierstra.Amanda: And this episode is for all those folks out there like me saying oh my gosh, oh my gosh, oh my gosh. How is it the start of a new school year already? How is summer over? And I don't know what I'm going to do because my kid doesn't know how to do school anymore.Gretchen: Yes, this transition can be especially stressful for parents of kids with ADHD and other learning differences. Maybe you had your systems down last year, like how to get your backpack organized or where your child does their homework after school. But will your child remember those things? And are those even the systems you need this year?Amanda: That's why we wanted to talk to Brendan Mahan. He's an ADHD and executive function coach. He's also got his own podcast, "ADHD Essentials."Gretchen: All right. Let's dive right in.Amanda: So Brendan, as an executive function coach, I would imagine that this start of the school year is a really busy time for you. What are you hearing from parents as they're facing down the beginning of a new school year?Brendan: It varies. Sometimes it's really specific. Like my kid struggled last year and I'm worried about how they're going to do it this year. Sometimes it's my kid's going into middle school, what do I do? Or my kid's going into high school, what do I do? Or I want my kid to get in a college and it's right around the corner — help. Like that. It's that sort of thing, right? But a lot of what I talk to parents about is like pump the brakes. Like, your kid is going to be OK. The school year hasn't even started that much yet.Amanda: OK. So I want to dig into all of that. But first, could you just explain what we're even referring to when we talk about executive function skills?Brendan: So executive function is the ability to do something, right? It's like the ability to execute. So planning and decision making, being able to correct errors and troubleshoot, being able to navigate it when things change and shift, when expectations are different and being able to handle that adjustment. It's understanding time and our relationship to it. It's sustained attention and task initiation. There's emotional control and self-awareness and self-understanding. It's kind of a broad category. There's a lot hiding underneath it.But it boils down to being able to do the thing. It's those adulting skills that, for one, we don't really expect kids to have yet anyway because it's developmental. But also we want them to have it before they're supposed to have it. And that causes its own sort of challenges.Gretchen: So I wonder, do kids tend to slide in executive function skills over the summer?Brendan: I don't know that they slide. I think the academic context of executive function slide. Sometimes we're still using some of those executive functions during the summer. Sometimes we're using more of some of them. You might have a kid who struggles to keep himself organized at school, right? But he's been playing with Legos all summer long and his Lego organizational skills are on point. And maybe that transfers to the classroom and maybe it doesn't.Summer is often when kids are much more self-directed. They're much more curious and exploratory. There's more space for that. So that stuff is going to grow when it may have slid during the school year, because they didn't get the opportunities that they might get during the summer.Amanda: I'm going to go back to something you said, though, because it piqued my curiosity. We expect kids to have executive function skills before they're developmentally ready for it. Why do we do that? Or how do we stop doing that? Or what should we be doing instead?Brendan: I'll go for all of it. Like, how big of a jerk do you want me to be?Amanda: Realistic. Let's go with realistic.Brendan: The answer to that, and this is me being a jerk, is kids not having executive functioning skills is inconvenient.Gretchen: Right.Brendan: Right? Like it makes our lives harder that they can't follow 10-step directions.Gretchen: Brendan, can you give a kind of a general overview of what skills I should expect of typical kids in like grade school and up? So I'm not asking for things I shouldn't get.Brendan: So breaking it down into, like, elementary school, middle school, and high school. It's at least academically how we break things down. So we should expect elementary school kids to be able to pay attention. But there's high school kids who have trouble with that, right? So like, that's kind of an illustration on executive functioning challenges. But broadly speaking, we're expecting elementary school kids to pay attention, control their behavior and impulses, follow one- to two-step directions, and be able to change their behavior to follow rules as necessary.Amanda: The kindergarten teacher in me is going to pop in here and say, "pay attention" is a really like nebulous one, right? Because when I was teaching kindergarten, it was like, pay attention for 10 minutes was about as much as they could could do, right? So I just want to caveat and say, yes, pay attention. I also think about how old the kid in front of you is, for how long they can pay attention.Brendan: True. And absolutely like 10 minutes for a kindergarten kid, and sort of add a few minutes per grade level kind of thing. But also, what does "pay attention" mean? Right? I'm really glad you called that out. Because for some teachers, "pay attention" means sitting with their back against the back of the chair and their legs against the bottom of the chair and their hands folded on their desk and looking at the teacher and — and like, I did that in school. And I did not know what was going on. Because my imagination is way cooler than anything my teacher had to say.Amanda: It may be time to narrate for our listeners that Brendan is standing up as he records, and I'm sitting a swivel chair and swiveling back and forth. Yet we are still paying attention.Gretchen: We're paying attention. So then what about middle schoolers that I know Amanda and I have.Brendan: And I do, too. Yeah. For the middle school kids, we want them to start to show that they can think in order to plan an action. We want them to be able to plan ahead to solve problems, even. Right? Like this is a problem that I might encounter when I do my social studies project or whatever. We want them to be able to follow and manage a daily routine. So an elementary school kid not knowing where they're going on a given day? We might not worry about that too much. Middle school kids, we start to go, oh, wait a minute, you should know what's happening. I want to caveat this, though, because some middle school schedules are a nightmare.Gretchen: A day, B day, short day.Brendan: Yeah. We also for middle school kids, we want to see them beginning to develop this skill of being able to modify their behavior across changing environments. Do we expect to see this because it's developmentally appropriate? Or do we expect to see this because that's how middle school works and it's necessary that they can? I don't know.Gretchen: It makes me think I'm asking too much.Amanda: Makes me think I'm asking too much, too.Brendan: Yeah. One of the things that I often talk about with my clients, with my coaching groups, is when a kid is struggling, we want to wonder: Is it the fish or is it the water? Right? Like, is this kid struggling because there's something going on with them? Or is it the kid's struggling because there's something going on with the environment that they're in? Probably it's both. And oftentimes we focus on the fish instead of looking at the water. So I tend to champion like, let's address the environment that the kid's in.Amanda: As a parent staring down the school year, what do I do right now to start bolstering those skills?Brendan: So if school hasn't started yet, I might be talking about things we can do during the summer to kind of get ourselves squared away so that the beginning of school goes more smoothly, right? Start going to bed a little bit earlier now, so that when school starts and you have to go to bed a lot earlier, you can make that transition more effectively. Or give your kids like a few more responsibilities for the time being, so that when school starts, you can take those extra responsibilities away and replace them with the school responsibilities that are coming. Which doesn't mean they should be writing essays at home. It just means that they should be doing a little bit more in terms of chores or something, so that they're used to not being as relaxed and on as much screen time as they were in the summer.And if school is already started, then it's like trust the teacher, right? Like let's communicate with the teacher. Let's find out what it is that they're doing in their classroom. Are they seeing challenges or red flags already for your kid, or maybe orange flags? Is there anything we need to be on top of right now? So don't wait until the problem happens, like solve the problem in advance instead of solving it after things have gone haywire. And pivoting really quick, because one thing I didn't do is I didn't talk about high school.Gretchen: Oh, yeah. High schools.Brendan: So emerging skills in high school: We expect them to start to be able to think and behave flexibly. We also want to see them begin to organize and plan projects and social activities. Now, social activities, yes. But like, why do they have to be able to organize and plan projects? Because that's how high school works, right? And that skill has been building since middle school, maybe even since late elementary school. But now we're starting to expect more independence and it should be an easier process.We also want to see them adapt to inconsistent rules. And it happens in lots of ways, right? Like I just left English class and now I'm in math class and I can't shut up because I was talking a lot in English and it was fine because we were doing group projects and now it's a solo thing in math, right? That's hard. But we start to expect that. Yeah, you have like three-minute hallway time and then you got to be ready to go behaving totally different for a new subject.Gretchen: That three-minute time is like, I've got to say, as a teacher, even I had trouble switching, right? You're going from one class to the next and there's no downtime to readjust. That's tough.Brendan: Yeah, but that's time on learning, right? That's like you've got to be learning, learning, learning. Which is silly, because we know we need time for our minds to wander in order to cement that learning and sort of lock it in. And if we don't give kids any time that's downtime to have their minds wander and be a little spacey, they're not going to be able to anchor in that learning as effectively as they might otherwise.Amanda: Well, I will say that as a parent of kids who have ADHD, I have often been the parent who was like, you don't have to go do your homework right away. And I know that that's sort of antithetical to like all what a lot of people say. You know, come home from school, do your homework, get it done, then do your other stuff. But my kids weren't ready to. They needed that time to sort of breathe or let their brains breathe or whatever they needed to do. We can have the homework station all put together, but it doesn't mean we have to put the kid at the homework station the minute they walk in the door.Gretchen: Right.Brendan: Right. And how much of that is coming from your own anxiety?Gretchen: Just get it done, man. Go to that seat and do it, right?Amanda: OK, so what's the conversation sound like if I am trying to get my kid in the game, get their head in the game, and not put my anxiety on them? What's that conversation sound like?Brendan: A lot of that conversation is happening inside of you and doesn't need to be shared with them, right? Like, because you got to work on your own stuff before you can have this conversation. You have to figure out what is it about, in this case, homework, and doing it as soon as I get home, or is having my kid do it as soon as they get home. What is it about that that makes it so important to me? It might be that transitions with your kid are wicked hard and you don't want to have another transition. You don't want to have to battle them to come and do homework at 5:00. So it's easier to avoid that battle because they're kind of still in school academic mode. So you can at least get them into it better.And that might be because you're doing it wrong in terms of what activities you're having them do before they do homework. Screen time is not a plan before homework, unless you know you can trust your kid to pull out of that screen and go into homework. If there's ever a battle around getting out of screen time, then they need to do something else before they do their homework.Gretchen: Yeah. That brings me to a related question, Brendan, which is sometimes kids have it together executive function wise, especially when they love something, right? But when they don't like something, all of a sudden I see the skills go away. And I wonder, OK, are they struggling or is it that they're just choosing to not have those skills in that moment because they don't want that for that thing?Brendan: When we're talking about kids, it is never useful to decide that they're choosing to not do or do anything. Because all that does is vilify the kid and make us, as parents, feel more justified in being meaner to them. Instead, we always want to assume that our kid is doing the best they can. And we always want to assume that they are trying to do well and want to please us. Those are my fundamental assumptions at all times. And have I screwed up? Yes. There was a period of time when my kid was struggling, like a lot of kids right now. Post-COVID, there's a lot of anxiety stuff going on with kids.My kid is one of them, man. And I was wrapped up in my own anxiety as a result of his anxiety, and I wasn't thinking as clearly. And we started battling. And we had one particular rough battle that my wife got caught in and I sat down on a bed. I can still see it. I can see myself sitting on the bed and going, I'm doing it wrong. Like we should not be battling. This is not the relationship I've had with my kid for the last 13 years. What am I doing wrong?And I literally went through in my head the slides of the parent groups that I run. And I hit this one slide that is like everyone is doing the best they can. Your kids want to please you. They want to succeed. And if those things don't feel true, it's because there's a skill set that's missing or there's a resource that they don't have that they need. And I was like, he's doing his best, and his best is not up to my standards. And that's because something else is going on. I knew what that something else was. It was the anxiety stuff that's going on. And I was just like, oh, the skill set that he's missing is the anxiety management skills that he needs.But it wasn't that he couldn't do the stuff that I want him to do. It was that he couldn't manage his anxiety. And the only reason I started banging heads with him was because I was so anxious that I couldn't bring the skills that I usually have to bear to navigate the challenges that he was facing and help him out. So it makes sense. It happened to both of us at the same time, and that's why we were banging heads. And our relationship changed from that day forward.Amanda: I'm going to push, though, a little bit, because I really I'm super curious about the kids who say to us, like, I'm just not feeling it. Like, is there something below that, you think?Brendan: What's below when you're not feeling it? Like there's times when we're not feeling it either, right? And there's something below that, too. Sometimes it's I haven't slept well for a week, and I'm just done. I don't have the mental capacity to do this. Sometimes it's I haven't moved my body in like a month and a half and that's affecting my get-up-and-go. Sometimes it's I'm chock-full of anxiety because someone in my house has a chronic illness or I'm afraid of COVID or or my parents are getting divorced or whatever, right?There's all kinds of reasons why kids might not feel it. And if they say, I'm just not feeling it, there's two really good responses. One is cool, then you don't have to do it. Like figure out when you can. Give me an idea when you might be able to do this, and we'll do it then. The other answer is, I totally hear you that you're not feeling it and I get it. I can tell that you're not feeling it, but unfortunately you still got to do it. How can I help you get this done?Gretchen: I like that language.You brought up not wanting to battle your child and none of us want to battle our child. But in thinking about going back to school, we might be getting feelings from last year of oh my gosh, the backpack was so disorganized. Oh my gosh, why didn't you bring home your homework assignments? So how can we start off the year better, but get some of those basic skills under control?Brendan: So I have some videos on "How to ADHD," Jessica McCabe's YouTube channel, on my Wall of Awful model. That is exactly what we're talking about right now. The idea behind the Wall of Awful is that — I'll do like a two-second thing. Watch the video. It's like 14 minutes of your life. The gist of the Wall of Awful is that, like, we have certain stuff that we do that we fail at or struggle with. And as a result, we get these negative emotions built up around that task. And we have to navigate those negative emotions before we can do the thing.So if we've battled with our kid about school a lot, as school comes back up, we have a Wall of Awful for navigating school as much as they do. So we get in a fight and argue about stuff. Just put your shoes on, or whatever. And sometimes it's that petty, right? Like we're yelling at our kid to put their shoes on, even though they have 10 minutes before they even have to get on the bus. And it's not about the shoes. It's about all of the battles we've had about school for the last seven years or whatever.So to get ahead of that, talk to your kids before school starts about how you have conflict when school starts. And ask them, like, what do you notice about this conflict? What do you need for me to help avoid this conflict? Or this is what I need from you to help avoid this conflict. What do you need from me to help give me what I need, right?Because that's what parenting boils down to. Parenting boils down to what does my kid need from me in order to be better? So whenever I have a conflict with my kid or my kid is struggling, I'm always asking them, like, what do you need from me? And sometimes what they need from me is for me to intentionally give them nothing so that they can figure it out on their own. Sometimes that's what I'm giving, is like independence.But if that doesn't work, I need to be ready, like a safety net with, like, other stuff, right? Like, oh, you also need me to, like, bust out a timer and remind you that those are useful. Or break this task into smaller, more manageable chunks. Or, as I had to do for one of my kids recently, text the dad of one of their friends that he wanted to hang out with, because he just didn't have it in him to text his friend. And we had that conversation. I was like, cool, then I'll text the dad. Not a big deal.Amanda: Sometimes my kid doesn't know. My kid's like I don't know what I need from you. So as parents, having those examples of what you can then say: Is it this? Is it this? Is it this? What else would you add to that list?Brendan: First I would add if the kid says "I don't know," say to them, "You don't need to know. I don't want the answer to this question right now. I can, like, take a few hours, take a day." Because when we put a kid on the spot, anxiety spikes, executive functions shut down. They don't know. But if we give them some thinking time and some grace, then they can come back later and tell us stuff. Or maybe not. Maybe they come back an hour later and they're like, I still have no idea.Then we start giving them examples — examples that are informed by what we already know about our kid. Do you need me to get some timers? Do you want to sit down with me and I can body-double you while you work on this? I got some knitting to do, or I have to pay the bills. Like we can sit at the kitchen table, you can work on your thing, I can work on my thing. Do you want help breaking this down into small, manageable chunks? I know sometimes you struggle with that a little bit. Would it be useful to maybe call up Sally and have Sally come over or do a Zoom with you and you guys can work on this together? Would that be helpful? Like, and something else that you thought of, because I am running out of ideas? Like, what do you think?Amanda: So we're all about executive functioning today, which always includes time management. And Brendan, I know you said you had somewhere to be. So I just want to thank you so much for sharing all of these insights and advice with us today.Gretchen: Yes, thank you so much, Brendan. So much for us to think about.Brendan: Thank you for having me.Gretchen: Brendan has lots more to share with families who are working on building their executive function skills. Go to ADHDEssentials.com. That's where you can also find his "ADHD Essentials" podcast.Amanda: You've been listening to "In It" from the Understood Podcast Network.Gretchen: This show is for you. So we want to make sure you're getting what you need. Email us at init@understood.org to share your thoughts. We love hearing from you.Amanda: If you want to learn more about the topics we covered today, check out the show notes for this episode. We include resources as well as links to anything we mentioned in the episode.Gretchen: Understood.org is a resource dedicated to helping people who learn and think differently discover their potential and thrive. Learn more at Understood.org/mission.Amanda: "In It" is produced by Julie Subrin. Briana Berry is our production director. Justin D. Wright mixes the show. Mike Errico wrote our theme music. For the Understood Podcast Network, Laura Key is our editorial director, Scott Cocchiere is our creative director, and Seth Melnick is our executive producer.Gretchen: Thanks for listening and for always being in it with us.

Back-to-school concerns about your child: How to act on them

Back-to-school is anything but ordinary this year. You and your child might feel anxious about the return to school — whether it’s in-person, remote, or a combination of the two. That’s especially true if your child is struggling with learning or behavior. In this series, we talk about the concerns many families are coping with, and how to work with your child’s teacher to get ready for back-to-school this year.

In It

In ItWhat if the teacher has learning differences, too?

Teacher Kara Ball shares what school was like for her as a student with dyslexia and dyscalculia, and how that experience shapes her work today.We all know that an amazing teacher can have a huge impact on our kids. But is that impact even greater when that teacher learns and thinks differently, too?In this episode, hosts Amanda Morin and Gretchen Vierstra talk with Kara Ball, a teacher who’s “in it.” Kara shares what school was like for her as a student with dyslexia and dyscalculia, and how her interactions with teachers shaped her experience as a student. Listen in as we learn more about how Kara’s learning differences impact why and how she teaches — and especially how she engages with her students.Related resourcesWhat is dyslexia?What is dyscalculia? Understanding IEPsEpisode transcriptAmanda: Hi, I'm Amanda Morin. I'm the director of thought leadership for Understood.org. And I'm also a parent to kids who learn differently. And this is "In It." "In It" is a podcast from the Understood Podcast Network. On the show, we talk to parents, caregivers, teachers, experts, and sometimes even kids. We're going to offer perspective advice, stories for, from, and by people who have challenges with reading, focus, and other learning differences. And I am so excited to be joined by my co-host, Gretchen Vierstra. Gretchen, want to introduce yourself?Gretchen: Sure. Hi everyone. I'm Gretchen, and I work at Understood with Amanda as an editor, and I'm a former classroom teacher. And gosh, when I was teaching, I wish I had known everything I know now from Understood. I'm also a mom of two, and Amanda and I talk about our kids all the time. So I'm happy to be doing this podcast with you, Amanda. Amanda: I am so excited you're doing this with me, Gretchen. And I'm really excited about this first episode of the season.Gretchen: Amanda and I have been thinking a lot about what a big transition this is right now for so many kids and parents heading back to school — like a real physical building — after a year or more of being remote.Amanda: I mean, on the one hand, let's be real. Many of us are so excited to get our kids out of the house. But on the other hand, over the past months, we may have learned things we didn't know about our kids as students, and may be a little worried that our kids' teachers aren't going to get them.Gretchen: That's why I wanted to talk to Kara Ball. Kara is an elementary school teacher in Maryland. She's a science and stem education specialist. And in 2018, she was a National Teacher of the Year finalist.Amanda: We wanted to talk to Kara not only because she's a great teacher, but also because she's someone who learns and thinks differently. She has both dyslexia and dyscalculia, which can make number-related tasks difficult. And she brings that perspective into the classroom in such a beautiful way. Gretchen: We started by asking her why she wanted to become a teacher.Kara: Yeah. So I am one of the few people that has always known that they've wanted to be a teacher. The first recollection I have of that is in the basement of my childhood home, my grandmother, who was a teacher, I gave me one of those classroom-in-a-kit boxes, where it would come with the chalkboard and the stickers and a red pen — basically everything you needed to be a teacher.And I would spend every summer in the basement of my childhood home, hoarding all of the handouts and worksheets that my teachers would give us to use in my classroom where my students — a class of three: my baby sister, baby brother, and my father who was by far, the most challenging student I've ever had as a teacher — would learn all about the things I learned in school. And I absolutely loved that classroom, but had a very difficult time being a student in the classrooms in the schools I attended. I wasn't diagnosed until third grade with dyslexia, and I made it all the way to sixth grade before I was identified as having dyscalculia. So reading was really challenging. Math was really challenging. School as a whole just seemed impossible. And when I was growing up, special education services were very much something you did in the, like, the classroom in the back of the building, out of sight, out of mind. And my dad who was also dyslexic, did not want me to experience that type of education.And I am lucky enough to have a grandmother who was a teacher, a dad who also identified like myself as someone being dyslexic, who advocated on my behalf to be able to have an inclusion model of education in which I received the services in the classroom, but were pulled out to be able to get the supports that I needed, which was kind of unheard of at the time. I mean, this was the late eighties, early nineties that I was in school. But even with those advocates, it didn't change that I went through the day to day, the school day, trying to — I remember choral reading where you would get a book and you would have to like read out loud of a certain passage. I would spend my entire like period not listening or comprehending everything else that was being read, trying to figure out how to read my little paragraph before they got to me, because I knew that I was going to stumble. I was going to make a mistake. And it was so stress-inducing that I would, I was the kid that asked for a bathroom pass. Anytime we had to read anything, I lied. I was like, I gotta go. Like I just had to get out, because I didn't want anybody to know how difficult it was for me just to keep up.Gretchen: First of all, that story is incredible. Going all the way back to when you were in the basement with that little red kit — I know that red kit, my kids play with that red kit, I think. At least they used to, not anymore. Can you tell us a little bit about how you got diagnosed? And when that happened how that felt for you?Kara: Yeah. So it was Miss Liddy. I have photographic memory, so I pretty much was able to memorize all of the books that we had in our classroom library. So no one caught it, up until third grade, that I couldn't read. My parents read to me. We had books at home. We went to the public library. It was just that it was twice as hard for me to learn how to read, to hold on to words.And she was the first teacher that started doing those small guided reading groups with me, and bringing in books that I didn't have access to in the classroom library that I couldn't listen to a peer read to me and then memorize it before I was assessed on it.Gretchen: So your cover was blown, right? Kara: Exactly. My cover was blown and she was like, "Hey, this might be why, you know, her writing and her print. And this might be why she inverses, you know, her speech sometimes." Like she knew. Amanda: Those moments where a teacher intervenes are so important. And it takes someone like Miss Liddy, who's really paying attention, who's picking up cues and not making assumptions about why a student is or isn't performing well. You know, and it reminds me of when Benjamin, my son, had a chance to talk to Kara about this on a webinar they did. He talked to her about his fourth-grade teacher, Mr. Sloteman, who realized that Benjamin actually paid attention better when he was doodling at the same time as listening. And then what Benjamin thought was so cool is that Mr. Sloteman made sure all the other teachers knew too, so that they could get a better understanding of Benjamin.Gretchen: I love hearing stories like that. I love it when a teacher really notices something about a student and pivots and makes that difference. And in fact, that happened for Kara a lot. She had some great teachers who really impacted her learning in a positive way. But there were also some cases where she had some negative interactions.Kara: For most of my, you know, K through 12 years, I felt like I was the dumbest person ever. As bad as that word is, that was the word that I would have chose because it's what I heard. It's what people said to me or about me, even teachers who, you know, thought I couldn't hear what they were saying because they were, you know, two feet that way, would talk about me in terms of all the things that I couldn't do rather than what I could do.When I hit ninth grade, I encountered a science teacher who would ultimately be the reason I became a STEM education teacher. And Mr. Dalton was somebody who, for whatever reason, looked at me as a less than C average student with an IEP and said, let's give her a shot. And he enrolled me in my first ever honors science class.And I still talk to Mr. Dalton today. He was the second person I told when I was named State Teacher of the Year. Because up until that moment in time, I thought that I wasn't a good student. And it was really interesting because it high school, I managed to have this amazing experience with Mr. Dalton, who got me into science, while simultaneously had my 10th-grade math teacher tell me in front of the class that I was stupid and never going to amount to anything. It still hurts my heart today when I think of how I felt in that moment. I left the class. I was never a rule breaker. I never walked out. I walked out of that classroom. But I walked out of that classroom and I walked to Mr. Dalton's classroom, because I had a safe space. I had a teacher who knew of me beyond what I showed on paper. And if I didn't have the Mr. Dalton, if I didn't have my grandma, if I didn't have my parents, that could have been the day I dropped out.I was a 10th-grade student that didn't have great grades, didn't think I was going to go to college, and had this basement dream of becoming a teacher. But everybody else but one person was saying it wasn't possible. And I didn't. I didn't drop out.Gretchen: Kara, when you were diagnosed then, did that change your perspective on learning? Kara: So it didn't. Like I knew the label. I never really saw the IEP paperwork as a child. I wasn't really in those meetings. I just kind of either had a calculator or didn't have a calculator. I either got to go in a private room or didn't go in a private room.And that's one of the things I work with my students on: understanding why they have these resources and how to be an advocate for themselves. Because a lot of people aren't going to just do it for you. You really have to know how to do it for yourself. And it's that conversation that shifted me to being more willing to talk about it. Because one of the biggest problems I have is that I know my students that have IEPs. I know my students have learning and thinking differences. But I don't hear about them as adults. They don't disappear. Like I'm not magically not dyslexic because I'm 19 and aged out of public school. What happens to you when you're an adult, and being able to show that you can have an IEP, you can be a successful, accomplished adult, you can go to college, is something that's not talked about. And I'm honest with my students, especially my older ones that, you know, it's not always going to go over well. Some conversations are going to have pushback. Like I've had employers where I've had to be like, "don't make me call a lawyer in" type of conversation. Like "I am entitled. I know my rights." But it's taken years of practice to get to that point, to stand up and be able to be an advocate for myself. Cause like, I don't have my parents in the corner. I mean, I could, I could call my mom at any moment and she'd be like, "I'm coming. Let me get the binder." I got years of documentation. But, like, I needed to be able to do that on my own. And it's because of the support systems that I have. And I'm hoping that I'm doing that for my students now.Gretchen: Speaking of families and parents — which by the way, I want to meet your mother with the binder, that sounds amazing — I'm wondering what advice do you have for families who are, you know, they're coming across this with their child for the first time. How can they talk to their teachers? How can they talk to their own child about this? Kara: So my advice to parents always usually starts with educating themselves. That's the first thing, is know your rights. I would love to say that all school systems are gonna follow the law, but that's not always the case. So it really needs to be on them to know their rights and what they're entitled to. And you get the little document at your first initial IEP meeting. Hold on to that. Read it. Do the research.Amanda: Then go to Understood to look at it because it's broken down better at Understood. The document that they give you is totally overwhelming.Kara: It is like you're in law school and are supposed to understand all of this.Amanda: Totally inadvertent plug there. It was just a matter of me thinking like what that document looks like and thinking how overwhelming it is to me. I have a degree in education. I'm a trained special education advocate. And I'm still panicking when they hand me that piece of paper.Kara: And then I would always say to approach any conversation you had with your child through the lens of empathy and compassion. Because you might not understand. Like now there are lots of groups on the internet you could connect with, find other people who might be having similar experiences. It's nice to be able to have a platform where you can share your frustrations, but at the same time, get help and support and something that is unique to you and your family.Gretchen: I'm just curious: Why STEM education? Because you know, for me, for example, growing up in school, math was not my strong suit or science, so I became an English teacher. So what drove you to STEM?Kara: I have always been that curious kid. I want to know everything about everything. And if I don't know, I need to look it up right away. My dad has a degree in biology, and when he saw the things that I was having a hard time with, rather than, you know, telling me to come and sit down and let's work through this textbook, we went out and we did it. So when I didn't understand geometry, we built a two-story treehouse. When I wasn't understanding force and motion, we went out and we made model rockets. We made pinewood derby cars. I was the first female participant in my brother’s pinewood derby for the Boy Scouts troop, and I won. Gretchen: Nice.Kara: But I do a fifth-grade pinewood derby unit with my students. I do a fourth-grade model rocket unit with my students. We design bridges. We do computer science. We do robotics. It's living through the learning as the thing that I really liked. And I also valued and appreciated that failure was celebrated and recognized as a natural part of the learning process, where in other practices and academic areas, with the exception of writing, we don't see that. In writing, you go through edits and drafts. And STEM, you go through iterations and revisions. But in math, you just have to fix it.Gretchen: Yeah. I hear what you're saying, right? The engineering, like the design engineering process, lends itself to this inquisitive trying out things, seeing if there's a new angle to do it. Not always having to stick to the same way of doing something and learning from mistakes. Kara: Yeah. The resiliency and perseverance that you have to learn through STEM education is something that I have always found my students who learn and think differently are better at than my students who have things that come pretty naturally and easy to them. They have the ability and the willingness to persist and to struggle and to productively struggle through things more so than some of their other peers. And all of a sudden, things that would seem so negative become a positive. They're like, oh yeah, I can do this. Like, let's go, let's try it again, try it again, try it again.Gretchen: You know, Kara made a really important point back there about how sometimes we forget that kids with learning differences grow up to be adults with learning differences. Right?Amanda: They don't just disappear. Although hopefully we help those kids develop the skills they need, so they know how to navigate those differences when they grow up.Gretchen: Kara told us a great story about what it's like being a grownup with dyslexia and dyscalculia.Kara: I had a really unique interaction a couple of years ago at a yard sale, which was a fully teachable moment. But I think one of the hard things is that my learning and thinking differences aren't visible to many people and they make a lot of assumptions, even as an adult.I was at a yard sale when somebody was buying something from my mom's table, and I was making change for them. But I used my calculator because I wanted to make sure that I gave the right amount back. And they just passively said, oh, you know, they don't teach math to these kids everyday. First off, I was older than they were. Second off, I was like, first, let me tell you a little bit about myself. So I have dyscalculia. I can't hold on to numbers or digits. I can't make change in my head. I still use my fingers to count if I don't have a piece of paper to solve it out. I have to put this in there because I just can't do it. It's not that I don't understand the sequence, the steps, the process, or the actual, like, you know, how to do the math problem. I just physically can't hold on to digits in my head. And they were actually very receptive to that conversation. They had never heard about that, and they had never taken it into consideration. But that is something I never would have done as a child growing up. I never talked to people publicly about it unless I had to in order to get ADA accommodations. If I had to, because I was going to enroll into a class and I needed my professor to know, but it was a private, behind closed doors. I didn't want to stand out or be seen as being any different than the rest of my peers.When I was named State Teacher of the Year, I had to discuss it with the people that I was working with. And they were like, why don't you talk about this? Like, this is really important. And I talked to my students about it, but I never talked to other adults about it. Because there's still that stigma of shame and embarrassment and not really understanding how to talk to people about it.Amanda: What do you say to your students?Kara: So I usually tell them, I say, oh, you know, it's really hard for me to learn how to pronounce words or, it's not that I'm bad at math. It’s that sometimes math is hard for me, but here is what I do. So like I got switched from fourth grade to fifth grade one year and they were doing partial quotient, and I needed to learn how to do that. And rather than learning, like after hours or during my planning, I told the students that I don't know how to do this. I want to learn with you. So I got myself a textbook and I learned right alongside my students. We went through the problems. I had a couple students that were more proficient at it than I was. And I said, this floor is yours. Like, you tell us how we should do this. Amanda: I have one last question for you. I'm going to ask you the tricky one. What would you say to the math teacher whose class you walked out of? What would you say to him today?Kara: So I actually got the opportunity to sit down with them. It's that I wanted to be the student that he wanted me to be. I don't want to have these problems. I don't want to have to work twice as hard. I was in your remedial math class and afterschool tutoring, like I'm not here because this is fun. And I just wish that he knew that I really wanted to be the student that he wanted me to be. But here we are. Amanda: Here we are. You amounted to a lot, and we are so glad that you came and spoke with us.Gretchen: And thank you for all of your honesty, Kara, and just for sharing your story in a fun way that other folks can relate to. Thank you so much.Kara: Anytime. Thank you so much for having me.Amanda: You've been listening to "In It," part of the Understood PodcastNetwork. Gretchen: You can listen and subscribe to "In It" wherever you get your podcasts.Amanda: And if you like what you heard today, please tell somebody about it.Gretchen: Share it with the parents you know. Amanda: Share it with somebody else who might have a child who learns differently.Gretchen: Or just send a link to your child's teacher. Amanda: "In It" is for you. So we want to make sure that you're getting what you need. Gretchen: Go to u.org/init it to share your thoughts and also to find resources from every episode.Amanda: That's the letter U, as in Understood, dot O R G slash in it.Gretchen: As a nonprofit and social impact organization, Understood relies on the help of listeners like you to create podcasts like this one to reach and support more people in more places. We have an ambitious mission to shape the world for difference, and we welcome you to join us in achieving our goals. Learn more at understood.org/mission.Amanda: “In It” is produced by Julie Subrin. Justin Wright mixes the show. Mike Errico wrote our theme music. Laura Key is our editorial director at Understood.Scott Cocchiere is our creative director, and Seth Melnick and Briana Berry our production directors. Thanks for listening, everyone. And thanks for always being in it with us.

Back-to-school making you and your child anxious? These strategies can help

Q. My child always feels anxious when it’s time to go back to school — and so do I. How do I help us both calm down? A. Back-to-school anxiety is common for both kids and parents, especially when school is a struggle. Some kids feel anxious about going back to school because of their experiences from the year before. (Parents can feel that way, too.) Some kids have social anxiety. They may worry about having a new teacher — or even about new kids in the class. And some kids feel anxious about having to sit still in class. It’s also common for kids to have “jitters” or feel nervous about beginning something new. They may be thinking about what could happen in the new school year. These feelings are often temporary. But in the meantime, they can affect the whole family. Parents can help by validating feelings and offering perspective. For example, “I know last year was hard. I can understand why you’re feeling nervous. But this is a new year and a new teacher. And we’re here to support you.” Parents may feel nervous about school starting again, too. If you’re feeling a bit anxious, take a moment to think about your own time in school. Think about your interactions with teachers and peers. Take note of your thoughts and feelings. Then think about the positive outcomes the new school year can bring. This will help you to lead by example when helping your child express their own thoughts and feelings. If you find your anxiety is hard to manage on your own, consider talking to a friend or a counselor. Planning ahead can also make it easier to feel less anxious. See if you can chat with your child’s teacher before the school year begins. Ask how you can work together to provide support in the classroom. If your child has an IEP or 504 plan, make sure it’s up to date. You and all your child’s teachers should have copies.Finally, make going back to school a pleasant, positive event. Plan a big first-day breakfast. Talk about all the things your child is excited about, like seeing old friends, or getting to join a club they’re interested in. And, above all, let your child know that you’ll be there for them, every step of the way. Anxiety that doesn’t go away or that makes it hard for someone to function could be a sign of something more serious. For example, a child might become so anxious that they have trouble going to school at all. Or a child may not be able to stop thinking about a negative experience from last year. If you notice that your child’s anxiety seems overwhelming, consider getting help from a professional.Get tips on how to manage your child’s back-to-school anxiety.Download this plan to help your child start the new school year right. Learn five things you shouldn’t say to kids about the new school year.

In It

In ItCan we talk? Omicron, school, and our parenting fears