123 results for: "autismo"

Is autism a learning disability?

See two grade-schoolers explain what autism and dyslexia feel like in this video from Not Your Mum.

Understood Explica el IEP

Understood Explica el IEPEl IEP: ¿Mi hijo necesita un IEP?

Obtenga recomendaciones de una maestra de educación especial sobre cómo saber si su hijo necesita un programa de educación individualizado (IEP) o si podría esperar. Si su hijo está teniendo dificultades en la escuela, es posible que usted se pregunte si podría necesitar educación especial. Y una vez que comience a averiguar sobre la educación especial, escuchará el término IEP, que son las siglas de “Individualized Education Program” (Programa de Educación Individualizado).Pero ¿qué es exactamente un IEP? En este episodio de Understood Explica, la presentadora Juliana Urtubey explicará los aspectos básicos del IEP y cómo averiguar si su hijo necesita este tipo de apoyo. Marcas de tiempo:[01:24] ¿Cuál es el propósito de un IEP?[04:53] ¿Qué es un IEP? [07:57] ¿Necesita mi hijo un IEP? [10:42] ¿Debería esperar para obtener un IEP para mi hijo? [13:54] ¿Y si mi hijo está aprendiendo inglés?[16:04] Puntos clavesRecursos relacionadosEntender el IEP¿Qué es una evaluación de educación especial?¿Son las dificultades de mi hijo lo suficientemente severas como para una evaluación?Estudiantes de inglés con dificultades en la escuela: Lo que necesita saberPreguntas comunes de los padres que no conocen el sistema educativoTranscripción del episodioJuliana: ¿Así que su hijo está teniendo ciertas dificultades en la escuela y usted se está preguntando si necesita un IEP? Pero ¿qué significa esto? En este episodio de “Understood Explica", brindaremos información básica sobre el IEP y cómo saber si su hijo necesita este tipo de apoyo. Desde la red de pódcast de Understood, esto es "Understood Explica el IEP”. Hoy vamos a responder la primera pregunta relacionada con el proceso del IEP. ¿Mi hijo necesita un IEP? Mi nombre es Juliana Urtubey y soy maestra certificada a nivel nacional y experta en educación especial para estudiantes multilingües. En 2021 fui seleccionada Maestra Nacional del año y estoy muy emocionada de ser la presentadora de la tercera temporada de "Understood Explica". Les cuento brevemente cómo estamos estructurando esta temporada. La mayoría de los episodios se centran en información sobre el IEP que es importante que conozcan todos los padres y cuidadores. Pero también algunos episodios están dirigidos a diferentes grupos de familias. Familias con niños pequeños, con niños mayores y con estudiantes multilingües. Y todos los episodios están disponibles en inglés y en español. Bueno, entonces comencemos. [01:24] ¿Cuál es el propósito de un IEP?Entonces, ¿cuál es el propósito de un IEP? Antes de responder esta pregunta, me gustaría explicar rápidamente qué es un IEP. IEP es la sigla en inglés de Programa de Educación Individualizado. Se trata de un plan formal que describe los apoyos y los servicios que necesita un estudiante con una discapacidad para progresar en la escuela. Una de las partes más importantes de un IEP es la instrucción especializada. El IEP está cubierto por una ley federal llamada Ley de Educación para Individuos con Discapacidades o IDEA, por sus siglas en inglés. Esta ley aplica a todas las escuelas públicas de los Estados Unidos, incluyendo a las escuelas charter. Si su hijo califica para un IEP, usted colaborará con la escuela para desarrollar metas anuales y dar seguimiento al progreso de su hijo a lo largo del año. Por lo tanto, el propósito de un IEP es básicamente ser un mapa que muestra cómo la escuela ayudará a su hijo a ponerse al día con sus compañeros. Y tal vez le sorprenda saber que tener un IEP es muy común. Casi uno de cada seis estudiantes de las escuelas públicas tienen un IEP, es decir, que millones y millones de niños tienen programas de educación individualizados. Cada uno de esos IEP está hecho a la medida de las necesidades individuales de cada estudiante. Así que si su hijo tiene dislexia, el IEP podría incluir una hora de enseñanza especial de lectura varias veces por semana. O supongamos que su hijo tiene TDAH y autismo. Usted y la escuela podrían decidir que su hijo esté en un salón con menos alumnos para recibir enseñanza más individualizada. Estos son los tipos de detalles que se incluyen en un IEP. También es importante saber que la mayoría de los niños que tienen un IEP pasan la mayor parte de su día en aulas de educación general. Por ley, los niños con IEP deben estar en la misma aula que el resto de sus compañeros tanto como sea posible. Hay otra cosa muy importante que todos los padres deberían saber. Tener un IEP no es señal de falta de inteligencia. He enseñado a muchos, muchos niños, y todos mis estudiantes tenían fortalezas y necesidades únicas. Pero a veces las fortalezas de las personas pueden estar ocultas si tienen una diferencia de aprendizaje. Por ejemplo, durante mi primer año como maestra tuve un estudiante que se llamaba Abelardo, a quien realmente le costaba leer y escribir. Lo más que yo le había visto escribir era "sí", "no" y su nombre. Pero un día descubrimos que Abelardo vendía dulces y útiles escolares que traía en su mochila y le iba muy bien en sus ventas. Hacía unas tablas para llevar un registro de su inventario y veía lo que era más popular. Incluso lo tenía codificado por color. Y eso me hizo ver que Abelardo tenía habilidades increíbles de razonamiento matemático y para los negocios, pero necesitaba apoyos formales que le ayudaran con la lectura y la escritura. Así que recuerde, a los niños les puede ir muy bien en ciertas áreas e incluso así, necesitar un IEP que los ayude a progresar en la escuela. [04:53] ¿Qué es un IEP?¿Qué es un IEP? Veamos un poco más los detalles y hablemos de lo que incluye un IEP. Hay muchas partes importantes, pero quiero ofrecerles una descripción general de cuatro cosas fundamentales en un IEP. Lo primero que van a encontrar es una sección que describe el nivel actual de desempeño académico de su hijo. Esto es el término técnico para describir cómo es el desempeño o el funcionamiento de su hijo en la escuela. Es posible que la escuela utilice las siglas PLOP ó PLP o PLAAFP, para referirse al nivel actual de logros académicos y desempeño funcional. Esta parte del IEP destaca las fortalezas y los desafíos del estudiante y cómo se comparan sus calificaciones con las de sus compañeros. También en esta sección puede que se mencionen algunos comportamientos o intereses de su hijo. Por ejemplo, qué materias le gustan y cómo se lleva con otros niños. Después sigue la sección de las metas anuales. Aquí se describe el progreso que el equipo del IEP espera del estudiante. Se enumera cada meta y cada una se divide en metas a corto plazo que se deben ir cumpliendo a lo largo del proceso. El equipo del IEP trabajará con su hijo para lograr estas metas. Más adelante en esta temporada, tendremos un episodio completo para ayudarles a colaborar con la escuela en la creación de estas metas. La tercera parte importante de un IEP es la sección de servicios. En esta parte se detalla cómo el IEP ayudará a su hijo a alcanzar las metas anuales. Esta sección enumera los servicios que recibirá su hijo y por cuánto tiempo. Como por ejemplo: 30 minutos de terapia del habla dos veces por semana. Hay muchos servicios diferentes que se pueden incluir en un IEP, desde servicios de apoyo emocional y terapia física, hasta capacitación en habilidades sociales o manejo del tiempo. Recuerde que la primera letra en IEP significa "individualizado". Así que el IEP puede incluir cualquier servicio especial que su hijo necesita para progresar en la escuela. Y por último, pero no menos importante, esta la sección que describe las adaptaciones o cambios en la forma en que su hijo hace las cosas en la escuela. Esta sección del IEP se conoce muchas veces como apoyos y servicios complementarios. Puede incluir cosas como más tiempo para realizar los exámenes y sentarse al frente del aula para facilitar que su hijo preste atención. También podría incluir tecnología de asistencia, como software de texto a voz o audiolibros. Otra cosa importante que deben saber es que un IEP es un documento legal. En un próximo episodio de esta temporada hablaremos de sus derechos durante el proceso de educación especial. [07:57] ¿Necesita mi hijo un IEP? Muy bien, aquí vamos. Esta es una de las preguntas principales: ¿Necesita mi hijo un IEP? A veces la respuesta a esta pregunta es muy clara: "Mi hijo es ciego y necesita que le enseñen a leer Braille". Pero a veces la pregunta es más difícil de responder. Mi hijo tiene TDAH y necesita mucho apoyo para organizarse y seguir instrucciones. ¿Serán suficientes las adaptaciones en el aula para ayudar a mi hijo a progresar en la escuela? ¿O será que mi hijo necesita de educación especializada? Las escuelas analizan muchos tipos de datos diferentes para determinar qué niños califican para un IEP. En otro episodio de esta temporada, explicaremos el proceso que las escuelas emplean para decidir si un niño necesita educación especial. Pero por ahora voy a compartir un enlace en las notas del programa a un artículo muy útil en Understood que puede ayudarlo a aprender todo sobre las evaluaciones para educación especial. Pero las escuelas no pueden evaluar a su hijo para educación especial a menos que usted lo autorice primero. Así que usted tiene un papel muy importante aquí. Si su hijo está teniendo dificultades en la escuela, puede que se pregunte si son lo suficientemente serias como para necesitar un IEP. Para ayudarlo a decidir, quisiera que se haga unas preguntas. ¿Por qué un IEP ahora? ¿Qué lo hizo pensar en esto? ¿Fue algo que dijo un maestro o que su hijo mencionó? ¿Sus preocupaciones son recientes o las ha tenido durante un tiempo? Pensar en lo que generó sus inquietudes puede ayudarlo a hablar de ellas con la escuela o con el proveedor de atención médica de su hijo. ¿Cómo las dificultades de su hijo afectan su desempeño en la escuela? ¿Su hijo está teniendo problemas con una asignatura en particular, como lectura o matemáticas? ¿Tiene dificultad para socializar o concentrarse en la clase? Intente escribir algunos ejemplos aunque no sepa cuál es la causa. ¿Qué está observando en la casa? ¿Se tarda horas en hacer la tarea y casi siempre termina llorando? ¿Cuán frecuentemente se preocupa su hijo por la escuela? ¿Qué tan intensas son sus preocupaciones? ¿Su hijo se quiere quedar en la casa porque la escuela le resulta muy difícil? Este es el tipo de preguntas que lo pueden ayudar a pensar en qué tantas dificultades está teniendo su hijo y si usted está listo para hablar con la escuela sobre cómo brindarle más apoyo. [10:42] ¿Debería esperar para obtener un IEP para mi hijo? Bien, entonces usted ha notado que su hijo está teniendo dificultades y piensa que tal vez necesita más apoyo en la escuela. Hay una pregunta muy común que los padres se hacen al llegar a este punto. ¿Es ahora el momento adecuado? O ¿mejor debería esperar para que mi hijo obtenga un IEP? He trabajado con muchos padres que querían esperar, porque tenían la esperanza de que su hijo superaría sus desafíos. Pero he descubierto que es mejor atender cuanto antes las necesidades de los niños. Ser proactivo puede tener un impacto positivo en los niños de muchas formas diferentes: académica, social y emocionalmente. Así que si usted tiene dudas sobre si su hijo necesita un IEP ahora o si podría esperar, quiero que haga tres cosas importantes. Primero, pregunte a la escuela qué tipo de intervenciones han probado con su hijo y por cuánto tiempo. Generalmente se llevan a cabo durante varias semanas, y durante este tiempo, la escuela realiza un seguimiento del progreso que está teniendo su hijo. Si usted considera que las habilidades de su hijo están mejorando con la intervención, usted podría decidir que es mejor esperar para solicitar una evaluación de educación especial. Pero usted no tiene que esperar. Puede solicitar una evaluación en cualquier momento. Lo segundo que quiero que haga es encontrar un aliado en la escuela, ya sea un maestro, un asistente u otro miembro del personal.A veces las escuelas cuentan con personas que orientan y ayudan a las familias. Usted puede pedir en la oficina que lo pongan en contacto con uno. Tener una relación con alguien en la escuela en quien usted confíe es importante. Lo ayudará a entender mejor el proceso, hacer preguntas y obtener ayuda para su hijo. La tercera cosa que quiero que considere es el momento del año. Recuerde, usted tiene el derecho a solicitar una evaluación en cualquier momento, pero en la práctica es mejor no hacerlo durante las primeras semanas del año escolar. A menos que tenga inquietudes del año anterior. Igualmente, es mejor evitar solicitar un IEP al final del año, cuando las clases están a punto de terminar. Estas son algunas cosas que lo ayudarán a decidir si es el momento adecuado para hablar sobre un IEP o si es mejor esperar. Solamente como comentario general: sé que muchas familias se niegan a expresar sus preocupaciones por temor a ser vistas como molestias. Y es posible que algunas familias hispanas piensen que no les corresponde decirle a la escuela cómo educar o apoyar a sus hijos. Pero quiero ser muy clara en esto. Las escuelas en los Estados Unidos quieren que las familias informen a los maestros si les preocupa el progreso de sus hijos, y los maestros quieren colaborar con las familias. Así que los animo a hablar con el maestro de su hijo y compartir sus inquietudes. Ya sea que esté solicitando un IEP o no. [13:54] ¿Y si mi hijo está aprendiendo inglés?La última parte de este episodio trata sobre un tema muy cercano a mi corazón, ¿y si mi hijo está aprendiendo inglés? Antes de responder esta pregunta sobre el IEP, quiero mencionar que las escuelas utilizan diferentes términos para describir a los estudiantes que hablan otro idioma en casa. Muchos educadores usan el término "estudiantes del idioma inglés". Yo prefiero el término "multilingüe", y mejor aún, "dotado lingüísticamente". Quiero señalar aquí que todos los niños aprenden los idiomas a ritmos diferentes, y está bien. Y que puede ser difícil dominar el inglés al mismo tiempo que se aprende a leer, escribir y matemáticas en ese nuevo idioma. Esto también puede dificultar saber si los problemas que está teniendo un niño se deben a una barrera del idioma o a otra cosa, como una diferencia de aprendizaje como la dislexia. Hablaremos más sobre esto en un próximo episodio de esta temporada. Por ahora, voy a incluir en las notas del programa un enlace a un artículo de Understood.org que le gustará leer si su estudiante multilingüe está teniendo dificultades en la escuela. Incluye muchas buenas preguntas para ayudarle a pensar si su hijo podría necesitar un IEP. También quiero destacar algo importante: aprender más de un idioma no puede causar una diferencia o discapacidad del aprendizaje. Todos los niños, incluso los que piensan y aprenden de manera diferente, pueden ser multilingües. Las familias me preguntan frecuentemente si deberían de dejar de hablar su idioma nativo con sus hijos porque les preocupa que pudiera ser perjudicial. Esto es falso. De hecho, los expertos en educación recomiendan que las familias sigan enseñando a los niños en los idiomas que utilizan en la casa. Hablar varios idiomas es beneficioso para el aprendizaje y el desarrollo del cerebro del niño. [16:04] Puntos clavesBueno, cubrimos mucha información en este episodio, por lo que me gustaría concluir con algunos puntos claves para ayudarlo a pensar si su hijo necesita un IEP. Piensa en cuánto o con qué frecuencia está teniendo dificultades su hijo. Ser proactivo puede ayudar a su hijo a largo plazo, no solo académicamente, sino también social y emocionalmente. Los niños se pueden desempeñar muy bien en algunas áreas e incluso así necesitar un IEP para progresar en la escuela. Bueno, eso es todo por este episodio de "Understood Explica". Conéctese al próximo episodio para conocer la diferencia entre el IEP y otro tipo de apoyo común en la escuela, llamado el plan 504. Usted escuchó "Understood Explica el IEP". Esta temporada fue desarrollada en colaboración con UnidosUS, la organización hispana de defensa y derechos civiles más grande del país. ¡Gracias Unidos! Si desea más información sobre los temas que cubrimos hoy, consulte las notas del programa de este episodio. Ahí incluimos más recursos, así como enlaces a todo lo que se mencionó en este episodio. Understood es una organización sin fines de lucro dedicada a ayudar a las personas que piensan y aprenden de manera diferente, a descubrir su potencial y progresar. Obtenga más información en understood.org/mission.Créditos:Understood Explica el IEP fue producido por Julie Rawe y Cody Nelson, con el apoyo en la edición de Daniella Tello-Garzón Daniella y Elena Andrés estuvieron a cargo de la producción en español.El video fue producido por Calvin Knie y Christoph Manuel, con el apoyo de Denver Milord.La música y mezcla musical estuvieron a cargo de Justin D. Wright.Nuestra directora de producción fue Ilana Millner. Margie DeSantis proporcionó apoyo editorial. Whitney Reynolds estuvo a cargo de la producción en línea. Laura Key es la directora editorial de la red de Podcast de Understood, el director creativo es Scott Cocchiere y el productor ejecutivo es Seth Melnick.Agradecemos especialmente la ayuda del equipo de expertos, cuyos consejos dieron forma a esta temporada de podcast: Shivohn García, Claudia Rinaldi y Julian Saavedra.

What is autism?

Autism is a neurodevelopmental disorder that affects how people communicate and interact with others and the world around them. It’s lifelong — you don’t grow out of it.Autism often co-occurs with other conditions, like ADHD and learning disabilities. They share common challenges with social skills and communication, including:Trouble reading nonverbal cues or picking up “unwritten” social rulesDifficulty participating in conversation Not always being able to modulate (control how loud you speak, or in what tone)Taking language literally and not always understanding puns, riddles, or figures of speech Another common sign is what’s known as stereotyped behavior. This may look like having a “special interest” around a certain topic or object. Or it can refer to repetitive behaviors and movements like: Arm flapping or rocking (sometimes called stimming)Repeating certain sounds or phrases (sometimes called echolalia)There’s a lot of variation in how autism presents from person to person. Some people communicate by speaking. Others use nonverbal communication. There’s also a wide range in intellectual and self-care abilities. An autism diagnosis reflects this by using Support Levels of 1, 2, or 3. These levels show how much support a person needs, with 3 as the highest level. People talk about autism in different ways. Doctors and schools often use the term autism spectrum disorder (or ASD) and person-first language (“a person with autism”). Some people with the diagnosis prefer identity-first language and may call themselves autistic.Rather than calling autism a disorder, some in the autism community embrace neurodiversity. This concept says conditions like autism are neurological variations that are simply part of human difference.

Understood Explica el IEP

Understood Explica el IEPEl IEP: Las 13 categorías de discapacidad

Es necesario que su hijo tenga discapacidad que corresponda a alguna de las categorías de discapacidad para poder calificar para un IEP. En este episodio, explicaremos de qué se trata. Existen 13 categorías de discapacidad enumeradas en una ley federal llamada Ley de Educación para Individuos con Discapacidades, comúnmente conocida como IDEA por sus siglas en inglés.Para obtener un Programa de Educación Individualizado o IEP, su hijo tiene que cumplir con el criterio de tener una discapacidad que se ajuste a alguna de esas 13 categorías.Los nombres de esas categorías pueden ser difíciles de entender, como “discapacidades específicas del aprendizaje” u “otros impedimentos de salud”.En este episodio de Understood Explica, su presentadora Juliana Urtubey hablará de lo que significan esas categorías y cómo se relacionan con el IEP. También explicará qué hacer si su hijo no califica en ninguna categoría de discapacidad o si califica en más de una.Marcas de tiempo:[00:48] ¿Por qué el IEP tiene categorías de discapacidad?[3:25] ¿Cuáles son las 13 categorías de discapacidad en IDEA?[9:46] ¿Las categorías de discapacidad son las mismas en todos los estados?[12:51] ¿El IEP de mi hijo puede incluir más de una discapacidad?[14:19] ¿Qué pasa si mi hijo no califica para ninguna categoría de discapacidad?[16:00] Puntos clavesRecursos relacionadosLas 13 categorías de discapacidad en IDEA (articulo con infográfico)Centros de capacitación para padres: Un recurso gratuito en su estadoDescargar: Modelos de cartas para solicitar evaluaciones y reportesOpciones para resolver una disputa del IEPTranscripción del episodioJuliana: Para obtener un IEP, los niños tienen que cumplir con el criterio de tener al menos una categoría de discapacidad. Pero, ¿y si la capacidad de su hijo corresponde a más de una categoría? ¿Y si no corresponde a ninguna? Desde la red podcast de Understood, esto es "Understood Explica el IEP". En este episodio, revisaremos las categorías de discapacidad que utilizan las escuelas al decidir si un niño califica para recibir educación especial. Mi nombre es Juliana Urtubey, y soy la Maestra Nacional del año 2021. También soy experta en educación especial para estudiantes multilingües y soy la presentadora de esta temporada de "Understood Explica", que está disponible en español y en inglés. Bueno, comencemos.[00:48] ¿Por qué el IEP tiene categorías de discapacidad?¿Por qué el IEP tiene categorías de discapacidad?. Antes de revisar cada una de las categorías, quiero explicar por qué las escuelas las utilizan. La palabra clave es "elegibilidad". Su hijo no puede obtener un IEP, es decir, un Programa de Educación Individualizado, sino cumple con el criterio de al menos una categoría de discapacidad. Este requisito proviene de la ley de Educación para Individuos con Discapacidades o IDEA, por sus siglas en inglés. Esta ley tiene 13 categorías de discapacidad. Los padres escucharán hablar de esas categorías cuando asistan a la reunión de determinación de elegibilidad de su hijo. El equipo revisará las categorías y dirá si su hijo califica para alguna de ellas. Es posible que escuche el término "clasificación de discapacidad". Para muchas familias, ese es un momento muy emotivo de la reunión. Puede ser difícil escuchar que su hijo tiene una discapacidad, pero siempre pueden pedir hacer una pausa para calmarse y ordenar sus ideas. En un minuto revisaremos cada categoría, pero antes de eso hay algunas cosas generales que quiero que sepan sobre ellas. Primero, IDEA tiene trece categorías de discapacidad, pero eso no significa que solo cubra trece discapacidades. Estas categorías son tan amplias que incluso la condición más inusual podría encajar en alguna parte. Segundo, a veces las dificultades que tienen los niños no son causadas por una discapacidad. Por ejemplo, faltar mucho a la escuela o tener dificultad para aprender inglés como idioma adicional. En esos casos existen otras maneras de ayudar a esos estudiantes, pero para obtener un IEP los niños deben tener una discapacidad. Lo siguiente que quiero mencionar, es que algunas categorías de discapacidad puede que reciban más financiación que otras categorías, pero la categoría de discapacidad de su hijo no puede usarse para limitar los servicios de su hijo. Las categorías de discapacidad son puertas a la educación especial y su hijo solo necesita pasar por una de estas puertas para calificar, así tendrá acceso a cualquier tipo de instrucción especialmente diseñada o servicios que necesite. [3:25] ¿Cuáles son las 13 categorías de discapacidad en IDEA? Entonces, ¿cuáles son las 13 categorías de discapacidad en IDEA? Voy a empezar con las cuatro categorías más comunes, y para ayudarlos a comprender lo comunes que son, quiero que se imaginen un gráfico circular. Esto representa a los millones de niños que tienen un IEP. La porción más grande de este gráfico son los niños que tienen discapacidades específicas del aprendizaje o SLD, por sus siglas en inglés. Aproximadamente, un tercio de los niños con IEP, califican para educación especial porque tienen una discapacidad del aprendizaje. Algunos ejemplos comunes incluyen la dislexia, que algunas escuelas llaman un trastorno de la lectura o una capacidad específica del aprendizaje de la lectura. La discalculia es una discapacidad matemática o un trastorno matemático. También existe la disgrafia y el trastorno de la expresión escrita, donde los niños pueden tener mucha dificultad para expresar sus ideas en un papel. Bien, entonces, los niños con discapacidades del aprendizaje representan aproximadamente un tercio del gráfico circular de la educación especial. La segunda porción más grande es para los impedimentos del habla o del lenguaje. Casi una quinta parte de los niños con IEP están en esta categoría. Este grupo incluye a muchos niños que necesitan terapia del habla, también incluye a los trastornos del lenguaje que pueden dificultar de aprender nuevas palabras o reglas gramaticales o comprender lo que dice la gente. Los trastornos del lenguaje también pueden entrar en la categoría de discapacidades del aprendizaje. Por lo tanto, si su hijo tiene un trastorno del lenguaje, puede que sea un poco complicado elegir la categoría. Bueno, entonces ya está lleno la mitad del circulo de educación especial que estamos dividiendo, y solamente con los niños que pertenecen a dos de las trece categorías, discapacidades específicas del aprendizaje e impedimentos del habla o del lenguaje. Ahora, la tercera porción más grande se llama Otros Impedimentos de Salud, OHI por sus siglas en inglés. Incluye alrededor de 1 de cada 6 niños con IEP. Esta es una categoría muy importante para las familias, porque incluye a muchos niños con TDAH, la ley IDEA enumera una serie de ejemplos que encajan en la categoría de "otros impedimentos de salud", incluyendo TDA y TDAH. También incluye asma, diabetes, epilepsia, intoxicación por plomo y anemia falciforme. Estos solo son algunos ejemplos que se mencionan en la ley, esta categoría es muy amplia. Bien, continuemos con la cuarta porción más grande del círculo, que es el autismo. El autismo incluye aproximadamente al 12% de los niños que tienen un IEP. Esto significa que alrededor de 1 de cada 8 o 9 niños con IEP califican para educación especial porque tienen autismo. Ahora, quiero hacer una pausa y señalar que estas cuatro categorías de discapacidad — las discapacidades del aprendizaje, los impedimentos del habla o del lenguaje, otros impedimentos de salud y el autismo — representan alrededor del 80% del círculo. Entonces, ¿qué pasa con el resto de las categorías? Bueno, están las discapacidades intelectuales que ocupan una porción bastante pequeña, el 6% del círculo, es decir 1 de cada 16 niños con IEP. Algunos ejemplos que podrían estar en esta categoría son el síndrome de Down y el síndrome de alcoholismo fetal. Luego está el trastorno emocional, que representa una porción un poco más pequeña, el 5% del círculo — es decir 1 de cada 20 niños con IEP — y cubre cosas como la ansiedad y la depresión. Y luego hay otras 7 categorías que representan porciones muy pequeñas del círculo. El impedimento ortopédico. El impedimento visual, que incluye la ceguera. El impedimento auditivo, que incluye la sordera. La sordoceguera, que tiene su propia categoría y la lesión cerebral traumática. También hay discapacidades múltiples, esta categoría no se usa si el estudiante tiene TDAH y dislexia. Es más probable que discapacidades múltiples se utilicen para algo como discapacidad intelectual y la ceguera o cualquier otra combinación que probablemente requiere un enfoque altamente especializado. Y por último, están los retrasos en el desarrollo, que es la única categoría de discapacidad en IDEA que incluye un límite de edad. Hablaré más sobre eso en un minuto. Pero por ahora les quiero recordar que no todas las personas con una discapacidad califican para un IEP. La discapacidad debe afectar su educación lo suficiente como para necesitar una enseñanza especialmente diseñada. Este es un ejemplo. Supongamos que su hijo tiene TDAH. ¿Necesita enseñanza especialmente diseñada para poder organizarse y enfocarse en lo que está haciendo? O solo necesita algunas adaptaciones en el aula, como sentarse cerca del maestro y alejado de ventanas o pasillos que lo distraigan. Si no necesita enseñanza especializada, la escuela dirá que no califica para un IEP. Pero puede obtener un plan 504. Si desea obtener más información acerca de cómo los niños califican para un IEP, escuche el episodio cuatro. Y si quiere aprender más sobre las diferencias entre el IEP y el plan 504, escuche el episodio dos. [9:46] ¿Las categorías de discapacidad son las mismas en todos los estados?¿Las categorías de discapacidad son las mismas en todos los estados? La respuesta corta es no. La clasificación de la discapacidad puede ser un poco diferente dependiendo del estado. Algunas de estas diferencias son bastante pequeñas. Por ejemplo, algunos estados usan la frase "categoría de discapacidad" y otros usan el término "excepcionalidad". Y algunos estados tienen más de 13 categorías, porque hacen cosas como dividir el impedimento del habla o del lenguaje en dos categorías. Otra diferencia es como los estados utilizan la categoría de retrasos en el desarrollo. A los estados no se les permite utilizar esta categoría después de los nueve años, pero en algunos estados la edad límite es menor. Por ejemplo, yo vivía en Nevada, y ahí se podía clasificar a los niños con retraso en el desarrollo hasta los cinco años. Y cuando cumplían seis años, mi equipo tenía que determinar si otra categoría de discapacidad se ajustaba a sus necesidades. En la mayoría de los casos, esos estudiantes cambiaban a discapacidades específicas del aprendizaje. Pero en Arizona, que es donde vivo ahora, los niños pueden seguir recibiendo servicios bajo la categoría de retrasos en el desarrollo hasta que cumplan 10 años de edad. Hay otra gran diferencia que quiero mencionar, y tiene que ver con la forma en que los estados clasifican a los niños con discapacidades específicas del aprendizaje. Algunos estados todavía evalúan a los niños para las discapacidades del aprendizaje, utilizando lo que se conoce como modelo de discrepancia. Esto consiste en comparar el coeficiente intelectual o la capacidad intelectual de un niño con su rendimiento académico. Un ejemplo de discrepancia, sería un estudiante de quinto grado con un coeficiente intelectual promedio, pero que lea en segundo grado. Pero algunos estados no permiten que las escuelas utilicen un modelo de discrepancia. Esto se debe a que puede haber sesgos culturales y otros problemas con las pruebas del coeficiente intelectual, incluidas las pruebas que se realizan a los niños que hablan un idioma distinto del inglés en la casa. Así que estas son algunas de las formas en que los criterios de elegibilidad pueden diferir de un estado a otro. Si desea saber cuales son los requisitos de elegibilidad de su estado, pregúntele a la persona encargada en la escuela de conectar a los padres con el personal escolar o comuníquese con un centro de información y capacitación para padres. Estos centros, conocidos como PTI, por sus siglas en inglés, son recursos gratuitos para las familias. Cada estado tiene al menos uno. Voy a poner un enlace en las notas del programa, para ayudarlo a encontrar el centro más cercano. [12:51] ¿El IEP de mi hijo puede incluir más de una discapacidad?¿El IEP de mi hijo puede incluir más de una discapacidad? Sí. Si su hijo tiene más de una discapacidad es recomendable mencionarlas en el IEP. Esto puede facilitar que el IEP incluya todos los servicios y adaptaciones que su hijo necesita. Es posible que el equipo del IEP necesite clasificar las discapacidades según cual afecta más la educación de su hijo. Pero no se pueden usar etiquetas como "principal" y "secundaria" para limitar los servicios que recibe su hijo. Es principalmente una herramienta de recopilación de datos para que los estados puedan tener una idea más amplia de quién recibe servicios y para qué. Y si usted no está seguro de cuál categoría de discapacidad debería incluirse como principal, piense que es lo más importante que los maestros deben tener en cuenta para apoyar a su hijo. Otra cosa que quiero mencionar, es que la categoría principal de discapacidad de su hijo puede cambiar a medida que crece. Un ejemplo es que los niños pequeños que tienen un impedimento del lenguaje podría cambiar a discapacidad específica del aprendizaje a medida que sus dificultades con la lectura o la ortografía se definan mejor con el tiempo. [14:19] ¿Qué pasa si mi hijo no califica para ninguna categoría de discapacidad?¿Qué pasa si mi hijo no califica para ninguna categoría de discapacidad? El equipo puede decidir esto después de la evaluación inicial de su hijo. O, si su hijo ya tiene un IEP, es necesario realizar una reevaluación, al menos cada tres años. Y parte del motivo es para ver si su hijo ya no necesita enseñanza especializada. Si la escuela dice que su hijo no cumple con los criterios para ninguna de las categorías de discapacidad, hay algunas cosas que puede hacer. Lo primero es que revise el informe de la evaluación. ¿La escuela examinó las áreas problemáticas correctas? Quizás el equipo necesite realizar más pruebas en otras áreas. También puede solicitar una evaluación educativa independiente, conocida como en inglés por sus siglas IEE. Esta evaluación la realiza alguien que no trabaja para la escuela, lo más probable es que la tenga que pagar, pero en algunos casos la escuela debe cubrir el costo. Understood tiene un buen modelo para ayudarlo a redactar este tipo de solicitudes. Voy a incluir un enlace en las notas del programa. Estos modelos de carta están disponibles en español y en inglés. Otra cosa que puede hacer es conocer las opciones de resolución de disputas. Más adelante en esta temporada tendremos un episodio completo sobre esto, pero voy a incluir el enlace a un artículo para ayudarlo a comenzar. [16:00] Puntos clavesHemos cubierto muchos aspectos en este episodio. Por ello, antes de concluir, voy a hacer un resumen de lo que hemos aprendido. IDEA tiene trece categorías de discapacidad, pero eso no significa que solo cubra trece discapacidades. La categoría de discapacidad de su hijo es una puerta a la educación especial, no limita el tipo de servicios que puede recibir su hijo. El IEP de su hijo puede incluir más de una discapacidad y la categoría principal puede cambiar con el tiempo. Bien, esto es todo por este episodio de "Understood Explica". La próxima vez, vamos a hablar sobre términos importantes y derechos legales que todos los padres deben conocer si sus hijos califican para un IEP. Acaba de escuchar un episodio de "Understood Explica el IEP". Esta temporada fue desarrollada en colaboración con UnidosUS, que es la organización de defensa de derechos civiles hispanos más grande de todos los Estados Unidos. ¡Gracias, Unidos! Si desea más información sobre los temas que cubrimos hoy, consulte las notas del programa de este episodio. Ahí encontrará más recursos, así como enlaces a los temas mencionados hoy. Understood es una organización sin fines de lucro dedicada a ayudar a las personas que piensan y aprenden de manera diferente, a descubrir su potencial y progresar. Conozca más en understood.org/mission.CréditosUnderstood Explica el IEP fue producido por Julie Rawe y Cody Nelson, con el apoyo en la edición de Daniella Tello-Garzón. Daniella y Elena Andrés estuvieron a cargo de la producción en español.El video fue producido por Calvin Knie y Christoph Manuel, con el apoyo de Denver Milord.La música y mezcla musical estuvieron a cargo de Justin D. Wright.Nuestra directora de producción fue Ilana Millner. Margie DeSantis proporcionó apoyo editorial. Whitney Reynolds estuvo a cargo de la producción en línea.La directora editorial de la red de Podcast de Understood es Laura Key, el director creativo es Scott Cocchiere y el productor ejecutivo es Seth Melnick.Agradecemos especialmente la ayuda del equipo de expertos, cuyos consejos dieron forma a esta temporada de podcast: Shivohn García, Claudia Rinaldi y Julián Saavedra.

I’ve heard that autism and ADHD are related. Is that true?

See a chart that compares ADHD and autism.

ADHD Aha!

ADHD Aha!ADHD, working memory, and feeling like a “burden” (Pablo’s story)

Pablo’s wife noticed his ADHD-related struggles. And he shares a unique bond with his daughter, who has autism. Pablo Chavez forgetful easily distracted, trouble managing emotions. He’s also playful, fun dad. unique bond daughter, autism. Pablo’s wife Britney noticed trouble working memory, encouraged get evaluated ADHD. Pablo reflects ADHD-related challenges sometimes make feel like “burden” home. also positive attitude brings joy people around him.We learned Pablo’s story wrote us! love hearing listeners. email us ADHDAha@understood.org.Related resourcesWhat working memory?ADHD emotionsThe difference ADHD autismPodcast transcriptPablo: So, biggest "aha" moment wife pushing get diagnosis, know, several years big roller coaster really high highs really low lows, depression, anxiety dealing issues. like, no, that's it. know, something change.Laura: Understood Podcast Network, "ADHD Aha!" — podcast people share moment finally clicked someone know ADHD. name Laura Key. I'm editorial director Understood. someone who's ADHD "aha" moment, I'll host.I'm today Pablo Chavez. Pablo electrician, husband, father two lives California. Pablo got touch us via email. wrote us talk us show share story. compelled wanted invite on. thanks coming on, Pablo, thanks emailing us.Pablo: course. Thank you, Laura, me.Laura: anyone listening interested sharing story, email address ADHDAha@understood.org. read emails come in. don't always time respond right away, I'm thrilled hearing amazing people like you, listening show want share story.Pablo: It's honestly really great podcast. I've heard couple stories twice already.Laura: Thank you. means lot me. about, would love know, get diagnosed ADHD? Pablo: September/October 2021 officially got diagnosed. Laura: led seeking evaluation getting diagnosed ADHD?Pablo: That's kind like two-part series struggled change positions work, lot memorization, computer skills, scheduling, planning I'm strong in. boss would often get onto me. Like could forget? It's schedule? It's plan. Laura: again? Pablo: I'm union electrician, subcategorized low-voltage electrician. deal lot systems access control, data networks, CCTV, fire, alarm, DAS systems, fiber optics. I'm communications. I'm actually Airbnb, headquarters San Francisco. company contracted Airbnb manage access control systems globally. manage 16 sites, Beijing, Singapore, Sydney, Paris, Dublin, Portland, Montreal. Yeah, place. Laura: Wow. lot responsibility. sounds like lot manage.Pablo: Yeah, is. is. got yearly review, that's told me, like, performance isn't par. It's well. need step up. telling pushed start seeking help. That's wife told me, think aboutADHD? know, maybe symptoms coincide ADHD is. Laura: noticing? Pablo: Memory biggest part, honest. even going store, she'd send two three things. I'd forget least one, I'd call multiple times. again? again?One thing mention often usually parties, would often ditch her. purposely, right? go, oh, I'm going say hi guys really quick. I'd get caught jump another group go another group. end night, she'd fairly upset. know, barely hung me, know. And — understand someone would feel way. people would like upset significant didn't hang uncomfortable setting her. 'Cause she's introvert.I'm much extrovert. it's purposefully ignoring her, accidentally getting caught things. Laura: Give example. You're bouncing around, you're party you're talking someone. happens? move something else. Tell that. Pablo: Yeah. get — wife likes call giddy. get really giddy, really childlike playful energy. bounce around, conversate. Get excited. People seem eager talk usually seem interested giddiness. like learn. like hear stories. guess like interaction. It's soothing. It's fun.Laura: imagine one things really drew you. giddiness, playfulness. Pablo: Yeah, that's mentioned. soon started taking medicine, little concerned. thought wouldn't anymore, stories she's heard.Laura: case you, maintain giddiness? Pablo: Oh yeah, much. Laura: I'd like go back conversation wife first suggested, could maybe ADHD? remember said you? Pablo: brought lot symptoms. Like would extreme mood swings. I'd either really happy really mad upset. way express anger shutting down, shut down. don't talk. eye contact. I'm barely even there. Laura: maybe trouble managing emotions. accurate? Pablo: Yes, much so. much so.Laura: That's really common actually, Pablo. People ADHD, know, might tend feel anger frustration disappointment intensely others. That's related trouble executive functioning. Pablo: Yes. Oh, one. Executive function. would get stuck nowhere, knowing lot things do, able start. I'd hyperfocused things, one thing, maybe day complete clearness. Laura: describing earlier conversation, sounded like trouble working memory, absolutely sign ADHD. It's like sticky note brain you're storing short-term information. Pablo: Exactly. heard perfect analogy that, helped, kind help explain wife lot people ADHD is. imagine list tasks. sticky notes little cards. put desk shuffle them. That's memory. That's order go in. know, one — don't remember. kind look through, sort, every time. Laura: Pablo, used server restaurant — karaoke restaurant places. remember keep track people's orders. Like would furiously write down. — tell everybody, actually really great server. hyperaware struggled working memory just, never missed beat, right? always, wrote everything point would stayat table little bit long, never forgot anything. wrote down. Pablo: We're adaptive like that. think that's kind drives us little bit knowing fault. perfectionist. wife calls perfectionist, much so. "go big don't it" type attitude. giddiness always "go big." Don't shy away. it. Laura: last spoke, mentioned felt like burden. Pablo: Yes, much so. think rejection sensitivity, believe it's called. think affects quite bit. remember growing up, afraid lot things. lot things. illegal immigrant child. think pushed back further, kind heightened rejection sensitivity. Always felt like burden. felt quiet. Like would rely people say things me. growing up, pretty much same, except lot confident. learned mask lot symptoms, would portrayed quiet scary.Laura: felt like people perceived quiet scary? Pablo: Oh no, know. told me. Laura: told you. Pablo: Yeah. really fit high school. starting quarterback high school pitcher outfielder baseball. went all-league baseball. didn't good football, though, coming quarterback, right, freshman. told really scary, really scary, know, quiet, scary, serious. soon started practicing got know me, like, dude, funny. You're hilarious. You're cool. can't believe afraid you. Laura: That's big difference described terms giddy fun parents. hiding lot.Pablo: much masking lot symptoms high school. Laura: feeling like burden, Pablo, change got diagnosed? Pablo: No. No. don't think it'll ever change don't really control symptoms. feel like always rely people should. it's just, it's something don't want do. I'm learning accept it. I'm learning that, know, like wife wants help me. She's forgiving. She's tend

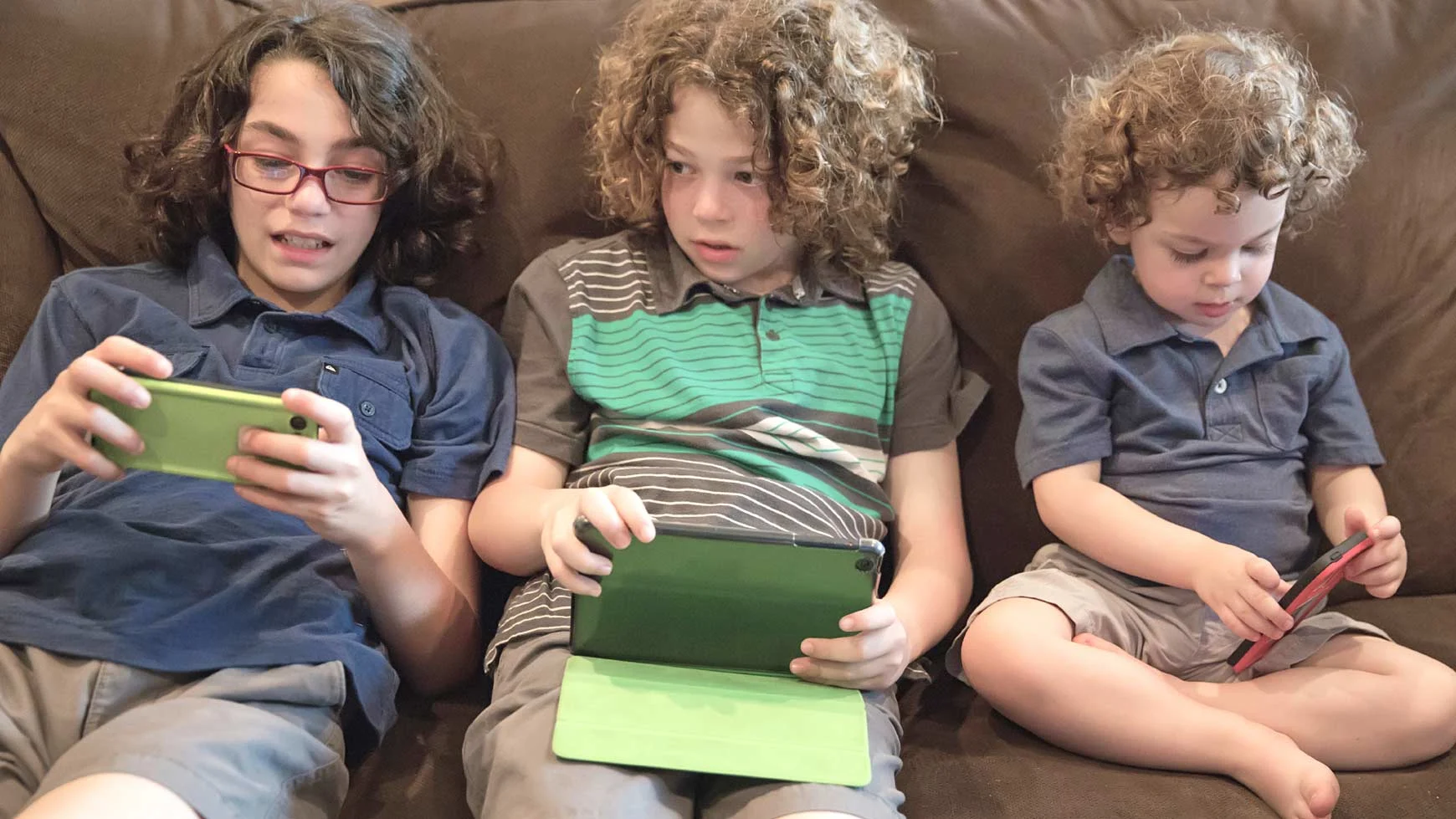

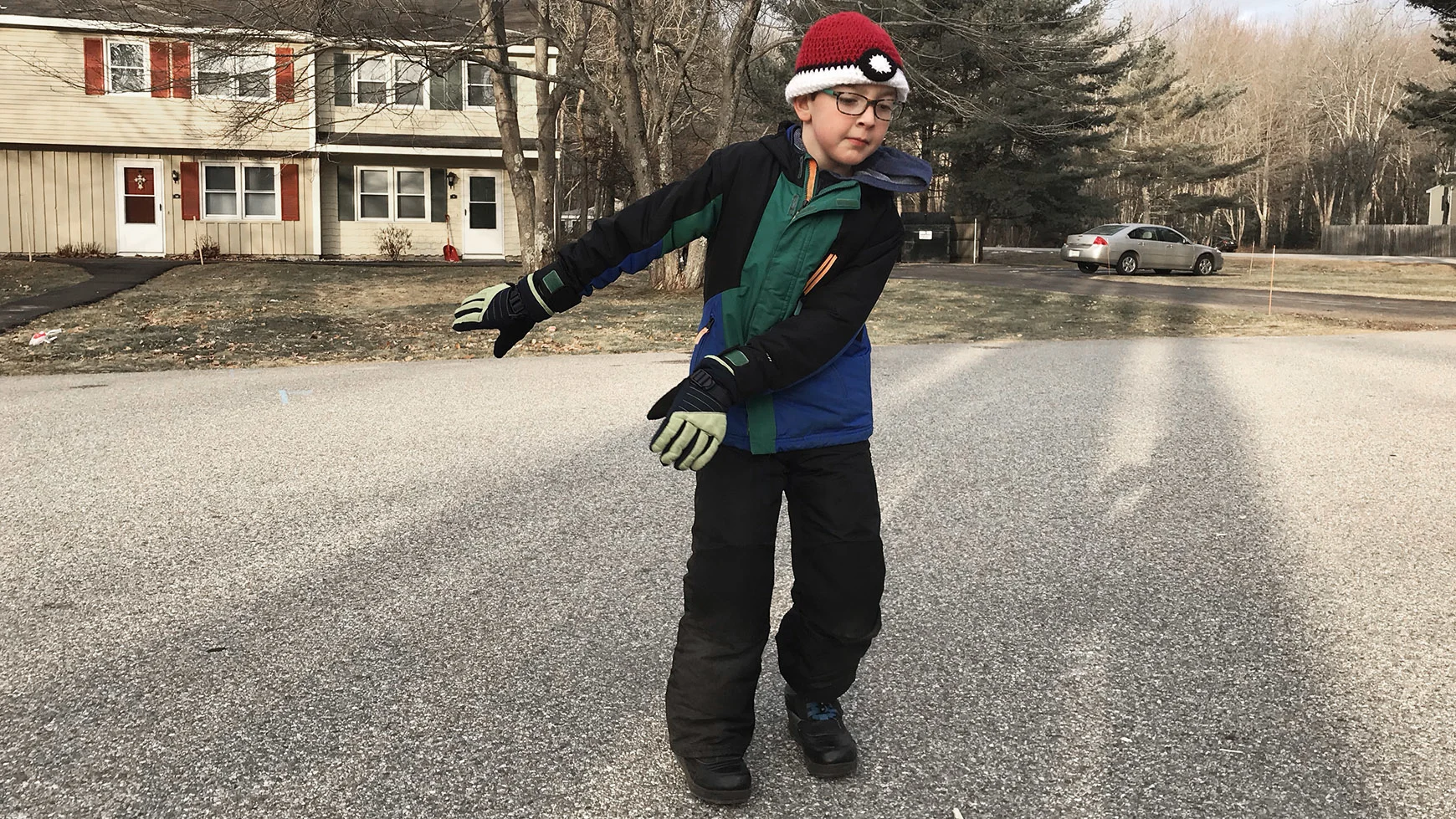

My kids have both autism and learning and thinking differences, and it’s complicated

I have three children. Two of my kids have autism, two have learning and thinking differences, and one has neither. That sounds like the beginning of a brain teaser or a logic puzzle, but it’s not. It’s just my reality.Recently, my younger son was diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder in addition to his ADHD and sensory processing issues. I’m still in shock from his autism diagnosis. And my shock surprises me. That’s because he’s not my first child to receive an autism diagnosis.My older son was diagnosed the other way around — Asperger’s syndrome first, and then we learned later he has executive functioning issues, too. I didn’t struggle with his autism diagnosis. In fact, I was relieved when he was finally diagnosed.Before he was diagnosed, we didn’t have a way to frame his struggles. It was a years-long process of evaluation and of him struggling in school before we had some answers. So I was relieved that he could finally get the supports and services he needed.I was also relieved because none of us had to feel so alone anymore. There was an entire community of parents like us and kids like him.Why was I relieved with our older son’s diagnosis, but now reeling with our younger son’s?Our younger son’s autism diagnosis came two years after he was diagnosed with ADHD. I felt like we’d already found our place with him in the learning and thinking differences community. But then autism was added to the mix. Now I’m not sure which community I relate to.There’s definitely some overlap of symptoms between his autism and learning and thinking differences. For instance, we’re not sure if our younger son’s sensory issues are related to his ADHD, to his autism, or both. His issues with impulsivity and social skills could be a sign of either, too. But some things, like his intense interests in everything about cars and trains, are clearly traits of autism.I don’t know if I’d feel this way if he had, say, ADHD and asthma, like Understood blogger Kerri MacKay. She has both and is an advocate in both communities. But that seems much more clear-cut and easier to sort. Asthma-related symptoms are caused by asthma. ADHD symptoms are caused by ADHD.People send me links to all the cool stories and research studies about autism because they think it might interest me “as a parent.”They also send me links about learning and thinking differences because they think it might interest me “because of what you do for work.” (I’m a former teacher and early intervention specialist, and a parent advocate.)But it’s not that simple. My sons are uniquely themselves. They have challenges that create challenges for me as a parent — challenges that other parents have faced and might be able to help me through.If I’m looking for help, it doesn’t matter if the resources and support I find helpful are autism-specific or ADHD-specific. If it works, it works. If people understand me, they understand me.I don’t want my kids to have to leave pieces of themselves behind. I want them to find support wherever people understand them.I don’t want to have to choose one community over another. And even though my experience is unique, I know there are other families like mine. I don’t want any other parents to feel like they have to choose, either.I think making that happen starts with greater understanding that kids can have both autism and learning and thinking differences. They can have two very separate conditions that need different interventions. But they can’t separate out the different pieces of themselves and put them in neat categories.It would be so much less frustrating if we could sort our kids’ symptoms into an “autism box” and a “learning and thinking differences box.” But we can’t because they blend together.I have three children. Two of my kids have autism, two have learning and thinking differences, and one has neither. Three of them have the ability to make me laugh, make me proud, make me cry, and make me crazy. And they all deserve to belong to any group of kids like them, even if they don’t fit neatly into any one group.

In It

In ItADHD and sleep problems

Many kids with ADHD have trouble with sleep. How can families help kids with ADHD get a good night’s sleep? Many kids ADHD trouble sleep. kids can’t fall asleep stay asleep, many families struggle everybody getting good night’s sleep. In episode, hosts Amanda Morin Gretchen Vierstra talk guests “in it” comes sleep challenges. First, hear Belinda, whose son ADHD, autism, trouble sleeping. Find deals sleep challenges, parent someone struggles sleep herself. Then, hosts get expert advice clinical psychologist, Dr. Roberto Olivardia. Learn connection ADHD sleep. get ideas better sleep toolbox strategies.Related resourcesHow ADHD affects sleep — helpDownload: Bedtime checklists kids Follow Belinda Instagram Twitter see advocacy neurodivergent people. Episode transcriptAmanda: Hi, I'm Amanda Morin. I'm director thought leadership Understood.org, I'm parent kids learn differently.Gretchen: I'm Gretchen Vierstra, former classroom teacher editor Understood, "In It."Amanda: "In It" podcast Understood Podcast Network. show, talk parents, teachers, experts, sometimes even kids. We're offer perspectives, stories, advice people challenges reading, math, focus, types learning differences.Gretchen: Today, we're looking real connection ADHD sleep problems. we'll providing excellent advice help kids can't seem get good night's sleep.Amanda: Later, we'll hear Dr. Roberto Olivardia, clinical psychologist teaches Harvard Medical School, psychotherapy practice Lexington, Massachusetts. specializes working kids learning differences families. He's also Understood expert.Gretchen: First though, we're talking Belinda, mom Florida definitely comes ADHD sleep challenges. Belinda 12-year-old son, she's calling Mr. B protect privacy, kind funny. refer 12-year-old I'm talking publicly makes neurodiverse, call Mr. 12, really good laugh that.Gretchen: Mr. B ADHD autistic, he's gone periods sleep major challenge. Belinda diagnoses, struggles.Amanda: grateful sharing experiences us. We're talking today ADHD affect sleep, something know issue family. get it, I'd really love know little bit son. like do?Belinda: Well, Mr. B, he's son. lets know right away tend get lot extra presents Christmas. he's bright kid. Let's see. plays soccer. loves Roblox, he's playing actually right now. likes Legos. loves read. He's got good sense humor young child. He's little bit precocious. diagnosed ADHD fairly recently, 2018. also diagnosed anxiety time. 2020, went back even though medication, like, "Something's still little off." diagnosed autism. Personally, also recently diagnosed spectrum well, ADHD anxiety. drove get diagnosis felt lot experiences, lot ways reacting, almost like looking mirror. brought back lot past, lot childhood. He's like mini me. It's interesting.Amanda: sounds like lot fun. tell Mr. 12 also ADHD uses phrase "autistic." Mr. 12 ADHD autistic, probably playing something like Roblox room right too.Gretchen: want move sleep, Amanda?Amanda: Yeah, think should. Well, would love move sleep. don't sleep well, would love move sleep. know ADHD make going sleep difficult, I'd really like know looked like son. I'm really wondering it's something also struggled with.Belinda: baby, Spanish, say "ojo duro," means hard eye, difficult fall asleep. 4 a.m. witching hour. he'd put bed, like clockwork 4 a.m. husband would go tend baby. said eyes would like darkness, like kind looking around. infant. mean, 6 months old. Naps were, mean, difficult get nap. would literally drive around fell asleep. also made bit difficult well hearing mom friends, "Oh, mine sleeps night. angel." you're like, "Ugh."Gretchen: Oh, geez.Belinda: yeah, way. Sleep still struggle day me. husband's opposite. lie down, go sleep. problem.Amanda: That's house too. There's something makes want like, "I'm happy also wake up, we're awake right too."Belinda: Yeah.Gretchen: wondered could tell us little bit son baby. know said drove around. things worked? know struggle lots families.Belinda: Yes. things typically used babies, rocking chairs, swaddling. made sure temperature right sleep. slept, wearing. Music soothing. tried also white noise. lot laying chest, lot feel like snuggled, lot rocking, lot late nights.Amanda: goodness. Mr. 12 much way. actually writing book baby, would swaddle him. typing. say today I'm still brushing crumbs top head eating him.Belinda: Yes.Amanda: What's sleep like now?Belinda: Well, started sixth grade. COVID hit state, lockdown. homeschooling. really affected anxiety levels. beforehand sleeping night, post quarantine lockdown now, cannot fall asleep alone. It's real struggle. fall asleep unless someone him. wake middle night, come bedroom, unable sleep. go sleep psychologist. tried medication.Now, say baby, lived beach lived forests, kind cool situation have. beach would tire out. We'd go he'd play waves sand make sand castles. would fall asleep way home. you're talking crumbs, would sand pillow. that's one thing could suggest, younger, definitely tucker out. think nature really great way tire kids get nice fresh air lungs. then, mean, pandemic really made difference. Spotify playlist, weighted blankets, night-light. tried teas. mean, think name it, probably tried it.Amanda: worry going sleep?Belinda: Well, honestly, happens sometimes comes alive night he'll want conversations. thing say conversations important. tells something bothering him, what's heart. He'll start questions, like deep philosophical conversations bedtime. that's OK, I'm like, "It's 11. got go bed. got 6 school." try curb answering quick saying, "Hey, let's talk morning."Gretchen: daughter is... mean, unpacks everything right before.Belinda: old she?Gretchen: 13. everything gets unpacked right then. like said, it's struggle, important conversations want have, 10:00 night. wonder what's Spotify playlist. kinds things helping?Belinda: We've actually looked ADHD sleep. we'll put keywords in, lists come up. There's one that's classical guitar classical piano, need make sure play least eight hours. That's key. stop, could great music, stops hour three hours, he'll up.Amanda: Interesting.Belinda: best tip would be, make sure it's long play loop.Gretchen: question around though.Belinda: Yes.Gretchen: know lots times families worry putting phones bed kids. son ever get distracted anything else he...?Belinda: Well, it's old phone.Gretchen: OK.Belinda: Wi-Fi, calling out. put parentals controls put timer. it's fixed thing access overnight would Spotify go flashlight. might it.Gretchen: No, that's helpful.Amanda: That's good tip.Gretchen: That's good tip. That's good tip.Belinda: Yeah. Now, need someone him. tips. night-lights, music, still needs comfort someone there. weighted blanket. mean, feel like I've tried done pretty much everything. way look is, I'm '80s kid. diagnoses, things, plus South American

The difference between ADHD and autism

Trouble paying attention to people. Being constantly on the move. Invading personal space, not reading social cues well, and having meltdowns. These can all be signs of both ADHD and autism. And the two conditions can occur together.So what’s the difference between ADHD and autism, also known as autism spectrum disorder (ASD)? This table breaks down some of the key differences between them.Learn more about how ADHD is diagnosed. Read one mom’s story of having kids who have both ADHD and autism. And get strategies to help kids manage sensory processing challenges.

In It

In ItBringing sensory differences into kids’ books with Lindsey Rowe Parker

The hosts interview kids’ book author Lindsey Rowe Parker. She talks about her new picture book about sensory differences in kids.From the colors of the classroom to the noises of the playground, school can be overwhelming for kids with sensory processing challenges. One author has turned these experiences into a new picture book. The book aims to help kids who have trouble processing sensory information. In this episode of In It, hosts Gretchen Vierstra and Rachel Bozek talk with Lindsey Rowe Parker, author of Wiggles, Stomps and Squeezes: Calming My Jitters at School. It’s the second in a series of picture books about sensory differences for kids.Lindsey was a child with sensory differences. And now she’s a parent to a daughter with autism and a son who is neurodivergent. Lindsey begins by reading a section of the book. Then she talks about the importance of representation in children’s books. She also shares some of the sensory challenges she faced as a kid, and other real-life stories she included in the book. Related resourcesWiggles, Stomps and Squeezes: Calming My Jitters at SchoolSensory processing challenges fact sheet Surviving the holidays with sensory processing challengesSummer survival guide: Hacks to help your family thrive Episode TranscriptGretchen: From the Understood Podcast Network, this is "In It," a podcast about the ins and outs... Rachel: ...the ups and downs...Gretchen: ...of supporting kids who learn and think differently. I'm Gretchen Vierstra, a former classroom teacher and an editor here at Understood. Rachel: And I'm Rachel Bozek, a writer and editor with a family that's definitely in it. Today, we're calming the jitters with children's book author Lindsey Rowe Parker.Gretchen: Lindsey has a new book coming out, all about a girl with sensory differences. It's called "Wiggles, Stomps and Squeezes: Calming My jitters at School." And it's the second in a series. Rachel: Lindsey herself was a child with sensory differences and is now a mom to a daughter with autism and a son who's neurodivergent. Gretchen: We wanted to talk to her about the importance of representation in children's books for kids like she was, and for her own kids. So, welcome to the podcast, Lindsey. Lindsey: Thank you for having me. Gretchen: We're so excited to talk to you. And we wanted to start by congratulating you on your new book. So exciting. We really, really love it. And so, we were wondering if you could actually read us, maybe the first few pages from it so we can give our listeners a sense of it? Lindsey: Absolutely. "I need to wiggle. I need to spin. I can't explain why. 'Today is a school day, school day!' Mom sings. She takes my hand and we spin, spin, spin around. She makes me giggle with her goofy songs. 'What would you like to wear today?' She asks. I want my favorite shirt. The one with the dinosaur. I point to it. It's in the stinky pile. 'Hmhm. Can we try another shirt with the planets today? \That one is clean and we'll get the dino shirt washed for tomorrow.' I feel my jitters start to bubble inside. Little bubbles. Like the kind in orange soda. She shows me the shirt with the planets. They have sparkles and they match my shoes. I nod. I do like planets, especially Jupiter. That's my favorite. She takes my hand and we spin, spin, spin around. And that's what calms my jitters down." Rachel: Thank you so much for that. And since the listeners can't see the illustrations, I just want to say that the illustrations by Rebecca Burgess really give the reader a feeling of the narrator's sensory experience. Like the spinning and the sounds of the bus, and like, the loudness of the letters on the page that are coming off, you know, from the teacher. I just, I really loved that part of it as well. Lindsey: Thank you. Well, and when I was looking for an illustrator — because we started this process back in, oh goodness, 2019 maybe — and I knew I wanted an illustrator that had the lived experience of sensory experiences. Because it's kind of a, if you don't know what you're looking for, not quite sure how to share that information. So, I reached out to Rebecca on Twitter and I was like, "Hey, I have a crazy idea. Would you read this manuscript? And I would be so honored if you would consider doing a project with me." And they jumped at the opportunity. They themselves are an autistic creator. And since our original partnership, they've gone on to illustrate a bunch of other books. And I'm so excited for that journey for them. I'm so, so lucky to have them on this project with me. Gretchen: That's awesome. So, I'd like to know what inspired you to write a book about a girl with sensory differences. Lindsey: So, I actually didn't start out to write a book about sensory differences. I was just writing little snippets, from, you know, my day with my children. I do have a little girl and a little boy. Both are neurodivergent. One is autistic, and the other, has not been diagnosed yet, but very, very clearly it runs in our family. So, I kind of just was writing these little vignettes or these little snippets of the day. And after going through a lot of occupational therapy with my daughter, I kind of started to see the differences in sensory experiences, and I was able to identify a lot more of the things that I grew up not knowing were sensory differences, I just thought I was weird. And so, kind of through that process, this evolved from just a little snippets of our day to identifying like, "Oh, what I'm actually writing is about sensory challenges." And I like "Oh!" and light bulb went on and I was like, "OK, this makes so much more sense." And we also didn't start out to do this as a series. It was just going to be one book. You know, I'm an unknown author, and it was my first book. And, you know, I thought that was going to be a one and done. And, because of the response from the first book and the need in that space in children's literature for — not only books about sensory differences, but books that celebrate neurodivergence in general — you know, we decided to keep going with it because the response was wonderful. And so, that just kind of I was like, "OK, we're going to keep going, because it's needed." Gretchen: You said when you were working with your own children that — occupational therapy for example — you looked back at your own childhood and sensed, "Huh, maybe some of this was me, too." Would you mind sharing some of the things you realized, maybe you thought you would label as just like, "Quirky," but actually were sensory differences? Lindsey: Oh, yeah. Absolutely. I had so much internal narrative of myself that I've collected over my 40-plus years of — you know, I have ADHD and sensory differences — I was labeled a dreamer. I was labeled as not applying myself. Spacey, obnoxious, like all those things. And it just kind of becomes your internal dialogue after years and years. And going through that process of learning about sensory differences, specifically during my daughter's, you know, therapies, I was like, "Oh, wait a minute." So, I also then got, unfortunately got into a car accident and had to go do some neuropsychological testing. And that's when I actually got diagnosed, was after that. So, while that was a, you know, a hard time of my life, something really beautiful came out of that, which was a diagnosis that I didn't even know that I needed. And it just made so many things make sense. And then I was able to kind of retrain myself in my own narrative and be like, "No, you're not lazy. You're not spacey. You're not, you know — well, maybe I am obnoxious. I'm not sure — and all these things that I thought that I was. I'm like "No, that is not what it is." I think I have ADHD and I have sensory differences and these things I can manage, I can find supports, and I can give myself a little bit of grace, too. And I'm so grateful for that to have happened, even though I'm an adult, it has taught me so much of how I can try and help my kids not create those internal narratives for themselves. Gretchen: Are any of the sensory experiences in the book, ones that either you've experienced in your childhood or that your own children experience now?Lindsey: Oh, absolutely. The food ones, the clothing. I mean, one of the ones that was actually me, in this new book, is when the child is putting their face on the table and the table is really cool. And they're feeling the scratches or the divots in the table. And like, that exactly happened to me as a kid. I would just sit there when I was overwhelmed with whatever was happening in the classroom. I would then just, you know, feel senses around me. So, I put my warm face on a cool table. And it looks like, who knows what it looks like to the teacher that you're doing, or to the other kids. But what you're doing is you're just trying to regulate yourself. And it varies so much from person to person, as far as like, what things are difficult for them. Gretchen: That example you just gave of the head on the cool table and like feeling the little cracks on the desk like, yeah, you're right. To someone from the outside — like, I'm a former classroom teacher — I don't know, I might have looked at the kid and wondered what they were doing. So it's really informative, this book, to teach people that, actually this might be a way that they're calming themselves down amidst all of the commotion that's going around them. Lindsey: Yeah. I mean, it's fun and almost kind of, healing to like, kind of put it on the page and have the outcome be something that maybe didn't actually happen the way that I would have liked it to happen. Some of these responses that we show in the book are not necessarily how those moments actually played out. This is more of how I wish they could have played out. Rachel: Yeah. And I also really liked how understanding, like you said, that the outcome wasn't always how it really went for you or for either of your kids. Because there were moments while I was reading where I'm like, "Oh no, how is this going to go?" And it went OK. So, thanks for that. And so, another thing that struck me in the book is the repeated phrase, "I can't explain why." Like, when the narrator is saying, like, "I need to wiggle, I need to spin. I can't explain why." And it seems like there's something really important that you wanted to get across there. Can you talk a little bit about why you left it there, that you didn't add an explanation or anything specific about a labeling or a diagnosis? Lindsey: That's a great question. I think while I was crafting this, I had a lot of different authors — I was in a group, a critique group — we would get together and read each other's manuscripts. And part of that was saying, like, "How are you going to wrap this up? Like, how is this going to go down?" And, you know, I was like, "I don't know if we need to explain why. I don't know if a child explains themselves like, you just feel it. It is just your reality." And one of my critique partners, he was just like, "That's it. That is your repetition. That is your 'I can't explain why.'" And I was like, "Huh!" And he was so right. And you don't necessarily need to explain why all the time. You just need to be accepted, and supported. And so, even if the child or the adults or whomever it is can't tell you why they're doing the things that they're doing or why they're feeling the things that they're feeling, it doesn't matter. We still need to support and, you know, accept people and meet them where they're at. Gretchen: Lindsey, we mentioned this earlier that, we just appreciate how the story doesn't have, you know, a teacher coming in and saying, "What are you doing? Why are you doing that?" That the teacher is really supportive. And I feel like other authors might have gone the other way, because they might have thought it was more interesting, right? To have like, it's sort of like a children's movie. Some of those movies have these, like really harsh points because they think that that's what kids need. So, why did you choose to not add that? Why did you choose to have such a supportive teacher, supportive friends, etc? Lindsey: This was a definite choice. It took me actually a while to get this book published because, as I was shopping it around to different editors and you know, publishing houses, they were like, "Oh, we like it, but it's too quiet. Your story's too quiet." You know, "There's not enough drama in it. If you could make it a little more..." And I was like, it didn't sit right. And I understand that, you know, their job is to sell things. I get it. But for this specific, you know, I didn't want to do that. I didn't want to make it more than it needed to be. The arc in both of these stories is dramatic enough for the person experiencing it. More things don't need to be added to make that experience valid when other people see it. And so, that's partly why there is no like, huge explosion outside of just internally in that person's experience. And then having these supportive adult figures was so important to me and my illustrator for this particular series, because we want to model the way that it should go for kids. We want kids to see the way it should go for them. And, I was in another interview once with the first book and they said, "So, is this how you respond? And I was like, "Well, sometimes I can, sometimes I mess it up." You know? So, this is not like me doing all the things perfectly in this book. This is me showing what I would love to have happened. And I don't always get it right either. But modeling that type of support from adult figures in a kid's book, I thought was very important, and I was not willing to change that just to get it solved. Gretchen: Yeah, I agree. I mean, when my kids were little and we would watch, you know, the typical kids' movies that had those dramatic moments in them, they hated it because they felt unsafe. They felt like, "Well, what's going to happen? I'm scared." And so, I feel like this book is so great for kids, because they're reading it and they don't have to feel worried for the main character for the most part. And it does feel safe and warm, right? So, I like that about the book a lot. Rachel:Yeah I think it's nice to have a quiet story that is relatable for, especially for kids who maybe don't have a lot of quiet, because they're always getting the like, "What are you doing? Why are you doing that?" And now they're like, "Oh, it's OK here." So, yeah. I love that. So, Lindsey, you haven't just written these two books for your series — and I shouldn't say just two — but you've also recruited other children's book authors and creators to put out stories about sensory needs and challenges. Can you tell us a little bit about how that came about and what's come out of that campaign? Lindsey: Sure. So, I started seeing — as I got deeper down into the children's literature, like industry or environment or community, I guess you could say — I started seeing that there were actually a lot of books coming out specifically for, you know, neurodivergence, sensory differences by autistic authors and illustrators and creators. And I did not necessarily encourage them to write these books. They were already doing it. What I encouraged them to do was come together and not see each other as competition. And more see each other as like collaborators or community. And so, there's probably about 20 or so of us now that are either creators, illustrators, authors and even just advocates and other organizations. And then, during Sensory Differences Month in October, you know, I just really promote all of the different stories that are available and out there that have this, that's not the same story, but it is a similar feeling in the fact that, like, "You're not broken. There's nothing wrong with you, but this is an actual thing that people experience, and sometimes it's hard." And here are a lot of different resources for you to understand yourself, to know that you're not alone. And just to, to kind of like make a community of people who have the same goal. Gretchen: I'm wondering if you've heard from kids or parents and caregivers about your books, like, have you gotten any memorable feedback that's really stayed with you from those families? Lindsey: Yes. I have so many beautiful reviews that it just like each time I read one I tear up a little bit. But I think the one that got me the most, it was in person and I was at a children's hospital reading to the kids. And there were some parents there, and one of them came up to me after, and she was crying. She's like, "Thank you for seeing my child. No one sees my child." She's like, "You see them in this book and they can see themselves." And I was like, "Oooh." And I've heard that, you know, I don't wanna say many different times, but really is a very common thing for them to say. But having a mom in front of my face tell me, with tears in her eyes, that just got me pretty good in the heartstrings.Rachel:Yeah. So, looking ahead, do you have ideas for a next book in your "Wiggles, Stomps and Squeezes" series? Lindsey: Yes I do. Absolutely. So, we have the two — this next one I should actually be getting just like in three days. I can't wait to unbox it — I also have an activity book that goes along with it. But then, aside from those three pieces, I'm hoping to do, I mean, the dentist right now is a big one in our home. So, that's a rough one. So, I'm thinking that might be one of the next ones. Holidays are usually like, sensory nightmares. They can also be really exciting for sensory, because I mean, I'm a seeker for the most part, a sensory seeker. And I love lights and loud noises and all this kind of stuff. But at some point it gets overwhelming. So, I might explore that a little bit. And then travel, you know, going on airplanes or going to new places with your family. That one can also be really fun and exciting, but hard. So, those are kind of the three that I'm toying with manuscripts right now. Gretchen: Those are all so good. I must say, I could really benefit from the dentist. Rachel: Yes, and we did episodes about the overload of the holidays and of traveling. Gretchen: We have, yes. So, we'll have those in the show notes. Rachel: Yeah. But like, yeah, those are big ones. Gretchen: Those are big ones. Lindsey: Yeah. And I try and pull from things that we experience personally, because I feel like most of the time it's so much more authentic to write from something that you understand and know. So, I'm sure there's a million other scenarios that I could write about, but because those are right now pretty, pretty intense for our family, I think that's why I'm gravitating towards those. Gretchen: Yeah. Do you have anything else you want to share before we wrap up? Lindsey: I just... I want kids to know that they are not weird or broken, ever. They're not. And it's — whether that's through books like mine or through other, you know, ways to find that out — I think it seems like there's a shift in the way that we talk about disability. And it seems like it's getting better and more inclusive and more accepting. And I'm very happy to be part of that. And I want to keep pushing that message like, "Hey, you're not broken." Rachel: We wholeheartedly agree. Thank you so much. This was really a great conversation. It was so nice to get to know you. Gretchen: Yes. Thank you for talking with us. Lindsey: Thank you for having me! I was so excited. I love Understood, I think it's such a great organization.Rachel: Lindsey Rowe Parker's new book is called "Wiggles, Stomps and Squeezes: Calming My Jitters at School." Gretchen: You've been listening to "In It" from the Understood Podcast Network.Rachel: This show is for you. So we want to make sure you're getting what you need. Email us at init@understood.org to share your thoughts. We love hearing from you.Gretchen: If you want to learn more about the topics we've covered today, check out our show notes. We include more resources as well as links to anything we mentioned in the episode. Rachel: Understood.org is a resource dedicated to helping people who learn and think differently discover their potential and thrive. Learn more at understood.org/mission. Gretchen: "In It" is produced by Julie Subrin. Ilana Millner is our production director. Justin D. Wright mixes the show. Mike Ericco wrote our theme music. Rachel: For the Understood Podcast Network, Laura Key is our editorial director, Scott Cocchiere is our creative director, and Seth Melnick is our executive producer. Thanks for listening.Gretchen: And thanks for always being "in it" with us.

Hannah Gadsby’s “Douglas” and a later-in-life autism diagnosis

We know that 2020 has been a stressful year for employers, employees, and job seekers. So here’s a snapshot of something we’ve found useful or motivating. Whether it’s a tip for how to stay on top of work, or something to take your mind off the news, we hope it’ll be a positive and helpful way to round off your week.Australian comedian Hannah Gadsby is probably best known for her comedy special, Nanette, which won her an Emmy in 2019.She’s followed it up with another comedy special, Douglas, which toured the U.S. last year and is now available on Netflix. In both shows, Gadsby talks about her later-in-life autism diagnosis, and how getting diagnosed helped her come to a better understanding of herself. Many people with autism are diagnosed later in life, or not at all — especially girls and women. And many people with disabilities or learning and thinking differences choose not to self-disclose at work. Gadsby’s description of her experience can help people who don’t have autism better understand their colleagues, employers, and employees who do.Here’s an interview in which Gadsby talks about her autism diagnosis and her approach to discussing it in her show.Douglas is available for streaming on Netflix.

In It

In ItThis is how we make it through