57 results for: "gifted"

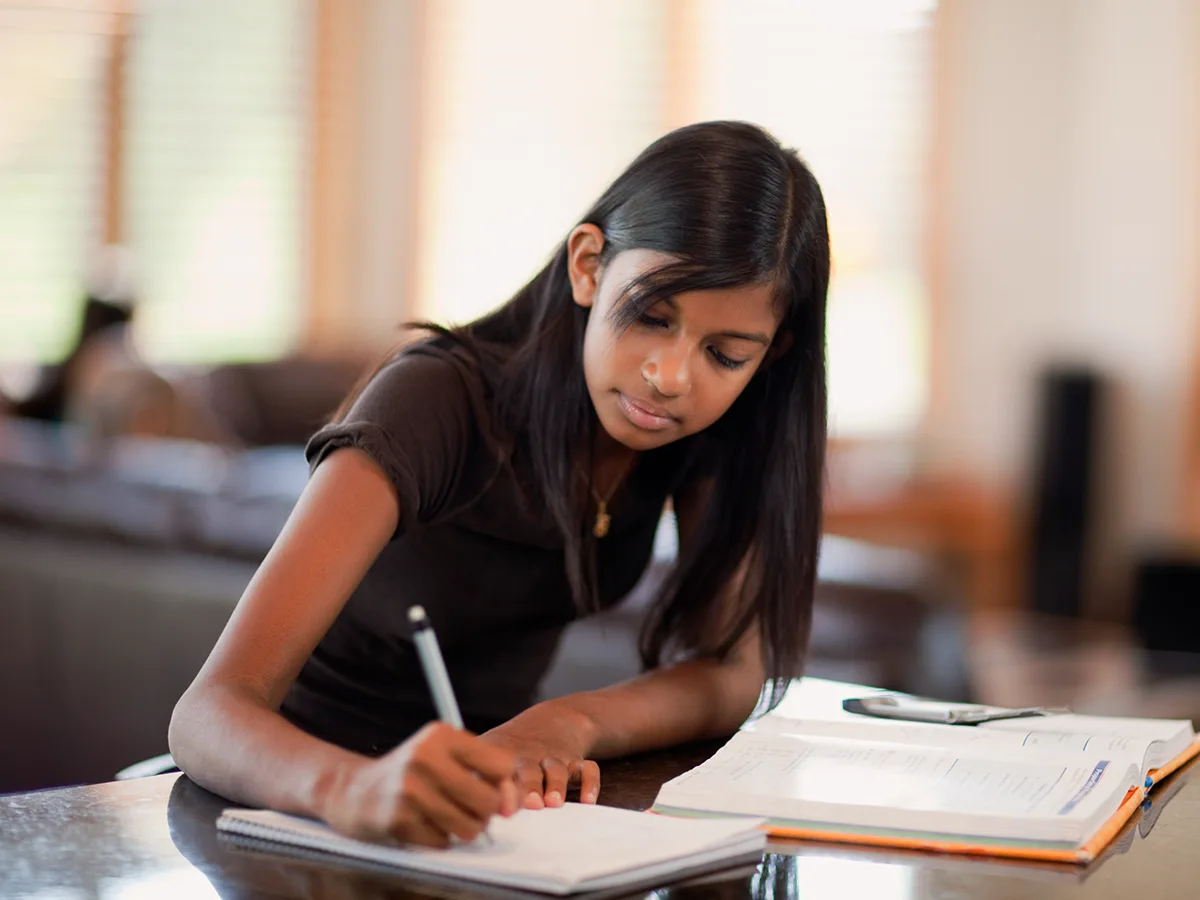

The challenges of twice-exceptional kids

“Your child is gifted and needs special education?” Many parents are all too familiar with this kind of comment. You may hear it from friends. From family. Even from some teachers and doctors.Yet there are lots of people who have exceptional ability in some academic areas and significant learning difficulties in other areas. Educators use a special name to describe students who qualify for gifted programs as well as special education services. These children are referred to as twice-exceptional, or 2e, learners.“Some organizations estimate that there are hundreds of thousands of twice-exceptional learners in U.S. schools.” Consider Tessa: She’s a bright, insightful, and enthusiastic fourth grader who is reading at a 12th-grade level. At the same time, she can’t pass her spelling tests, and writing is a huge struggle.Consider Jamie: At 16, he knows everything about the Civil War, writes beautifully, and can talk endlessly about politics. Yet he needs a calculator to help him with even the most basic math. And he couldn’t tie his shoes until he was in seventh grade.Consider Steven Spielberg: He’s one of the most successful filmmakers of all time, but reading has been a lifelong struggle for him because he has dyslexia.Twice-exceptional and easily overlookedSome organizations estimate that there are hundreds of thousands of twice-exceptional learners in U.S. schools. But there are no hard numbers because so many of these students are never formally identified as being gifted, having a disability, or both.Twice-exceptional children tend to fall into one of three categories. These categories help explain why students often go through school without the services and stimulation they need:Students whose giftedness masks their learning and thinking differences. These kids score high on tests for giftedness but may not do well in gifted programs. These students use their exceptional abilities to try to compensate for their weaknesses. But as they get older, they may be labeled as “underachievers” or “lazy” as they fall behind their gifted peers.Students whose learning and thinking differences mask their giftedness. Learning and thinking differences can affect performance on IQ tests and other assessments for giftedness. For example, since many of these tests require language skills, kids with language-based challenges may not perform well. These kids may be placed in special education classes, where they become bored and possibly act out because they aren’t being challenged enough. Some of these children are identified, wrongly, as having emotional problems.Students whose learning and thinking differences and giftedness mask each other. These kids may appear to have average ability because their strengths and weaknesses “cancel each other out.” Consequently, these students may not qualify for gifted programs or for special education programs.Identifying twice-exceptional studentsFederal law protects students with disabilities. School districts are required to look for children with disabilities and provide special education to those who qualify for it. Gifted education is a different animal.There is no federal requirement for gifted education. Decisions about gifted programming are made at the state and local level. Few states specify what these services should be and which talents should be nurtured. This is often left up to individual school districts. And funding for gifted services can vary greatly from district to district.Identifying twice-exceptional students tends to be a low priority. Often it takes a proactive parent to push for testing for both giftedness and learning and thinking differences. But sometimes teachers are the first to raise the possibility.Here are some early tip-offs that your child could be a twice-exceptional learner:Extraordinary talent in a particular area, such as math, drawing, verbal communication, or music A significant gap between your child’s performance in school and performance on aptitude testsSigns of a processing disorder, such as having trouble following spoken directions or stories that are read aloudThere isn’t a simple, one-test way of identifying twice-exceptional children. Ask your child’s school how it evaluates kids for giftedness and learning and thinking differences. The process usually includes assessing kids’ strengths and weaknesses as well as observing them in class and other settings.It may be helpful for you and the teachers to keep records of what your child excels in and struggles with. Be on the lookout for “disconnects” between how hard your child is studying and what kinds of grades your child gets.Social and emotional challengesGiftedness can add to the social and emotional challenges that often come along with learning and thinking differences. Here are some challenges that twice-exceptional learners may face:Frustration: This is especially common among kids whose talents and learning differences have gone unnoticed or only partially addressed. These students may have high aspirations and resent the often-low expectations that others have for them. They may crave independence and struggle to accept that they need support for their learning and thinking differences.Like many gifted students, twice-exceptional learners may be striving for perfection. Nearly all the students who participated in one study of giftedness and learning disabilities reported that they “could not make their brain, body, or both do what they wanted to do.” No wonder these kids are frustrated!Low self-esteem: Without the right supports, children with learning and thinking differences may lose confidence in their abilities or stop trying because they start to believe that failure is inevitable. This kind of negative thinking can add to the risk of depression.Social isolation: Twice-exceptional kids often feel like they don’t fit into one world or another. They may not have the social skills to be comfortable with the students in their gifted classes. They may also have trouble relating to students in their remedial classes. This can lead twice-exceptional learners to wonder, “Where do I belong?” These children often find it easier to relate to adults than to kids their age.How to help your childWith the right supports and encouragement, twice-exceptional learners can flourish. (Just ask Steven Spielberg!) Here’s what you can do to help your child:Talk to the school. If you suspect your child may be twice exceptional, request a meeting with the school’s special education coordinator. Discuss your concerns, and ask about types of tests.Ask to stay in the gifted program. If your child has been identified as gifted but is not doing well in that program, request an assessment for learning and thinking differences before any decisions are made about removal from the program.Make the most of your child’s IEP. If the school determines that your child is twice exceptional, use the annual goals in the Individualized Education Program (IEP) to address weaknesses and nurture gifts. Be prepared to brainstorm — and to be persistent!Find other twice-exceptional kids. Encourage your child to spend time with children who have similar interests and abilities. This can help kids celebrate their strengths and feel less isolated. You may be able to connect with twice-exceptional families through Understood’s Wunder community app.Empower your child. It’s important for kids to understand their gifts and weaknesses. Reassure your child that kids can get support in the areas where they struggle. But resist the urge to rush in and rescue your child every time something is frustrating. It’s better to help kids learn to cope with their mixed abilities.When caregivers partner with teachers, it can help kids develop their talents and achieve their full potential. Learn more about how to be an effective advocate for your child at school. With love and support from their family, kids can move ahead and make the most of their gifts.

In It

In ItWhen gifted kids need accommodations, too

Meeting the needs of kids with learning and thinking differences can be a lot. Add giftedness into the equation, and parenting takes on a whole additional dimension.Meeting needs kids learning thinking differences lot. Add giftedness equation, parenting takes whole additional dimension.That’s Lexi Walters Wright hears co-host Amanda Morin episode raising twice-exceptional (or “2E”) kids. Amanda swaps shared experiences guests Penny Williams, parenting trainer coach, Debbie Reber, author creator TiLT Parenting — raising 2E sons.They talk finding right school program students gifted struggling. also rethink intelligence really means hope future looks like 2E young adults.Related resourcesGifted children’s challenges learning thinking differences12 questions ask school 2E studentsA unique IEP solution twice-exceptional sonDebbie Reber’s TiLT Parenting PodcastPenny Williams’ Parenting ADHD PodcastEpisode transcriptAmanda Morin: Hi. I'm Amanda Morin, parent kids learning differences — writer Understood.org.Lexi Walters Wright: I'm Lexi Walters Wright, community manager Understood.org.Amanda: "In It." Lexi: "In It" podcast Understood Parents. show, offer support practical advice families whose kids struggling reading, math, focus learning thinking differences. Amanda: today we're talking supporting kids learning differences gifted. Penny Williams: That's something we've heard teachers long time. know, he's told, "I don't understand can't this. You're smart."Lexi: Penny Williams writer best known book, Boy Without Instructions. Amanda: boy she's referring son, Luke, teenager.Penny: Luke 16. No, he's driving yet. ready yet. Amanda: Luke intellectually gifted. also learning thinking differences. parents figure deal gifts home, school world. Lexi: Amanda, we're going get Luke Penny's story minute. first want ask you: There's term people often use kids gifted disability. It's "twice exceptional," "2E" short. I'm guessing listeners hearing term first time thinking. "Well, what's big deal? Isn't like, kid learning disability that's tricky — hey, bonus, it's bad gifted?"Amanda: Wouldn't nice easy, right? twice exceptional 2E, think key exceptionality. We're talking exceptionalities rare ways. kid learning disability, means they're struggling type processing learning difference kind thing. kid who's, like, sort off-the-charts really smart way separates rest kids class also. concern twice exceptionality makes really tough oftentimes one "E" mask other. kid who's really strong one area — gifted — learning disability learning difference gets way makes look average. sometimes you'll see giftedness really good job masking disability.Lexi: topic know lot about, Amanda. So, parent advocate also parent. Amanda: Oh yeah, definitely. two twice-exceptional kids home. don't know math is. Exponentially? It's challenge. Lexi: give us example know 2E kids? Amanda: house? give example house. looks different everybody's house. So, example, yesterday — live Maine. snow day 9-year-old, one twice-exceptional children, said him, "Hey, it's snow day!" says me, "Great, I'll sitting reading interview CEO Mitsubishi 'Motor Trends Magazine.'" Whereas expected be, like, "Cool, I'm going put pajamas hang playing LEGOs." Lexi: son also learning thinking differences. Amanda: Yeah, also ADHD autism, he's sort wrapped that. teenager also twice exceptional, thinks amazing ways. deep conversations. yet can't seem grasp idea left hat room last place saw hat, hat literally room somewhere — didn't walk off. sounds like lot teenagers, literally it's idea still hard keep mind. Caller 1: three 2E kids one stories aware kid struggling son 3 years old. reading, pretty much, words since 2. noticed also really hard time keeping together nursery school. said "he's either gifted bored ADHD" actually turned both. true. Caller 2: third grade started getting calls son saying, "I think I've tried hard enough today, Mom. It's time come home." People always focusing deficits challenges misinterpreting actions. Reading class actually way calm nervous system pay attention. brain's way doodling. Caller 3: hardest thing get people understand 2E kid lazy unmotivated. actually story: ninth grade, finally able get advanced class, math class. teacher upset able get class went principal told son unorganized immature class. principal pulled son's file showed teacher son's math scores. that, told son highest math scores entire K 12 school. deserve class also let know teach son. Lexi: today's episode, we're going draw experience, Amanda, we're also going hear two moms whose paths taken many twists turns try make sense learning strengths challenges children have.Amanda: First we're going go back Penny, mom Luke. Lexi: Luke little, Penny husband didn't know "gifted," "learning disabled," "2E," labels. knew sweet, smart, curious kid. Amanda: started school. Penny: Kindergarten disaster. one worst years we've had. October birthday kid. still 4, could see super, super intelligent. So, know, knowing anything, went ahead started. end second day, parent-teacher conference. morning second day already called me: "You need stay pick up, talk." Like, oh, great. thought, well, he's prepared. know, didn't go preschool. stayed grandma working thought, know, really need give time. Lexi: calls notices kept coming. "He's sitting still, he's wiggling much carpet time. He's flailing scissors, endangering kids." Penny: know onus put us, hadn't prepared work fit classroom. know, one ever said "hey might something else going on." know, "This could learning disability. could developmental disability. know, might want go pediatrician." Lexi: Penny husband figured school problem. next year, switched. new school seemed like much better fit. Penny: amazing teacher first grade differentiated instruction. kind sweet understanding flexible kids' needs. sort notes coming home: Luke can't stay task, Luke behind reading, Luke doesn't control body. know, notes kinder, still issues. that's ultimately led us pediatrician, developmental pediatrician ADHD diagnosis. Lexi: team evaluation recommended Luke try medication ADHD. Penny hated idea. could see needed something Luke. Penny: really, really suffering. sad time. crying time. mean really severely affected fact couldn't meet expectations people didn't understand him. Lexi: So, Amanda. relate story?Amanda: relate story really hits home me. time child feels like they're meeting expectations really hard. can't meet people don't believe true, it's much worse. don't know you, Lexi, I've never met kid wants stand crowd negative way, happen giftedness learning differences. know Penny I, quirky, amazing kids think differently many ways, it's hard makes stand apart want fit in. Lexi: Well, Luke began taking medication ADHD, help some. Penny could see things going Luke, years later

A government reminder to schools: Don’t overlook twice-exceptional kids

Many gifted children also have learning or thinking differences. But if they’re doing well in school, their issues may not be recognized. Schools can be reluctant to evaluate kids like these for special education services.So in 2015, the Department of Education (ED) issued a reminder. The message? Students who are “twice exceptional” are entitled to evaluations, too.Melody Musgrove was director of the Office of Special Education Programs at the Department of Education. She sent the reminder to state special education directors in April.Her memo talked about “children with disabilities with high cognition.” It stated that they’re also covered by the Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act (IDEA). And it asked the state directors to remind schools: They must evaluate all children who may have a disability.There’s another side to this situation, too. Kids who do get IDEA services are often shut out of gifted programs. The National Center for Learning Disabilities (NCLD) reported on this in 2014. And the Civil Rights Data Collection shows that twice-exceptional kids are underrepresented in gifted programs.“Too often, kids with learning and thinking differences are precluded from participating in gifted programs,” says Lindsay Jones. She’s the director of public policy and advocacy at NCLD. Jones adds that schools often believe these kids can’t achieve in these classes, but that’s not true.Jones thinks that Musgrove’s memo and this data can be useful to parents of twice-exceptional kids. “These are great tools to help parents start important conversations with their schools,” she says. Such talks, ideally, can “ensure that all children get what they need to truly thrive.”Any opinions, views, information, and other content contained in blogs on Understood.org are the sole responsibility of the writer of the blog, and do not necessarily reflect the views, values, opinions, or beliefs of, and are not endorsed by, Understood.

ADHD Aha!

ADHD Aha!Twice exceptional: Raising a gifted son with ADHD (Emily’s story)

From a very young age, Emily’s son would have meltdowns and get intensely angry. He was also really bright. From a very young age, Emily Hamblin’s son would have meltdowns and get intensely angry. He was also really bright. He was ahead of the curve academically and scored in the 99th percentile on standardized testing. His teachers would say he was just “smart and quirky.” That didn’t sit right with Emily, though. She knew something else was going on.Then one day, a friend suggested that Emily look into ADHD. Emily was skeptical at first. But when she learned more, it was clear that this was the missing puzzle piece. Her son was twice exceptional: He’s gifted and he has ADHD. This discovery even helped Emily recognize ADHD symptoms in herself.Emily co-hosts a podcast called Enlightening Motherhood, which aims to help moms who are overwhelmed by their kids’ big emotions. Listen in to hear how Emily reframes ADHD symptoms in a positive light.Related resourcesThe challenges of twice-exceptional kids7 myths about twice-exceptional (2e) students Twice-exceptional Black and brown kids (The Opportunity Gap podcast episode)Episode transcriptEmily: I had a friend and I heard her talking to someone about her child's behaviors. And I kind of stopped in my track because it was the first time I heard someone describe my son's behaviors. At the time, I took it as, "Oh, he's just disrespecting me." But finally, that friend said, "You know, that sounds like impulsivity. Have you ever thought that he has ADHD? Because emotional dysregulation is also a part of ADHD." And I was like, "No, no, no. There's no way he has ADHD. He can sit down and read a book without blinking for three hours. If he had ADHD, he couldn't focus that long, right?" And I of course, I fought against it. Then I looked it up and was like, "Oh, my goodness."Laura: From the Understood Podcast Network, this is "ADHD Aha!," a podcast where people share the moment when it finally clicked that they or someone they know has ADHD. My name is Laura Key. I'm the editorial director here at Understood. And as someone who's had my own ADHD "aha" moment, I'll be your host. I'm here today with Emily Hamlin. Emily is a life coach and a mom to a son who's gifted and has ADHD. She's also the host of "Enlightening Motherhood," a podcast dedicated to empowering moms of kids with big emotions. Hi, Emily. I'm so happy to have you on the show today.Emily: I'm so excited to be here. Thank you.Laura: Let's start by telling our listeners and me about your son.Emily: I'm going to use a pen name for him just to keep his identity a little bit confidential. I'll call him Jack. Jack has always been so bright. He was the kid when he was one year old, and we brought him up to the light switches he would study which light turned on. We'd see him turn and predict which one it was and get this look of satisfaction when he got it right. And so he's always been really, really bright. And when he was in preschool —he was 3 years old — I remember he started to have some kind of really intense behaviors. He would have meltdowns and scream and just become so intensely angry. And I felt like it wasn't very normal, like the twos were actually OK. Everyone says terrible twos, but for us, it was 3 and 4 that was when the, those kind of behaviors started popping up. But I kind of felt that it wasn't super typical.And I went to his preschool teacher and I remember saying, "He's doing great academically, but we're seeing these behaviors pop up." And she would say, "Oh, no, he's just copying the other kids, throwing fits at school," or "Oh, he's just a little bit quirky because he's so bright." And in kindergarten, he was reading 100 sight words before kindergarten, and he went to school, and they would say, "OK, well, here's the letter 'A.' It makes the sound 'Ah.'" And so, he would start to act up in kindergarten. And again, the teacher would call me in and she said, "Well, let's just skip him to first grade. I think that will solve all of his behavioral issues." And I was like, "Oh, he's already the little kid in kindergarten. I don't want to have him be this tiny kid in first grade," but that's kind of what was offered.So, we tried a lot of, you know, sticker charts and what I could at the time, never really figuring out the underlying issue. And we got him through that patch. First grade, he had a really good teacher who recognized "OK, he does not need to sit and read line by line with us in this book. Here, Jack, you can bring this book to the corner. You can read at your own pace." And it was like the perfect fit that we've ever had for him for schooling, but he still told me one time, "Mom, we had to partner read on the rug in school, and the book was just so easy that I decided to lay down out on the rug and roll around and make noises instead."Laura: Oh, wow. So, is this about the time that you discovered that Jack was gifted?Emily: Yes. They tested him in school, and he tested 99th percentile gifted. And there wasn't really a gifted program, but his teacher was accommodating him as much as she could. And it was really great because the homework was the worst when he already knew how to do it beforehand. And he would come home with, "OK, write the word 'cat.'" And he was reading Harry Potter at that point in time. It was like pulling teeth to get him to do it, even though it would only take him about five minutes or so, right? But he would throw a fit for about 40 minutes over not wanting to do the homework. And I couldn't quite figure him out. At this point, I really was suspecting that he was neurodivergent and I went to Google.Laura: Dr. Google.Emily: Yeah, Dr. Google. And I thought maybe he has autism. I don't know. And I went to his teacher, and I said, "Do you think Jack has autism?" She said, "No way. He's just smart and quirky." And that was what they always would say, "No, he just has these little, like, behavioral quirks to him and he's smart, and the two combined," and it wasn't really explaining the intense emotions, which is the hardest thing for us as parents to handle. So, it was not until third grade, where I had a friend and we were at a workout group and I heard her talking to someone about her child's behaviors. And I kind of stopped in my track because it was the first time I heard someone describe my son's behaviors, where he made a little mistake on his homework, and then suddenly he ripped it up and then he was raging for like 20 minutes over this little mistake on his homework. And I stopped in my tracks, I was like, "Can we connect?"And I don't remember exactly where it went from there, but I just remember her being this support. And I would say, "No, I just, I need him to listen to me when I say 'stay off my phone' and he walks past my phone and he gets on my phone and it's like he just ignores me and he disrespects me because he gets on it anyways," I had no idea what impulsivity was or what it meant. But looking back, that's totally what was going on. He just couldn't control that impulse. Whereas at the time I took it as, "Oh, he's just disrespecting me." And the teachers would say, "Oh, he's just been bad in class," or "He won't listen to us." Nobody understood any of that underlying things.But finally, that friend said, "You know, that sounds like impulsivity. Have you ever thought that he has ADHD? Because emotional dysregulation is also a part of ADHD." And I was like, "No, no, no. There's no way he has ADHD. He can sit down and read a book without blinking for three hours. If he had ADHD, he couldn't focus that long, right? Or he couldn't sit still that long, right?" Of course, that's what I thought. What everyone says on your show, what we thought and what we know now.Laura: That's what we do here. Yeah, that's right. So, it sounds like that was the start of your ADHD journey. Maybe your ADHD "aha" moment for your son.Emily: Yeah. And I, of course I fought against it. Then I looked it up and was like, "Oh my goodness." Like it was the whole package. It's not just "He can't pay attention and he can't sit still." It had that whole package, and I went to his third-grade teacher who was really close to students and really perceptive of them, which was great, and I said, "Do you think he might have ADHD?" It was like, "Yes, please go get him evaluated."Laura: Wow. What happened then? How did the evaluation process go?Emily: We just found an ADHD clinic and she emailed us all the forms ahead of time. So, we only had one in-person visit, but filling them out, we did the NICHQ, and looking through those questions and filling them out for him, I was like, "Oh my goodness." He was marking pretty much everyone. I don't remember the exact scale, but like very often, I think is what the highest one pretty much everyone was very often. And as I was filling it out for him, I had my own "aha" moment where I went, "Oh my goodness, I'm checking all these boxes, too." And I never even considered that I could have ADHD. But suddenly it explained my own emotional dysregulation and my own tendency to just get lost in time and not realize that time had passed or procrastination, things like that. It was like a double "aha" moment.Laura: Your son is twice exceptional. Could you define that for our listeners? This is the first time we've had the opportunity to talk about twice exceptional or 2e on the show.Emily: So, he's twice exceptional in it that on the one hand, he is academically gifted, but he also has this additional neurodiverse side to him, which for him is ADHD. So, he has both going on at the same time. Getting that diagnosis was kind of difficult because it was almost like the giftedness was masking the ADHD. He was compensating with his ability to do so well in academics, but we didn't notice really what was going on.Laura: It's so tricky already to spot signs of ADHD. There's so many misconceptions about ADHD and how it presents. That's just got to add this extra layer of misconceptions or confusion.Emily: Yeah, and there's kind of a social conception, too, that children that are academically gifted should be quirky. And so, they would just describe all of those quirks as a result of his giftedness that it couldn't be something else.Laura: Because your son is academically gifted. I imagine there are all these expectations around what he's supposed to be able to do, and he's supposed to be extra mature and extra good at everything. Do you find that that's true?Emily: Yeah, and I had that for a long time, too. I would say "You're too smart to be melting down over brushing your teeth. Can't you see that brushing your teeth will take you three minutes and this fit is taking you 15 minutes? Why don't you just brush your teeth? Why can't you be logical? You're smart enough."Laura: Did you ever feel judged as a parent during this journey?Emily: I mean, definitely. I feel like most parents feel judged for their children's behaviors, and I just felt like it took so much more effort and people didn't realize that I was trying. I would get like phone calls home, "Oh, Jack did this again in class," and I would be like, "OK, I'm working on him and I'm trying." And he was doing his best too. For him, it was frustrating. There was one time he was probably five or six and a neighbor girl came over to invite him to go to the park and she knocked on the door and we answered it and she said, "Hey, Jack, want to come play at the park with me?" And her dad was with her. It was a really safe situation, but he didn't know how to handle it. So, he just like froze and he turned around 180 degrees and just let her stare at the back of his head, and he just shut off.Laura: Oh, wow.Emily: And then they're looking at me like, "So what's going on with your son?" And I'm looking at my poor son, just my heart breaking. I don't know if they were judging me, but at the time, I felt judged. I could imagine them thinking, "Why can't you teach your son social skills instead of realizing, "Oh, your son is trying so hard. He just had a hard time."Laura: From that moment to where you are now, what kinds of things helped you cope with feeling, judged, and what kinds of strategies maybe brought you and Jack closer together or things that you would say?Emily: Mindset is huge. Realizing that he wasn't just trying to be bad, or he wasn't choosing to be impulsive and he wasn't intentionally melting down, realizing that he was really doing his best. There was just a lot going on for him. That helped me out a lot. Also starting to see behavior as communication of something bigger. That was a huge deal. Like, that's probably the biggest thing that I tried to share with everyone.My website has a freebie on why is my child melting down and what's at the root of their intense emotions. And it's this five-step cheat sheet that I, I try to just get everyone to take a look at because the more that we understand that "My child is not intentionally being bad, it's not their fault. It's not my fault. They just need help developing these skills." Like, it just changed me from being upset and trying to get him to behave a certain way to being completely compassionate and trying to help him develop those skills.Laura: Wow.Emily: I say completely, but I'm still human.Laura: Yeah.Emily: I still mess up. I still go back to like, "Why are you doing this?" Pulling my hair out, OK I'm gonna pause. He's doing his best. And what is going on? instead of this like, "What is my child doing?" It's like, "Huh, what is my child doing?" Moving from judging my own child to curiosity, that's helped me, and then realizing other people might be judging me. And they might not be. And it's OK. Like I can be a good mom, even if they're judging me.Laura: A lot of what you just described is the reason that I just went back to therapy. I'm not kidding. I recently went back to therapy just to cope with like, "How am I reacting to my kids? How can I change my mindset about things that bother me, etc." I'm wondering if you could maybe call out a few of the areas where it's tricky to unravel what is a gifted type behavior versus an ADHD behavior. If it's helpful to start you off, I heard you talking about boredom. And from what I know from our experts that we work with, I know that boredom can be a big factor for gifted kids. But boredom is also something that a lot of kids with ADHD struggle with. So, talk to me about symptoms.Emily: I feel like there is a lot of crossover. I've never actually thought about separating them. For my son and for me, we don't see our ADHD as like a debilitating or a disability. We see it as a superpower. Because, and that's actually what I thought was going on. His mind was just always going so fast, and that helped him learn things really quickly and it helped him understand and it helped him come up with these ideas. But it also leads to like acting really fast and you can't wait your turn to speak. You just have to blurt out your answer right now because it's fresh on your mind and you can't wait to share it and interrupting conversations, acting without thinking. I always thought it was just the super-fast brain.But a lot of things like impulsivity is a symptom of ADHD. And I'm like, "But being spontaneous," that's what we always call it, "is really fun and it can be really creative," right? So, is that the giftedness, or is that what most people think is ADHD actually having a good spin on the same symptom?Laura: How does Jack identify? Does he use terms like 2e year or twice exceptional, gifted, ADHD, or just not a thing for him?Emily: It's not really a thing for him. Once in a while, he'll say, "Hey Mom, so I was at school..." and stop mid-sentence, and then he'll come back and say, "Is that because I have ADHD?" Like, he's asking why he just stopped mid-sentence.Laura: Wow. Good for him. I love that curiosity.Emily: And so, we approach it from like, "Yeah, it's likely and it's OK, right? And so, we were totally accepting of it in our house. And rather than, "Oh, that's what's wrong with me," we use it as, "Oh, that explains that quirk."Laura: So, let's talk about your "aha" moment, Emily. When you were going through the evaluation process with Jack, which symptoms stuck out to you? Which symptoms in particular that really spoke to you and who you are as a person?Emily: There are a lot. I think interrupting was an obvious one. When I was first married, I would interrupt my husband a lot to the point where he thought I just didn't care what he was talking about and he thought I didn't care about anything he had to say. And that wasn't it at all. I cared a lot. It was just like the thought came into my head in my mouth opened up, and I didn't realize I was doing it until he stopped me. One day he was like, "Do you realize you just interrupted me like five times in this conversation? You didn't let me finish my sentence." And I stopped and was like, "Oh, really? And why am I doing that?" I was like, "Oh, OK. Well, that's one of my quirks."When I was younger, I did really well in school, but in college, for example, I thought everybody had the same struggles I did with sitting down and reading a textbook. I had to go to the gym to read a textbook. I had to get on a treadmill and walk or ride a bike, or I had to find an empty classroom and stand at a podium and read it out loud or pace around the classroom while reading it out loud, just to get myself to focus on it. So, I did really well in school, and I thought everyone had those struggles. And I honestly, I was graduated, and I was dating my husband, who was still in school, and we sat down — I sat down to grade papers. I was a teacher at the time — and he just put out this super boring history textbook and he sat there, and he read it, and he was turning pages. And I said, "Are you actually like paying attention to that?" He was like, "Yeah." I'm like, "No, like, you didn't have to go back and reread that first page six times?" And he was like, "No, I'm just reading it and paying attention."Laura: Oh my God. It boggles the mind. I mean, for sure I can't. I see people do that too, and I'm like, "What are you doing? Aren't you like, how are you just not moving around?"Emily: Yeah, he wasn't like twitching in his leg or like flipping a highlighter lit or like anything that I do to cope. And I was in my early twenties and was like, "Wait, that's possible? I really thought everyone struggled to read something boring like that."Laura: What about impulsivity? You mentioned that Jack has struggled with some impulsivity or some spontaneity. He has the luxury of being spontaneous. What about you?Emily: Oh, yeah. I'm a teacher and a mom, and it makes for a really fun teacher role. I'll just be sitting with the kids and be like, "You know what, kids? Let's go on a turkey hunt." And we had nothing to do with the lesson plan, but I just looked at the kids and they were fidgeting and the idea pops in my head and suddenly we're acting out a turkey hunt in the classroom and it's so much fun. But I do have to temper it because we want to be wise with that.It's easier as an adult. I think as a child, when my upper brain wasn't fully developed, it was my classic example. I was five or six and I was at my grandma's house visiting her. She had this beautiful — it was probably a handmade doily — on one of her end tables, and there was someone had set a pair of scissors on it. You already know what happened.Laura: Oh, my God.Emily: I didn't even think, I was just like, "I wonder what it's like to cut through that doily." And so, I picked up the scissors and I just cut right through. I don't even know if I cut through it. I just remember cutting it and feeling I was just curious to know the texture of when the scissors went through it. I honestly wasn't trying to be bad. I didn't even think it through. I was just like, "I wonder what it's like to cut through that doily." And I try to remind myself of that when my kids do things that I'm like, "What in the world are you doing?" And like, they probably weren't thinking. They probably just had a thought pop into their head, and they acted on it.Laura: Oh, my gosh. Emily, this is reminding me of something. When I was a kid, I remember that I didn't feel like I had enough shelves in my room, so I just went in, got some shoeboxes and some super glue, and I glued them up to the wall. And they were obviously, they were not perfectly straight either, so they were tilted, so the shelves didn't really work, but I just super glued a bunch of shoeboxes to the wall, and I was like, "Why are Mom and Dad so mad?"Emily: I think that's incredibly creative, which I feel like people with ADHD are incredibly creative. We have these out-of-the-box thoughts who would think to go and grab shoeboxes and super glue it into the wall? Like we could say that negatively, like “Who would ever think to do this?" But we can also think, "Oh my goodness, that is brilliant." You saw a need in your room and you just went for it and you totally thought of a solution that nobody else would have thought of. That's incredible.Laura: Thank you, Emily. And that's very, that's very validating. I appreciate it. Can you call my parents after we record?Laura: Has your son getting diagnosed with ADHD and now you knowing that you have ADHD, has that created a unique bond in any way? Is that brought you closer together? It sounds like you've always been close, but just curious.Emily: Yeah, it's helped me be a lot more empathetic, like where I realized, "Well, I wasn't trying to interrupt my husband," and when he interrupts me, I'm like, "He's not trying to do this. It just kind of that that in his head, in his mouth opened up."Laura: Right.Emily: I'll say something like, "This is our superpower." And his little brother was recently diagnosed with ADHD also. And I'm a little bit suspicious that the third one might have it, but he's not quite old enough yet for us to get him evaluated. And so, yeah, I just, my poor neurotypical husband, he never understands why we're like so creative and so spontaneous and just...Laura: I bet he loves it. That's got to be really exciting, right?Emily: He does, I mean, he married me for a reason, right?Laura: That's a lot of spice of life that you're going to have that you already have in your house.Emily: It is.Laura: You're like "It is, I'm tired."Emily: It's fun. It's fun. I really, I mean, I wouldn't want my kids any other way, but it is a lot of work. Yeah, it really the hardest has been the emotional dysregulation part of it that I had to learn to temper myself. I would just flip a switch and get angry so fast when they were doing something that I thought that they shouldn't and learning to catch myself before I get to that ten.Laura: That is so hard. I find that to be the most difficult thing about parenting. You know, I'll be fine, fine, fine, fine, fine, being a quote-unquote model mom, and I'm just I'm responding calmly to things and gently nudging and teachable moments. And then I just get to this point and I'm just like, "Just go to bed," and I just want to lose it. I'm like, "You got to get out of here. I can't answer this question again." And the way I just said it, it's putting it mildly. So, I feel you and I'm working on it. It's a journey.Emily: We're all working on. It sounds like you're human. Isn't that great?Laura: Thank you.Emily: And we were talking about like ADHD being a superpower. A lot of things list oversharing as a part of ADHD, and I was a little bit mind blown when I read that because I was like, "I've always called it being authentic." And I realized a lot of my really close friends also have ADHD, and a lot of us didn't know until we were in adulthood. And I realized like I was being authentic, they were being authentic.Maybe people were a little bit weirded out because they called it oversharing, but we connected with each other and just felt like we were totally open. And when people come to know me, they know the real me. I can't hide it very well. It's just who I am. And so that it's another spin on "Sure, you might be able to call it oversharing," but for me, I'm like, "I'm just telling it how it is, and now you know who I really am."Laura: You are so good at spinning this. So, I'm going to run down what I've heard so far, and then I may ask for more. So, oversharing, reframing that as authentic. Impulsive, reframing that as spontaneous. Can I try out a few more on you and see what you come back with?Emily: Sure, let's.Laura: Hyperactivity. Hyperactive.Emily: Energetic.Laura: Yeah. Distracted.Emily: Overly attentive.Laura: Oh, this is great. You're so good at this. Let me think. How about disorganized?Emily: I'm still struggling with that one.Laura: Creative.Emily: Human.Laura: Human, there you go. Forgetful.Emily: Oh, learning to use tools. Using a phone alarm all day long.Laura: Got it. Oh, my gosh, procrastinating.Emily: Oh, yeah. You're hitting some of my pain points right now.Laura: Sorry.Emily: Yeah, I don't have a creative spin on that one.Laura: So, you've learned to flip the ones that are primarily maybe your kid's symptoms, but tougher when it's things that are more about us.Emily: Well, yeah, I think just learning to flip the ones that I really do see as being able to be helpful. I can't, procrastinating is just one of those hard things we have to learn to find ways to deal with it, I guess.Laura: That was really good. I'm really impressed with your ability to do that. It's just like you really, your mindset is really lovely.Emily: Thank you.Laura: What's one or two things that you wish more people understood about ADHD?Emily: I think the biggest thing is that people with ADHD are really doing their best, that we're not interrupting you because we don't care about you. I guess that's the biggest one. People with ADHD are doing their best and that might look different than someone's best that doesn't have ADHD, but it doesn't mean that the efforts are not there still. And in fact, many times we're trying two or three times as much to do the same thing.Laura: Tell our listeners about your podcast.Emily: As you said, it's called "Enlightening Motherhood," and our goal is to help moms who are feeling overwhelmed with their children's big emotions, which often lead to big behaviors, too. And it's meant to help empower them so that we can turn that overwhelm to confidence so that they can confidently parent their children. It starts with us with our mindsets, with being able to handle those difficulties, and then we learn a lot of tools that we can apply to parenting.Laura: Emily, it's been so great to talk with you today. Thank you so much for doing this and just for your candor.Emily: Thank you. Thank you so much for having me. And I love the work you're doing with this podcast and with Understood. I love to follow you on Instagram and just the compassion that you have for not only people that are neurodivergent, but also trying to get the information out there in the world so that we can all understand each other a little bit more. I just love your mission and what you're standing for.Laura: Oh, thank you so much. You've been listening to "ADHD Aha!" from the Understood Podcast Network. If you want to share your own "aha" moment, email us at ADHDAha@understood.org. I'd love to hear from you.If you want to learn more about the topics we covered today, check out the show notes for this episode. We include more resources as well as links to anything we mentioned in the episode. Understood is a nonprofit organization dedicated to helping people who learn and think differently discover their potential and thrive. We have no affiliation with pharmaceutical companies. Learn more at Understood.org/mission. "ADHD Aha!" is produced by Jessamine Molli. Say hi, Jessamine!Jessamine: Hi everyone.Laura: Briana Berry is our production director. Our theme music was written by Justin D. Wright, who also mixes the show. For the Understood Podcast Network, Scott Cocchiere is our creative director, Seth Melnick is our executive producer, and I'm your host, Laura Key. Thanks so much for listening.

12 questions to ask the school about 2e students

What do you need to know about how your child’s school supports gifted students with learning and thinking differences? One key question is whether the school is aware of the Department of Education’s guidance around supporting twice-exceptional (2e) learners.See a list of other questions to ask the school below. You can print this list by clicking the view or download link below.How do you define a gifted and talented student?When are students screened for gifted and talented identification? What measures do you use?Do you have a specific program for twice-exceptional (2e) students?What type of instruction do you offer for 2e learners?Do you have teachers with training in teaching children like mine?What enrichment activities do you offer for gifted students?Do 2e students typically receive accommodations through an IEP or a 504 plan?How do you offer emotional support to 2e students?What support do you provide for kids who are thriving in some areas and struggling in others?How do you propose to use my child’s strengths to work on challenges?Do you have any resources to help me learn more about how you support 2e students?How can I help you better understand my child?Explore common myths about 2e students. And read about a parent’s unique IEP solution for his 2e son.

The Opportunity Gap

The Opportunity GapTwice-exceptional Black and brown kids

Kids who have learning and thinking differences can also be gifted. But what does being “twice exceptional” mean when you’re marginalized?Kids who have learning and thinking differences or other disabilities can also be gifted. This is known as being “twice exceptional,” or “2e.” But what does twice exceptional mean for Black and brown kids? In this episode, hosts Julian Saavedra and Marissa Wallace explore how kids who struggle with learning can also have incredible talents and skills. But for marginalized kids, these abilities are often overlooked. Gifted testing may be biased against them. The hosts react to startling statistics about how few kids of color are in gifted programs. Listen for thoughts and advice on how families can get schools to focus on their kids’ exceptional abilities, not just their challenges.Related resourcesGifted children’s challenges with learning and thinking differences12 questions to ask your school about 2e studentsWhen gifted kids need accommodations, too (In It podcast episode)National Center for Education StatisticsPublic school gifted or 2e programs mentioned in this episode:Montgomery County Public Schools twice exceptional students and servicesChicago’s U-46 gifted and talented academy (in process of renaming) Aurora Public Schools definition of gifted and talentedArizona Public Media news article on Southwest Junior HighEpisode transcriptJulian: Welcome to "The Opportunity Gap," a podcast for families of kids of color who learn and think differently. We explore issues of privilege, race, and identity. And our goal is to help you advocate for your child. I'm Julian Saavedra.Marissa: And I'm Marissa Wallace. Julian and I worked together for years as teachers in a public charter school in Philadelphia, where we saw opportunity gaps firsthand.Julian: And we're both parents of kids of color. So this is personal to us.Welcome back to "The Opportunity Gap." What's up, Marissa?Marissa: Good to be back. How are you doing, Julian?Julian: I've got to take a deep breath. If I'm being honest.Marissa: We can do that.Julian: Today was a day. Today was a day. You know, tomorrow's a new day, so we start fresh tomorrow and we see where it goes.Marissa: And it's Friday tomorrow.Julian: It is Friday. Fri-yay!Marissa: And Lincoln's birthday! We have a 6-year-old in our house tomorrow, so that's happening.Julian: Oh, snap, OK. What are you going to do for the little guy?Marissa: He's actually going to have a dance party. So he's having a hip-hop-themed dance party.Julian: Well, hopefully his dad is not going to be teaching him how to dance. Because I've seen that man try to get on the floor and he just needs to sit down, take a seat.Marissa: Lincoln's got it.Julian: Lincoln will dance circles around him. I'm sure he'll do the wobble and everything else. So, I'm actually pretty hyped about today's episode because it really is hitting at the intersection of a lot of the things that we've been talking about. And so I want to really dig in and dive in to the idea that there's so many exceptional students out there. So many students that have gifted possibilities. So many students that also have learning disabilities and learning and thinking differences. And so many of them that are Black and brown students that are not being given the services that they deserve.So let's go into Julian as a teacher. Back in the day, I was the history teacher, and I was definitely a popular teacher and the kids liked me. But I also knew that there was a lot of things I didn't know about how to teach, especially when it came to students with learning and thinking differences. And I remember this one student, his parents were immigrants. They were refugees. They had come from Central America, and neither one of them spoke English. But he had learned English on his own, and he was kind of a quiet, brooding type. He'd kind of chill in the back, not really talk too much. But he had been identified as having a learning disability. And so a lot of his teachers thought that he didn't really want to be engaged with the activity. He'd never acted out or anything. He just kind of just sat there and didn't really do much. So this one in particular, though, because I taught history, for some reason, it sparked an interest in him.And so, when he came to my class, we would have these crazy-deep conversations about his thoughts on history. When I taught about World War II, he had such an in-depth knowledge of Nazism and of the Allied forces. He could name every single general on the Allied side, with the correct pronunciation for the French generals. He could name the different battles. He could tell me every single type of airplane, the B-52s, and all of the things that were involved in this war. And I found out that he had gone home and memorized everything. And I'm sitting there like, "Bro, you've been sitting in the back of this class for the last, like, three months, not saying a word. And then out of nowhere, you come out and have all of these facts. Where does this come from?"So, as I got to know him more, I've found that the learning disability manifests itself in his struggle to stay focused in the moment. But if he found something that interested him, he was completely bought in. And so we worked together with him and some other male teachers, kind of got together and really tried to push him to show what he really knew. And over time we found out that he really loved writing, he really loved history, and he loved to write about his experiences. He graduated eighth grade, he went on to high school, he went to college, and he has just finished writing his first book.Marissa: Wow.Julian: And he is going to different places around the world to learn more about the history so that he can write about them. He actually participated in Bernie Sanders' campaign. And one of the coolest pictures that I've ever seen is this student in the back with the Bern, hanging out with him during this campaign. And I'm thinking back to when he was an eighth grader, sitting in the back of my class, telling me about World War II and Allies and communism and Nazism, and here he is, working with this man that is in big-time politics. And it makes me think, "Why did we never test him to see if he was gifted?"Marissa: Absolutely. Thank you, Julian, for sharing that story. I think it's really a fantastic way to start this conversation. If I think back to 12 years ago and where I was as an educator, I don't think I was able to navigate students who had this twice exceptionality.Before we really get in, let's talk a little bit first and foremost about some of these definitions, right? So, when we're talking about twice-exceptional kids, understanding first, this idea of gifted, right? So what gifted is, is this exceptional talent or a natural ability compared to others, right? So, if we look at, like, you know, what's considered average, these are individuals who perform above average compared to their peers and their experiences, their environments. They're performing above average. So, a child or individual who's twice exceptional is a child who also has this gifted ability, this exceptionality, and also a disability. So, some other ways we can think about it, right, is a kid who has learning and thinking differences but also has, like, a really exceptional ability when it comes to their cognitive ability, their processing skills, right?There's, like, natural talent that they have. I know parents, I talked to there's this reference to 2e, if you hear Julia and I interchange and say the word 2e —Julian: It's like a superhero: 2e.Marissa: Twice exceptional. Yes, exactly! Right. I love it. Like, it's such a cool term. I think it's still like, we're breaking through some barriers in this conversation today. But I'd love for us to just keep these terms in mind as we go through the conversation and just give them some power in some shout-outs.So let's just dive in to what does giftedness mean for Black and brown kids? Let's start with that.Julian: I will say that my personal experience is that I have lived as a Black man in this society. I am also Hispanic, but my primary experience has been as a member of the African American community. When I think about students, though, specifically Black and brown all across this country, giftedness is — it's a very unclear topic. Traditionally, giftedness falls into the academic realm. There's a variety of tests that are taken, and those tests relate to an IQ score. And that score is determining whether or not that student is considered gifted because their score puts them so far above what the average IQ tests would be for the average student.So, let's unpack that a little bit. As we know, or maybe you don't know, standardized tests historically have been very biased, from the way that they are written, the questions that they are asking, the background knowledge that they are referencing. And in many cases, the people that are giving the test, all of those things include biases that are oppressive to marginalized communities and specifically the Black and brown kids.The prevalence of those tests and the identification process for students to potentially even be considered gifted also is not nearly as strong in urban communities where many of our Black and brown kids live. It's one of the things that gets cut first, when we talk about schools that are strapped for cash.And so all of that leads to a situation where many of our students are not even being pushed to be considered as being gifted in the academic realm. But on a personal level, I'm also thinking of the idea of this word "exceptionalism." You said when you define "gifted," it's being exceptional. So, for somebody that lives in a society that is already designed to support a specific group of people, on a racial level, for them to exist, just to exist, that, in my view, makes them exceptional. For somebody to have multiple barriers to success, whether it be socioeconomic status, whether it be race, ethnicity, language, documentation or lack thereof, and still to be able to be successful and thrive in that. Doesn't that make them exceptional too?Marissa: We haven't even started to talk about the other ways in which someone can be exceptional. All the creative ways in which someone can show forth art, music, talents that we don't look at either. I think just overall there's like this lack of looking at strength and looking at, and like you said, like, what are we comparing it to? You said it perfectly when you were talking through how these standardized tests and the assessments and what is done to go through the evaluation process to be identified as gifted. It is very biased, and it's just not happening in a lot of schools. Even just talking about the student you were sharing about in the beginning, that kid probably went through K through 12 without being identified for his exceptionality. And clearly he had an exceptional talent that thankfully you saw, but why did it have to take that long?And why did he have to be, like, the kid in the back of the classroom who's withdrawn?Julian: You multiply that by millions of people over decades, and you think about how many of our Black and brown students over decades of being in schools have not been even given a chance to increase their exposure to challenging topics, to show and demonstrate their giftedness.Marissa: So as we're kind of discussing this, Julian, you know, it keeps coming through my mind, like, you know, I know from my research alone that there is this overrepresentation of students in the Black and brown communities that are identified in special education, but an underrepresentation of Black and brown individuals within a gifted identification. So I'm curious, Andrew, what are our statistics in this area?Andrew: We had been talking, right, before this episode about some of the statistics around gifted education and disability. So, I looked it up on the National Center for Education Statistics, and, yeah, there is a disparity. Around 8 percent of white students and 13 percent of Asian American students in public schools are in gifted programs. And then by contrast, it's only about 5 percent of Hispanic students and 4 percent of Black students. It actually gets down even less than that in some years.Julian: Wow. A third for Asian versus Black and Hispanic.Andrew: And on the other side, if you look at kids with IEPs, comparing them by race, you know, again, Black students, 17 percent have IEPs, which is higher than the average of 14 percent of students. So, they're overidentified in special education, underidentified in terms of being part of those gifted programs. Interestingly enough, in those statistics are the underidentification for giftedness, just by a percentage, is actually bigger.Julian: I mean, I just have to let that sit for a second. Hearing those numbers, it always, it always hits home when the data speaks. And the data is speaking to us and saying that clearly what we're saying anecdotally is actually truth.Marissa: Exactly.Julian: What I'm interested in, though, is digging more into the fact that Asian and those who identify as white, the higher prevalence of those students in gifted programs. And wondering what are your thoughts on that? I mean, 13 percent of Asian students in gifted programs, like, that's a really fascinating number given that cohort of students is also a minority in our country.Andrew: As someone who's looked at this issue and is also Asian American, I feel like I can speak to this. So, the Asian American community is very diverse. If you look at Cambodian or Vietnamese Americans, for example, they are underrepresented in gifted programs, while other groups are overrepresented. People tend to lump all Asian Americans together, but there's actually a lot of differences between communities. You know, some groups came to the United States as refugees without any money or resources. Other groups came because they had some specialized skills and were recruited by companies. So, it's really hard to generalize and that's going to impact whether or not a family's kids have the advantages to be able to get into a gifted program or be in the right neighborhood. The other thing I would say is that just because you're in a gifted program, it may not be serving you in the best way. You know, a lot of the Asian American people that I speak to feel like there's not enough identification of Asian American kids for learning differences and ADHD. You know, the feeling is you're Asian American, you must, you're too smart. How do you have this problem? Just work harder.Julian: Well, that that's that model minority myth. And I love that you brought up the diversity within a subgroup.Marissa: Absolutely. Andrew, I appreciate you sharing some of that information and your experiences because it does, like, these statistics, while they're jarring, they're not surprising.Julian: Let's go back to our Black and brown kids' learning and thinking differences, but also gifted, 2e.Marissa: 2e, let's do it.Julian: Marissa, I'd love to hear more about what you've learned in your studies and your dissertation work, and in general, how does this play out?Marissa: The main thing is that in general, 2e students are not receiving appropriate programming across the board. I see that a lot, especially with our Black and brown students, because again, based on kind of the experiences they have within schools, educators are very quick to see a behavior. And that behavior becomes the problem they need to address. Right? So student's withdrawn; student can't sit still; student has outburst, right? They're calling out during class. There's behaviors that are disrupting what they believe an ideal classroom looks like. They must need support or services. So then the process usually starts where they're being evaluated to receive special education services.Now, oftentimes there is an aspect of it that does focus on academics and does focus on cognitive ability. Those tests are also done, correct? Now, I think more recently, we're starting to look at those scores more so than we did in the past and be like, "Oh, wow, like, this child is performing above average cognitively, academically," and then they are receiving that twice-exceptionality — that 2e — identification.What I think is missing, though, is I still feel like their programming is built upon the behaviors. So it was focusing on the disability part more so than actually challenging them. So now you're seeing situations where a highly intelligent kid is being pulled out, right? Or the weakness is being focused on and not the strength. And it's interesting right now, because I'm talking to families. And I don't know if this is, like, a solution, but it may be for some families. What's working? Some of the families that I work with now left brick-and-mortar schools because it was way more challenging, they felt, for their students to get their needs met there. But because of the flexibility of virtual learning and virtual programming, they're noticing their students who are identified as 2e are having some success because we have the power to be like, "Oh, you're an eighth-grade student, but you're performing above grade level in math? Great. Cool. We're going to put you in a geometry class." And so we can do that because they're not going to different classroom. You know what I'm saying? They're just, their schedule just looks different. They're just attending that 10th-grade class while being in eighth grade. I'm not saying virtual learning is the answer, per se, but I'm seeing it as something that some parents are becoming interested in seeing if this is the programming that works best for their child.Julian: I'm thinking just on a practical level, say I'm listening to Andrew, Marissa, and Julian talk about 2e and my child is showing signs that they may very well have exceptional ability, but maybe that child already has an IEP for any sort of learning disability. What do I do? What's my next step?Marissa: Well, one, talk to your student, right? Talk to your team. I always say the IEP team is, like, that first family of people you go to have conversations. And remember the IEP is the individualized education plan for your child. So those would be your first kind of, like, line of defense to start the conversation with. And then you as the parent have the right to be like, "Hey, my kid also needs this."One thing we should definitely go over too, Julian, is like the idea of a gifted IEP. Because I think even though it's not a federal mandate to have a gifted program, there are states, district, schools that do that and do it well. And so the parents have to know how to ask for those things to be put in place for your student.Julian: Anybody out there that's listening along with us — families, caretakers, guardians, friends, students, anybody. I mean, thinking about the letters IEP, there's a weight with those letters. There's a weight with that acronym. And sometimes that weight steers to a negative connotation — that it means something's wrong with you, so you need help, right? Like, "I have an IEP. That means that I need to get extra services because something's not clicking right." Let me be the one to tell you you're wrong. And if you think that's what an IEP only is about, you're wrong. An IEP is an individualized education program. It say things that people are going to do as a team to help the student be in an environment that is going to support them to get to the best possible potential.So, the idea that it's just weaknesses, the idea that it's just going to focus on things that are wrong? No. Don't think that at all, especially for my folks that are students of color, my folks that have already dealt with things that have happened in schools that might not be so great. I understand completely. I've worked in schools for a while, and I know that sometimes we are not treated the way that we deserve to be treated. We got to reframe that. We have to change that and realize that this is a place to be empowered. Having an IEP, especially, pushing the school to figure out what are they going to do for your child if they are gifted?Marissa: And that's the stepping stone.Julian: You got to go in there and ask questions.Marissa: Like, use it as a benefit. That's my push, it's like, regardless of how you got the IEP, right? If your child has the IEP and you feel that there's something missing and you feel they have an exceptionality, use that as that stepping stone, because it is a legal document. So, regardless of whether or not your particular school has a gifted program, like, utilize that to be able to then say, "Hey, like in addition to this particular accommodation or specially designed instruction to help my student with this behavior, can we also put in this extension or this activity or something that can also challenge them and meet their needs academically, as well?"Julian: I will say that I'm excited to be in the school district that I live in, where my own children attend. There is a pretty robust gifted program.Marissa: That's awesome.Julian: And what I've found out is that not only are all students eligible, they do a mandatory gifted screening for everybody. And when this gifted screening happens, if a student has an IEP or learning and thinking differences, any sort of assessments are also in place for the gifted screening. It makes sure that everybody has an even playing field. This program that I see these kids doing robotics and taking Legos and making these really cool structures, and they're going out and doing project-based learning.Marissa: And that's what it's all about. That's amazing.Julian: And the district I'm in, it's incredibly diverse. You have Black kids, white kids, Asian, everybody kind of coming together in these groups and really doing some big, powerful things.Marissa: You found the unicorn, Julian. You found the unicorn school district.Julian: I mean, it's not the unicorn, but it definitely is, well, this, I mean, we talked about earlier, like it's not something that should be a unicorn.Marissa: Exactly.Julian: And not to say that the district is perfect by any stretch of the imagination. And Andrew has found examples of powerful things happening all across the country. So trust and believe, like, it's not only one place, outside of Philadelphia, that's happening. Like, it's all over the country.Marissa: Thank goodness.Andrew: There seem to be roses everywhere from all these different cracks, to borrow your analogy, Julian.Julian: Is somebody listening to Tupac?Marissa: Or listening to our podcast.Andrew: Again, right before we started recording, we did some research just to see, like, where are people doing some interesting things around both gifted programs for kids but also twice-exceptional programs. And there were some really interesting ones. I mean, you just mentioned the universal screening. So, Montgomery County public school district, in Maryland, they actually had some criticism over the years because their gifted programs are very slanted toward white kids. And they really made this effort to do the universal screening, as you mentioned. So, instead of just like you apply to the gifted program, they said, "No, we're not doing that. Every kid, we're going to see if they're gifted. And not only that — we're going to match them up with whatever the screening processes they have for disabilities for learning and thinking differences." And that's not perfect, but that's made some differences there, which I think are pretty cool.Chicago School District U-46 was really interesting because a lot of people say that they really prove that these gifted programs could be diverse and that they could integrate them. And that was a really cool thing to see. And Colorado — in Aurora Public Schools, what they did was they used different measures. So, you guys talked at the beginning about sort of having IQ tests that have been traditionally biased. Instead, they looked at all the different tests they were giving and they sort of applied them in different ways to make sure that their programs were diverse, were integrated, were not just slanted toward one group or another, but really captured everybody who is gifted.Julian: Oh, I love that. I love that it seems like they took theory to practice. I mean, the word "equity" and "anti-racism" has been the punchline of the year, but I love that I'm hearing about actual tangible changes that are benefiting everybody. And it seems like these programs you're talking about are exactly it, it's theory to practice. So, that's dope.Andrew: Let me share one more that I thought was really cool was in Yuma, Arizona. So, Southwest Junior High — and there's a center at Johns Hopkins for, like, talented youth, and they always identify the top 10 junior highs in the country, and they identified Southwest Junior High, near the Mexican-American border, which has a really great gifted program. And the demographics of that school are heavily Hispanic, a lot of immigrant families. So it was just cool to see that happening and to give, like, real concrete stuff. We'll put some links to these programs in the show notes. I'm sure if people dig in, there's always drawbacks, but it's still great to see some of these things happening.Marissa: There's no perfect scenario yet, right, that we know of, but at least there are educational systems that are taking steps in the right direction to do better.Julian: So, we just touched the tip of the iceberg. Just the tip of the iceberg. You know, anybody out there that is choosing to listen to us first, we appreciate it. We want to hear from you. We want to hear what you'd like us to discuss. What topics are you interested in? What things should we lift up specifically around the opportunity gap?You can always reach us at opportunitygap@understood.org. You can call Andrew; he's giving his personal number at the job.Andrew: That's actually the show voicemail.Julian: Just kidding, just kidding. 646-616-1213, extension 705. Again.Marissa: As parents, as educators, like, Julian and I have spent literally over a decade having these conversations, and so we know how meaningful it is for us to discuss some of these topics. So hearing your thoughts, and especially as we dig into something where it may be a new term, this 2e, this twice exceptionality, and we want to know if you have had experiences of success within your own families.Julian: Please, feel empowered to go to your schools or go to whomever you're dealing with in the educational pathways. What are they doing to help address giftedness? Are there programs out there? What is the gifted program availability? What does the screener look like? What ways are they challenging? Even if your student is not deemed to be gifted, they still deserve to be challenged, and they still deserve to have extra activities to meet their needs. Feel empowered to go in and ask.Julian: This has been "The Opportunity Gap," a part of the Understood Podcast Network. You can listen and subscribe to "The Opportunity Gap" on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.Marissa: If you found what you hear today valuable, please share the podcast. "The Opportunity Gap" is for you. We want to hear your voice.Go to u.org/opportunitygap to find resources from every episode. That's the letter U, as in Understood, dot O R G slash opportunity gap.Julian: Do you have something you'd like to say about the issues we discussed on this podcast? Email us at opportunitygap@understood.org. We'd love to share and react to your thoughts about "The Opportunity Gap."Marissa: As a nonprofit and social impact organization, Understood relies on the help of listeners like you to create podcasts like this one, to reach and support more people in more places. We have an ambitious mission to shape the world for difference. And we welcome you to join us in achieving our goals. Learn more at understood.org/mission. "The Opportunity Gap" is produced by Andrew Lee and Justin D. Wright, who also wrote our theme song. Laura Key is our editorial director at Understood. Scott Cocchiere is our creative director. Seth Melnick and Briana Berry are our production directors.Julian: Thanks again for listening.

How the documentary “2e: Twice Exceptional” made me a more hopeful parent

I’m always wary of telling people my sons are twice exceptional, or 2e. It means they’re intellectually gifted and have learning differences. I could explain this to people. But I worry they’ll stop listening after I say “gifted.”Sometimes I feel like people think one “E” makes up for the other “E.” As if the gifted part cancels out all the learning challenges. The truth, however, is the two multiply and make my kids twice as complicated.People don’t always understand that I’m also twice as worried about them. I cry behind closed doors because I don’t want other people to tell me I should be grateful they’re gifted. In my mind, those gifts make them stand out twice as much.But when I watched the new documentary 2e: Twice Exceptional, I couldn’t hold back. I cried openly with tears of relief and recognition. Here’s the trailer for the film.The film follows a small class of students at Bridges Academy, a school in California for 2e students. The film weaves together stories from students, parents and teachers about the joy and challenge of teaching these kids.I was in awe — the students in the film are so much like my sons!I laughed hearing the kids in the movie say things like: “You tell me to look you in the eye and I want to know which eye should I look in!” That’s just like my sons. They have no problem reading books, but reading social cues is tough.I was also struck by the knowledge of the school staff profiled in the film. One psychologist explained how kids who are way ahead intellectually may be way behind socially. That disparity, she explained, can cause great anxiety.“Yes!” I said to myself, when she talked about how these kids tend to disregard their talents because of their challenges.The film shows that when you work at reaching 2e kids by building on their strengths, they really can soar.In one scene, a student asked offbeat questions about the geography of the places in The Great Gatsby. His teachers realized the best way for the student to study the book was to literally create a map. Once he created the map, he became more invested in the characters and the literary themes.I also deeply identified with the parents in the film. I knew exactly what one mother meant when she said she thought her son would be at home forever. She didn’t know if he would go to college or get a job. Like her, I worry that my oldest son might not be able to handle the “real” world. I celebrated with her as I watched her son blossom throughout the film.For me, the most moving part was when one of the school’s teachers spoke about happiness. He said:Happiness is just this kind of trill that happens in the melody. Like, there’s the melody of your life and then every once in a while, there’s a little trill, a little something extra. And that’s what happiness is ... except if you’re not singing the song, you’re not gonna get the trill anyway. So you gotta sing the song.As parents, I think we need to encourage our kids to sing their song. That’s how they can find their happiness — the trill in the melody. But we also need to sing our own song. All my worrying about my sons can dampen my happiness, but this documentary is a trill in the melody for a parent of 2e kids.The film reminds me that there are more kids out there like mine than I might think. It shows me there are people who understand them and will accept them for their gifts and their challenges. And that gives me so much hope.Do you have 2e children? Learn more about their rights in school. And explore questions to ask the school about meeting their unique needs.

ADHD Aha!

ADHD Aha!ADHD and hormones (Catie Osborn’s story)