89 results for: "speech%20therapy"

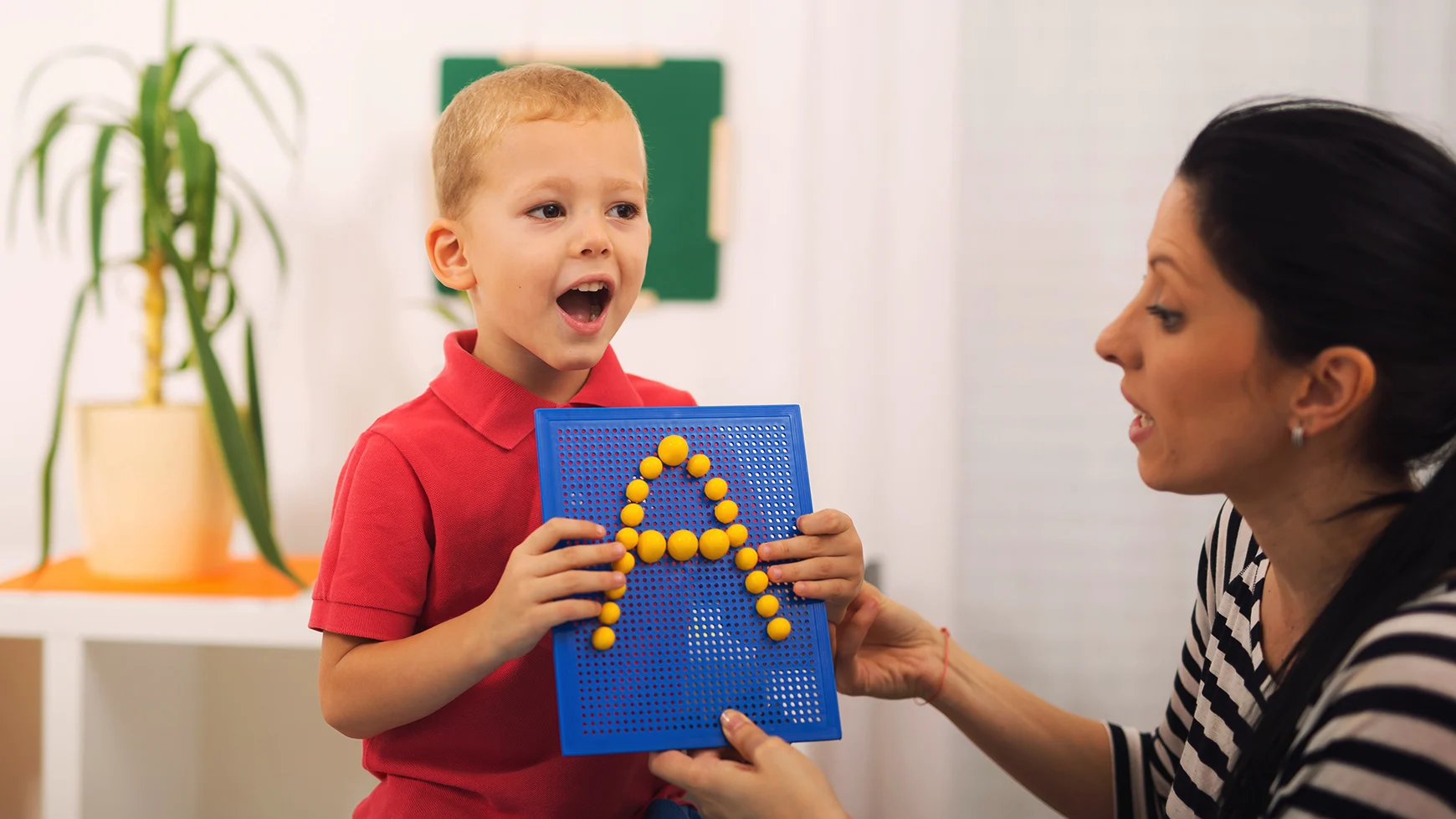

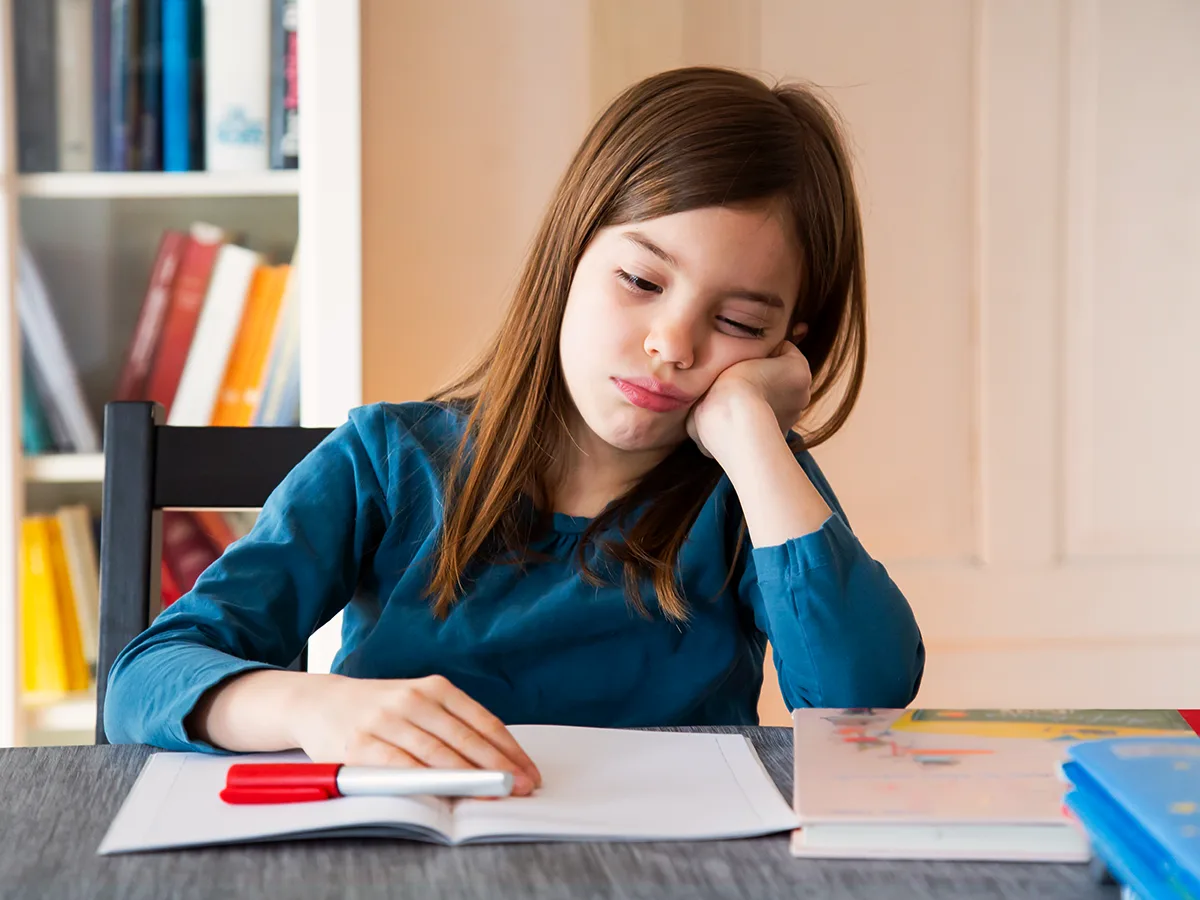

Speech therapy: What it is and how it helps with language challenges

Speech therapy is a treatment that can help improve communication skills. It’s sometimes called speech-language therapy. Many people think that speech therapy is only for kids with speech disorders that affect pronunciation. But it can also target problems with:Receptive language (understanding language)Expressive language (using language)Social communication (using language in socially appropriate ways)Reading and spelling (including dyslexia)Here’s more about speech therapy and how it can help kids with language challenges.

Understood Explains Season 1

Understood Explains Season 1What happens after an evaluation for special education

The evaluation report is done. Now what? Learn about eligibility determination meetings and different kinds of supports for struggling students. Adverse impact. Eligibility determination. IEPs. 504 plans. What are these things? And what do they have to do with evaluations? This episode of Understood Explains covers how school evaluation teams decide which kids need which kinds of support.Host Dr. Andy Kahn is a psychologist who has spent nearly 20 years evaluating kids for public and private schools. His first guest on this episode is special education teacher Lauren Jewett. They’ll explain:What happens at an eligibility determination meetingHow schools decide who qualifies for an Individualized Education Program (IEP) What other kinds of support can help struggling studentsAndy’s second guest is parenting expert Amanda Morin. They’ll share tips on what to say to your child after an eligibility meeting — and what not to say.Related resourcesWhat to expect at an IEP eligibility meetingThe 13 disability categories under IDEAThe difference between IEPs and 504 plans10 smart responses when the school cuts or denies servicesParent training centers: A free resource in your stateEpisode transcriptLeslie: Hi, I'm Leslie from Little Rock, Arkansas. In second grade, within the first couple of weeks, it was decided by these evaluations that Sarah needed speech therapy, occupational therapy, and I think physical therapy. She wasn't holding her pencil right, she had her wrist turned the wrong way, she had some speech impediments. And then we would receive the results of that and eventually she reached her milestone and those kind of fell away. But she did always receive accommodations for reading and math, and that was evaluated every semester. And that IEP followed her from second grade until she graduated from Central High School with a 3.5 grade point average that last semester.Andy: From the Understood Podcast Network, this is "Understood Explains." You're listening to Season 1, where we explain evaluations for special education. Over 10 episodes, we cover the ins and outs of the process that school districts use to evaluate children for special education services. My name is Andy Kahn, and I'm a licensed psychologist and an in-house expert and understood.org. I've spent nearly 20 years evaluating kids for both public and private schools, I'll be your host.Today's episode is about what happens after the evaluation. All the testing and data collection is done, the evaluation report is done. The next step is a real mouthful; it's called eligibility determination. This is when the evaluation team meets to decide if the student is eligible for special education. Today's episode is going to cover three key things: how the eligibility determination process works, what kind of supports schools offer to students — including what's available to kids who don't qualify for special education — and what to say to your child after an eligibility meeting, and what not to say. But first, let's hear another parent story.Jennifer: Hi, my name is Jennifer and I live in Atlanta, Georgia. So, in the eligibility report, they enter all of the testing information into this program, and it automatically determines which categories the student could potentially qualify under. And so, one of those categories for my son was like, brain something, I can't remember. I wish I could remember what it was called. But it was something that was like crazy. And I was like, "Wait a minute, what?" It's just that even in the meeting, they'll tell you, you know, "This is automated, and just because it like flags it doesn't mean that we're really considering it, but we do have to talk through it."Andy: What Jennifer was just describing can be a jarring part of the eligibility determination meeting. This is the part of the meeting when the team goes through a dozen or so disability categories to see if the child qualifies for special education under any of them. And folks, just so you know, the name of the category that Jennifer was trying to remember is called traumatic brain injury. We're going to talk more about the disability categories and other key parts of the eligibility determination process.To help me explain all this, I want to bring in my first guest. Lauren Jewett is a special education teacher at an elementary school in New Orleans. She's also a special education case manager, which means she's been a part of a lot of evaluation teams. She's also a national board-certified teacher, and an Understood teacher fellow. Lauren, it's so great to have you here with us today. How're you doing?Lauren: I'm good. Thank you for having me on this show.Andy: So, Lauren, after an evaluation, the school team holds an important meeting called eligibility determination. This is where the team uses the evaluation report to help decide if the student qualifies for special education. So, if the student qualifies, then the next step is to develop an IEP, which stands for Individualized Education Program. So, this part of the process, determining eligibility for special education and then developing an IEP, this is all covered under IDEA. Lauren, can you remind everyone what IDEA stands for?Lauren: IDEA is the federal special education law that stands for the Individuals with Disabilities and Education Act. And it covers all the ways that a student would get into special education for their servicing, and all the different disability categories that they could qualify under. And then after the evaluation period or process, what they could get, you know, in terms of an IEP and what that looks like and all the legal procedures with the student.Andy: Gotcha. So, all states have to follow this federal law, but, you know, different states may handle eligibility determination in slightly different ways. I'm located in the state of Maine. So, in Maine, we determine eligibility, and we actually use a very specific form for eligibility determination, so we use what we call an adverse impact form. The purpose, really, is to see whether someone is eligible or not for services, based on all of the data that we have. We use our adverse impact form and we go through a series of checklists. But in different states, it's done in different ways. How do you guys do that in Louisiana?Lauren: So, our process is covered by a state bulletin; we have a state bulletin called Bulletin 1508, and Bulletin 1508 covers all of the ways that people appraisal and the school psychologists can qualify a student for the different disability categories. So, IDEA, which we talked about, that law has a bunch of different disability categories. And so that bulletin, 1508, outlines all of the different procedures that one would have to look at and use to determine what category or what classification the student would qualify under.Andy: OK, so taking a look at the big picture, you're talking about state regulations that make the evaluation team fill out checklists and answer very specific questions. And you have to do all this to determine if a child meets the IDEA’s two most important requirements to be eligible for special education. Number one, the child has to have a disabling condition, and number two, that disabling condition must adversely impact the child's education. So, when we talk about adverse impact, like an example, let's say we're looking at a specific learning disability, if a child was let's say, half a grade level behind, would that typically be adverse impact, or would that not be enough?Lauren: We usually, you know, if I'm thinking for an example of like, specific learning disability, you know, in our state, in order to qualify for a specific learning disability, there has to be an area of strength, and then an area where the student is, you know, struggling. And then they look at standard deviations below a mean, or above a mean.Andy: OK, so I'm going to decode some of this information. Because again, it's really, really helpful. When we talk about things like standard deviations, what we're talking about is, when you're comparing a child's piece of information to a large group, and how far they fall from that large group, if it's far enough away, that would be something that might be considered adverse impact, meaning adverse impact really refers to is the child able to do what they're needing to do, like other students of their age or grade level? The adverse impact would be "I can't do this because I have dyslexia," or they can't focus and engage and participate in a way that would be manageable for them because of severe ADHD or some other disabling condition. So adverse impact's really about there's a functional thing that isn't happening. You could have a diagnosis, but not necessarily show adverse impacts. And that can be confusing for people. How do you go about explaining adverse impact to your families if you're talking to them about that?Lauren: Yeah, I think when I'm thinking about adverse impact — especially when I look to write IEPs, right? — we think about a disability impact statement, which is kind of similar, you know, like, how is the disability impacting the student in class? So, for example, if the student has dyslexia, how is that affecting what they're doing in class across different subjects all day? So, if the student has a specific learning disability in reading, and they are two to three grade levels behind, thinking about, OK, this is the student's disability, this affects their ability to read on grade level texts that are going to be provided to them and given to them in class. So not just in reading class, but in all those content areas that have a lot of academic domain vocabulary, a lot of reading comprehension needs.And so, when I break that down, I'm trying to give more applicable information to a family, you know, because again, there's so much jargon. So then let's, like I say, let's take a step back and look at how is this going to look like in the classroom? How is this affecting them on a day-to-day basis?Andy: Gotcha. So really, adverse impact is important because you're talking about the how, right? How do we know that this child isn't doing as well as we hoped that they would do because of this disabling condition? OK, and that's really important for families. So, when we talk about the information being considered, who's typically present at the meetings where you're going over the evaluations and making that eligibility determination?Lauren: It usually would be the school psychologist or educational diagnostician — those are the people who maybe conducted the different set of tests and assessments that were given to the student, or the person, you know, who wrote and did the comprehensive report — you're gonna have the parent there, the parent may have another family member there, maybe an advocate. But you could have a special education coordinator there, the teacher, other members who contributed to the report, or additional teachers. You know, if it's a reevaluation for a student that's already been in special education, then it is likely that the special education teacher may be there because that student has already been receiving services.Andy: That was super helpful, Lauren. When we talk about the disability categories, we traditionally talk about the 13 disability categories in IDEA. I understand that in certain states, we can actually see as many as 14, or even 15 categories. The categories that I most commonly see us use in schools are specific learning disabilities, speech and language impairment, other health impairment, and autism. Less commonly, we might see intellectual disabilities, for example, or deaf-blindness.I'd like to shift our conversation a little bit. So, Lauren, when we have a child who's found eligible for special education services, and they meet those two requirements, they've got their identified disability, they meet the adverse impact, adverse effect criteria, what happens next? Let's assume we're at that next meeting.Lauren: Yeah. So, the next step would be for the IEP team to convene and meet, and look at the information that's been provided in the evaluation, and then create an IEP for the student. So oftentimes, you know, these evaluations are very long. And you know, when I receive those evaluations, I have to read them and go through everything and think about what makes sense for the student. But the main thing in that meeting, the IEP development, is really taking that information from the evaluation, and making sure that it's reflected in the spirit of the document.Andy: Yeah. So, let's pause on that for a minute. You're talking about how you can make sure the IEP reflects what's in the evaluation report. How can parents help with this? Like, what role can parents play in developing the IEP?Lauren: I always encourage families to, you know, as we start those meetings, those IEP meetings, I always say, "There's going to be a lot of information. You know, stop if you have questions." And also like, every page that we go through, whoever is leading that part of the meeting, we have the person who's leading that part, like stop and ask the parent like, ''How does that sound? Do you have input? Do you have anything you want to add?'' You know, it just depends. But I always, you know, tell parents ahead of time to, I explain — especially if it's their first meeting ever — I just say, you know, like, ''Bring your ideas of what you would like to see. What do you hope for your child to get out of this? What are your concerns? What's not currently working?''Andy: So, Lauren, what if the child has a disability, but isn't eligible for special education? What are we gonna do in a situation like that? Because if a child's not getting an IEP, how do you explain that to a parent?Lauren: In that conversation, you know, if they're not going to have an IEP, sometimes we do try to provide supports in the classroom through a 504 plan. So, a 504 plan comes from section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. And that's a civil rights law. So, a 504 plan is more like an accommodation plan that a student might have in the general education class. It's not specially designed instruction, it could be the student gets some extra time when they're doing assignments, it might be specified seating; it doesn't have as many accommodations or modifications listed as an IEP because an IEP is going to be more situated and individualized for the student on their goals.And then it is also allowing, like I said, specially designed instruction modifications, you're not going to see that as much with a 504 plan. A student could have a 504 plan for a short period of time as well. Maybe they break their arm, and they need a scribe or need some different assistance in class for that period of time. So, it could range in different situations. But again, it's different because it's not, you know, listing a bunch of different goals and related services like an IEP would.Andy: At the eligibility determination, is a common outcome that the team decides that the student qualifies for a 504? Or does that happen at a different meeting if they don't qualify for services under IDEA?Lauren: It may be a separate meeting; maybe the team comes together, they go over the evaluation — no exceptionality is found. And so, we talk as a team and say, well, you know, sometimes teachers will be indicating that they still have concerns about the student, and how they're going to be able to do everything in class without certain supports that are formalized. So, you know, maybe their recommendation would be a 504 plan. And so, it could be a separate meeting that happens with maybe not all the same people at the table, but definitely the teacher and the parent, and the person who's responsible for, you know, handling the 504 plans, because that's a whole other system, you know, a 504 plan versus the IEP. The team looks at what accommodations would be appropriate for the student. And it could be accommodations like the student gets some extra time on assignments and tests, maybe they get a small group or individual testing because they need to focus.So those are some examples of things that we put, you know, in 504 plans, and we have students that have 504 plans and still get those accommodations when it comes to standardized and state testing, they still get those things. So, it's not like they only get them in the classroom, and then they don't get them in other things. It goes through all the different situations and circumstances that the student could have those supports.Andy: So, you mentioned that for kids who don't qualify for an IEP, sometimes you try to provide a 504 plan. What about kids who have a disability, but don't have an IEP or a 504? What are some of the things a school can do to help support those kids?Lauren: You know, a student that has an IEP, right? They have specific rights that are outlined, but every kid has all different specific learning needs, whether they have that IEP or not. So, establishing a mindset of how do we make the classroom environment, as well as the learning materials more accessible? There's things that students might need from time to time, and we just have to provide them and make sure that there's still supports that are in place there that may not need to be supports that are there long-standing.But we know we don't just like, you know, not give supports as a teacher, if we see a student struggling, we want to help. And so, I think reframing it is like, "OK, well, just because they have an IEP, only those groups of students can get help." No, like all students can get help. So, I think that there's still a way to design supports within a classroom or for students, whether they have that IEP or not.Andy: So, Lauren, I want to circle back to some really good advice you gave about encouraging parents to come to these meetings ready to ask questions and make suggestions. And listeners, one thing that can help you do this is to make sure you get a copy of your child's evaluation report before you go to that meeting. You have a right to see that report in advance. We've got a lot more information in episode three about your evaluation rights.But I want to make sure you know that you have this right in particular, because it can be really helpful to look at the report ahead of time, think about what questions you want to ask and what suggestions you want to make, so you can be an active member of the team during the eligibility meeting. Lauren, thanks so much for being with us today. I've really appreciated your input and it's been so awesome to learn about how you do your work down in Louisiana.Lauren: Yeah, thank you, I really enjoyed this conversation.Michele: My name is Michele and I live in the Bronx, New York. My oldest son was not given a diagnosis because they deemed him not eligible for special education services, because they basically said there's nothing, there's no real issue. He's just very creative, his mind needs to be stimulated, but they couldn't justify providing services. So, he was never given an IEP, he was never in special education.Andy: So, we've been talking about what adults can expect after an evaluation, an IEP, a 504, or informal supports. But what can adults say to kids about these things? And how are kids likely to react? So, to help me unpack all this, I'd like to bring in my next guest, Amanda Morin, she co-hosts Understood's "In It" podcast, about the joys and frustrations of parenting kids who learn and think differently. She's the mom of two kids who learn differently, and she has also worked as a classroom teacher and as an early intervention specialist. Amanda, welcome.Amanda: Thank you so much, Andy. And as you know, I've also attended a number of IEP meetings on my own too, right? As a parent. Andy: You've been at this table. Yeah. So, let's jump into this a bit. I mean, you know, what kind of things can parents talk to their kids about when we're talking about getting an IEP or a 504, or some of these supports?Amanda: So, I think the first thing is to know that kids have so many reactions to things, right? The same way we as parents have reactions to things, your child's gonna have a whole bunch of reactions to things, and it may not be what you expect, right? For some kids, it may be relief, "OK, phew! We're going to sit down and finally have this conversation. And maybe I'm going to feel better at school, maybe I'm going to feel like I can really do this, there's going to be more help." And a lot of parents don't expect that reaction. And so, as a parent, I think being open to whatever your child's reaction is, really matters.So, to be able to say to them "How do you feel?" instead of saying to them "Do you feel sad? Do you feel angry?" Like, don't put those emotions in their minds until they tell you what's on their minds. And I think that's important, too.Andy: Yeah. So, you're talking about their emotions relative to the reaction to all the things they're learning, which is a ton of information. And I think it's really important — you mentioned — when you ask about how they're feeling, the open-ended question, right? "What are you feeling? What's it feel like?" I mean, and I think for younger kids, they may struggle in expressing that. And yeah, I think you made a great point that you're not always going to know what to expect, because they may say things that just shock you or surprise you, or please you, I don't know.Amanda: Or they may not even care, right? Like sometimes kids don't care the way we do as parents, and we're like, "What? This is such a big deal." And your child's like, ''No, not really. Not that big a deal.'' And so, I think you can follow their lead in that situation and be like, "Oh, OK. Well, this is a big deal for me. And I'm sorry to assume that it was a big deal for you." And I don't mean that in a sarcastic way, I mean like sincerely to be able to say to your child "Oh, it feels like a big deal to me. I didn't mean to assume that it was a big deal for you too." And then sort of move on from there.Andy: For sure. For sure. So, let's say that your child's starting to express some of those, you know, unhappy emotions, that anger, or saying, "Well, this isn't true" or are feeling sort of down about it. Where do you go? How do you really navigate that?Amanda: That one's really hard. I mean, I'm just going to be honest, and say it's really hard. Because what it does is, your child is all of a sudden hearing about themselves in a totally different way, right? They're hearing about themselves, especially because unfortunately, a lot of evaluations are around looking for weaknesses, right? Looking for deficits is the word that comes up a lot. And I think the way to handle that with a child is to say, "Of course you're angry; of course you're sad. Of course this tells you about yourself in a way you hadn't thought about yourself before. But you're still you, you know. You haven't changed; the paperwork says one thing, it's just talking about you. It's a snapshot, it's a picture of you, but you're still the same person you were. And what this does is allow us to talk to the school about whether or not you're eligible for help, for additional support, for ways to make you feel like you are more you than you've ever been before." Because when kids have the support they need at a school, whether it's through an IEP or a 504 plan or informal accommodations and support, they really do feel like they get to be more of their full selves because they get to show what they know, right? In that moment, you can say "You're angry because you're not able yet to show what you know." But I think it's OK to just say, "You feel this, and we can sit with it. It's really hard, right? It's really hard." And they may be angry at you.And I think it's important to know that because you're the person delivering the information. You're the person who may have started this process. You're the person who's talking to them about this. If they're angry at you, that's hard. But I think you need to redirect it. And oftentimes that's about "I hear that you're angry, and I really want to talk to you about this. I'm not able to have this conversation while you're yelling at me." Right? ''So, we're gonna take a moment. When you can talk to me calmly, we can have this conversation.''Andy: Amanda, this is amazing advice. And I'm really glad we could do this today. Thanks so much for being here.Amanda: Yeah, thanks for having me.Andy: So, we've talked about how schools determine who is eligible for special education, and other ways schools support struggling students. We've also talked about how to ask open-ended questions to help your child talk about how they're feeling. If there's one thing you can take away from this discussion, is that you can play an active role in what happens after the evaluation. So don't be afraid to ask lots of questions until you understand what's happening and why. As always, remember that as a parent, you are the first and best expert on your child.In our next episode, we'll focus on the difference between private and school-based evaluations and why some families choose to get one or the other or both. We hope you'll join us.You've been listening to Season 1 of "Understood Explains" from the Understood Podcast Network. If you want to learn more about the topics we covered today, check out the show notes for this episode. We include more resources as well as links to anything we've mentioned in the episode. And now, just as a reminder of who we're doing all this for, I'm going to turn it over to Abraham to read our credits. Take it away, Abraham.Abram: "Understood Explains" is produced by Julie Rawe and Cody Nelson, who also did the sound design for this show. Briana Berry is our production director. Andrew Lee is our editorial lead. Our theme music was written by Justin D. Wright, who also mixes the show. For the Understood Podcast Network, Laura Key is our editorial director. Scott Cocchiere is our creative director. Seth Melnick is our executive producer. A very special thanks to Amanda Morin and all the other parents and experts who helped us make this show. Thanks for listening and see you next time.Andy: Understood is a nonprofit organization dedicated to helping people who learn and think differently discover their potential and thrive. Learn more at understood.org/mission

Understood Explains Season 3

Understood Explains Season 3IEPs: The difference between IEPs and 504 plans

Learn the key differences between two common plans for school support, and which one might be right for your child. The terms IEP and 504 plan may come up a lot when you’re looking into special education for your child. These school supports do some of the same things, but one can provide more services and the other is easier to get. And it’s important to know the differences in order to get your child the support they need. On this episode of Understood Explains, host Juliana Urtubey will break down the differences between IEPs and 504 plans, and which one might be right for your child. Timestamps [00:53] What is a 504 plan?[02:16] What’s the difference between an IEP and a 504 plan?[08:15] Can my child have an IEP and a 504 plan at the same time?[09:36] Should my child switch from an IEP to a 504 plan?[10:45] What do multilingual learners need to know about IEPs and 504 plans? [11:58] Key takeawaysRelated resources504 plans and your child: A guide for familiesThe difference between IEPs and 504 plans (comparison chart)10 smart responses for when the school cuts or denies servicesUnderstood Explains, Season 1: Evaluations for Special EducationEpisode transcriptJuliana: As you look into getting your child more support at school, you're likely to run into the terms IEP and 504 plan. They do some of those same things, but one has a lot more stuff and the other is a lot easier to get. On this episode of "Understood Explains," we explore how these plans are similar and how they're different, and which one might be right for your child. From the Understood Podcast Network, this is "Understood Explains IEPs." Today we're going to learn about the differences between IEPs and 504 plans. My name is Juliana Urtubey, and I'm your host. I'm the 2021 National Teacher of the Year and I'm an expert in special education for multilingual learners. And speaking of languages, I want to make sure everyone knows all the episodes this season are available in English y en español. Let's get started. [00:53] What is a 504 plan?OK. So, what's a 504 plan? Before we get into the difference between an IEP and a 504 plan, I want to quickly explain what a 504 plan is. This is a tailored plan that removes barriers to learning for a student with disabilities. The goal is to give the student equal access to learning. To do this, a 504 plan often includes assistive technology, meaning things like screen readers, noise-canceling headphones, or speech-to-text software. Many 504s also include accommodations, which are changes in the way things get done. A common example is getting extended time on tests or getting to leave the classroom to take short breaks. And the other thing I want to mention is that some 504 plans include services like speech therapy or study skill classes. This doesn't happen all that often, but services can be part of a 504. So, the basic components of a 504: Assistive technology AccommodationsServicesRight about now, you may be thinking that 504s sound a lot like IEPs, Individualized Education Programs. And you're right. These two plans have a lot in common and can provide a lot of the same supports. But there are some key differences. And that's what the whole next section is about. [02:16] What’s the difference between an IEP and a 504 plan?OK, so what's the difference between an IEP and a 504 plan? I'm going to focus on three key differences: First, IEPs provide special education services. Students with IEPs may spend a lot of time in general education classrooms, but the heart of an IEP is the specially designed instruction to help a student catch up with their peers. For example, a student with dyslexia might get specialized reading instruction a few times a week. The IEP also sets annual goals and monitors the student's progress towards reaching those goals. So the key thing here is that IEPs provide special education. 504s on the other hand, do not provide special education. There are no annual reports or progress monitoring with 504s. What 504s do is remove barriers to the general education curriculum. So 504s can be good options for, say, a student with ADHD or written expression disorder, who doesn't need specialized instruction but does need accommodations, like sitting in a less distracting part of the classroom, or showing what you know in a different way, like giving an oral report instead of taking a written test. To give you a more detailed example, I want to talk about a student of mine named Brian. He had a 504 plan to help accommodate his vision impairment. To make the plan, I talked to Brian about what he needed, and I worked with the school's assistive technology department to find some helpful tools. We learned that Brian had an easier time reading and writing when he used a slant board to help raise up the paper. He also benefited from having what's called "augmented worksheets." Rather than having a bunch of math problems on one sheet of paper, Brian would get several sheets, so the problems were spread out and enlarged and he could see them better. With these supports, Brian could do all the work on his own. And to create his 504, a school staff member wrote up the plan and included my suggestions for accommodations and assistive technology. And the only thing we needed to get started was his parents' consent. And this brings me to the second big difference between IEPs and 504s. They're covered by different laws, and IEPs come with a lot more rights and protections than 504s do. So, for example, IEPs are covered by the federal special education law, which is called the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, or IDEA. This law is very focused on education and one really important detail about IDEA is that it says parents are an equal member of the team that develops the IEP. But that's not true for 504s. 504 plans are covered by an important civil rights law called The Rehabilitation Act of 1973. This law bans discrimination against people with disabilities in several key areas. It has a big section about employment. It has a big section about technology, and it also has a big section about education. This is where the name "Section 504" comes from. So, IEPs and 504 laws are covered by different laws. And one difference between these laws is how much schools are required to involve parents. With a 504 plan, parents don't have to be equal members of the team. Schools don't have to involve parents in creating this kind of plan. They just need a parent's consent before starting to use it. Although I want to mention that many schools encourage families to help create the 504 plan, schools aren't required to involve them. There are also different rules about what schools need to do to make changes to these plans. With 504s, schools have to let parents know if a significant change is being made to the student's 504 plan. But the school doesn't have to send a written notice about this. With an IEP, schools have to send parents a letter and have a meeting with the full IEP team before they can change the IEP. And if parents want to dispute the changes, the school has to keep the current plan in place while the dispute gets resolved. With either of these plans, families can ask to make changes, but families have more rights and protections with IEPs. We'll talk more about IEP rights and dispute resolution later this season. There's a third big difference I want to mention. IEPs are harder to get than 504s. The process for determining who is eligible for an IEP takes more time and it involves more steps. Students need to have a disability to qualify for either plan, but to get an IEP, kids need to go through the school's comprehensive evaluation process. You can learn all about this process in season 1 of "Understood Explains."OK, so kids need to be evaluated by the school to get an IEP. By contrast, kids don't need to get evaluated by the school to get a 504. This kind of plan is easier to get, but it's less likely to include specialized instruction. So for example, let's look at students with ADHD. The main thing they'd need to qualify for a 504 is a diagnosis from their health care provider. But to qualify for an IEP, those same students would still need to go through the full evaluation process through their school. It's the same thing with dyslexia or depression or a hearing impairment or any type of disability. It's pretty quick to start getting accommodations and assistive technology through a 504. It takes longer to see if a child qualifies for an IEP. We're going to talk more about this later this season, but for now, I want to briefly mention the two eligibility requirements to qualify for an IEP. The evaluation team has to determine that you have a disability and that the disability impacts your education enough to need specially designed instruction. OK, that's a lot of info, let's summarize quickly before we move on. 504 plans are meant to remove barriers in general education classrooms. IEPs provide specialized instruction. They take longer to get, but they come with more supports, including legal protections and annual goals. [08:15] Can my child have an IEP and a 504 plan at the same time?Can my child have an IEP and a 504 plan at the same time? Yes, it's technically possible to have both an IEP and a 504 plan, but it's unlikely your child would actually need both. That's because an IEP can include everything that's in a 504 plan and more. For example, if your child has speech impairment and ADHD, the IEP can include speech therapy as well as accommodations related to that ADHD, like reducing distractions in the classroom and helping your child get started on tasks. There are, however, some situations where it might make sense to have both kinds of plans. For example, if a child has an IEP and gets a temporary injury, like a broken hand and needs some writing accommodations until it heals. Rather than going through the hassle of adding and removing those accommodations from an IEP, the school might choose to add them via a 504 plan. Another example of when a school might use both an IEP and a 504 plan, is if the student has a medical condition that doesn't directly impact academics, like a peanut allergy. So, there are some special cases where both plans might be OK, but in general, if your child has an IEP, keep it to that single plan. It's easier for you and for teachers to manage just one plan instead of two. [09:36] Should my child switch from an IEP to a 504 plan?Should my child switch from an IEP to a 504? So, this happens a lot, and it's not necessarily a bad thing. Maybe your child has made a lot of progress and no longer needs specialized instruction. For example, let's say your child has dyslexia and their reading skills have improved, and now all they need are tools or accommodations. This can include extra time on tests and digital textbooks that can highlight the text as it's being read out loud. Both of the supports could be covered in a 504, but if you think your child still needs specialized instruction, you can advocate to keep the IEP. We'll get into more specifics about this later in the season, but for now, I'll just put a link in the show notes to Understood's article on what to do if the school wants to reduce or remove your child's IEP services. The other thing I want to mention is that it's possible to move from a 504 plan to an IEP, but your child will need to be evaluated by the school and it takes longer to qualify for an IEP. We have a whole episode coming up about deciding who qualifies for an IEP. [10:45] What do multilingual learners need to know about IEPs and 504 plans?There are two really important things that multilingual families need to know about IEPs and 504s: First, getting your child an IEP or 504 plan does not put you or your family members at any greater risk of immigration enforcement. It's completely understandable that families with mixed immigration status might have concerns about getting formal supports at school, especially if it involves filling out paperwork with personal information. But all students in the United States have a right to a free, appropriate public education, no matter their immigration status. Plus, schools are considered sensitive locations, which means immigration enforcement cannot take place there. I'm going to talk more about this in a later episode that is all about multilingual learners. But for now, the one thing I want to mention is that formal supports in school, whether they're part of an IEP or a 504, should happen in addition to being taught English as an additional language. It's not an either or situation. You don't have to choose between disability support and language instruction. If your child needs both, your child can and should get both. [11:58] Key takeawaysAll right. That's all for this episode. But before we go, let's wrap up with some key takeaways. 504 plans are covered by a civil rights law that bans discrimination against people with disabilities. 504s remove barriers to general education. IEPs are covered by special education law and provide specially designed instruction and services for kids with a qualifying disability. Both plans can provide accommodations and assistive technology. And last but not least, specialized instruction is a core feature of IEPs, but it's not very common in 504 plans. That's it for this episode of "Understood Explains," tune in for the next episode on IEP myths. You've been listening to "Understood Explains IEPs." This season was developed in partnership with UnidosUS, which is the nation's largest Hispanic civil rights and advocacy organization. Gracias, Unidos! If you want to learn more about the topics we covered today, check out the show notes for this episode. We include more resources as well as links to anything we've mentioned in the episode. Understood is a nonprofit organization dedicated to helping people who learn and think differently discover their potential and thrive. Learn more at understood.org/mission. Credits Understood Explains IEPs was produced by Julie Rawe and Cody Nelson, with editing support by Daniella Tello-Garzon. Video was produced by Calvin Knie and Christoph Manuel, with support from Denver Milord.Mixing and music by Justin D. Wright.Ilana Millner was our production director. Margie DeSantis provided editorial support, and Whitney Reynolds was our web producer. For the Understood Podcast Network, Laura Key is our editorial director, Scott Cocchiere is our creative director, and Seth Melnick is our executive producer.Special thanks to the team of expert advisors who helped shape this season: Shivohn Garcia, Claudia Rinaldi, and Julian Saavedra.

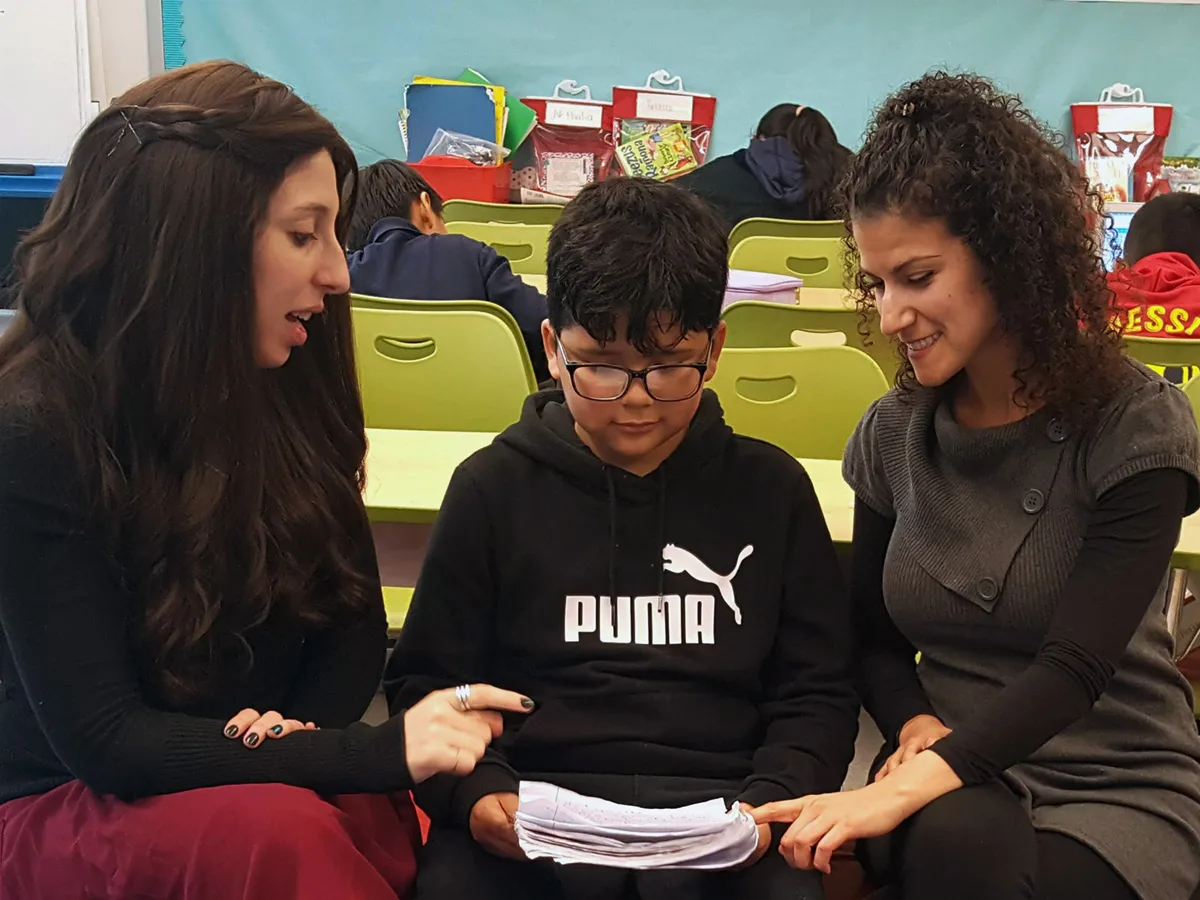

Teacher to teacher: How I help students see support staff as teachers

“I don’t want to go to speech therapy,” says one student. “You’re not my teacher. I don’t have to listen to what you say!” cries another student to a paraprofessional. Speech therapists, ESL teachers, paraprofessionals, and school counselors are just some of the adults who support my students each day. I see them as my support team, and they help me create a classroom filled with respect, empathy, learning, and fun. But my students don’t always see the importance of these other teachers. As a special education teacher, one of my goals is to support my students in developing genuine relationships with all the adults who support their learning. Here are four ways I help my students see support staff as their teachers, too: 1. I refer to them as teachers. When introducing students to someone from my support team, I refer to them as a teacher. “What did you learn with your speech teacher today?” sounds very different from, “What did you do in speech therapy today?” It changes students’ perspectives on their relationships with support staff. I recognize that these adults need to build their own relationships with my students. But this small shift in language can be a start. 2. I help students’ families understand the role of my support team. I want my students’ families to see my support team as teachers, too. This helps create a cohesive experience between home and school. I also want families to feel comfortable asking them any questions they have. Families may not always understand why their child needs services and who provides them. So at the beginning of the school year, I communicate with families, sharing bios (translated into various home languages) and photos of my support team. I reinforce that this staff person is a teacher and encourage an open line of communication with all their child’s teachers, not just me. 3. I regularly consult with my support team about our curriculum. When my students work with paraprofessionals, specialists, or other staff members, I don’t want it to feel like a separate lesson. Rather, it should be an extension of what we’re learning in the classroom. I do this by making sure my support team understands the curriculum and students’ progress with it. Before each new unit, I meet with my support team. I explain the curriculum, ways to support students, and how a specific specialist’s goals might align with what we’re working on. I do this outside of teaching time like at preps, lunches, or before or after school. I know it can be challenging to find this extra time to meet, but it has been a worthwhile investment for me. Here’s an example of how I make working with support staff an extension of our classroom. My student had a session with the occupational therapist. I said to the student, “In class, we’re working on publishing our writing. You’re going to work with Ms. A. on making sure that this published piece is clear so your friends and family can read it.” Before the session, I talked with Ms. A., the occupational therapist. We discussed how the student’s fine motor skills prevented publishing legible work, which was one of their IEP goals. Because of our discussion, the student was able to publish the essay while working on pencil grip and legible writing. 4. I make sure all work matters in our classroom.My students know that their work is an important step toward completing a goal. When they know that all their work matters — no matter who supports it — they’re more likely to engage. They also know that we’ll share and reflect on completed work, regardless of the support received to produce it. It changes how kids feel about a session with a specialist or small group time with a paraprofessional. It may have felt like a chore before, but now it’s something they’re more eager to do.For example, when my students were working on verbal responses, one had prepared hers with a speech teacher. She knew that the next day the class would be practicing their responses with peers. Because the student prepared and practiced during her speech session, she felt ready for the next day. The same applies to my support team. They know I appreciate what they do and that I support their work. They know they can count on me to reinforce the skills and strategies they teach. Even though I’ve worked hard to develop strong relationships with my students, those relationships don’t automatically transfer to the other adults my students interact with. These strategies help me foster relationships between my students and my support team. They help students see that each teacher — including paraprofessionals, specialists, and other support staff — guides them in their learning journey. Any opinions, views, information, and other content contained in blogs on Understood.org are the sole responsibility of the writer of the blog, and do not necessarily reflect the views, values, opinions, or beliefs of, and are not endorsed by, Understood.

Understood Explains Season 1

Understood Explains Season 1What to expect during a special education evaluation

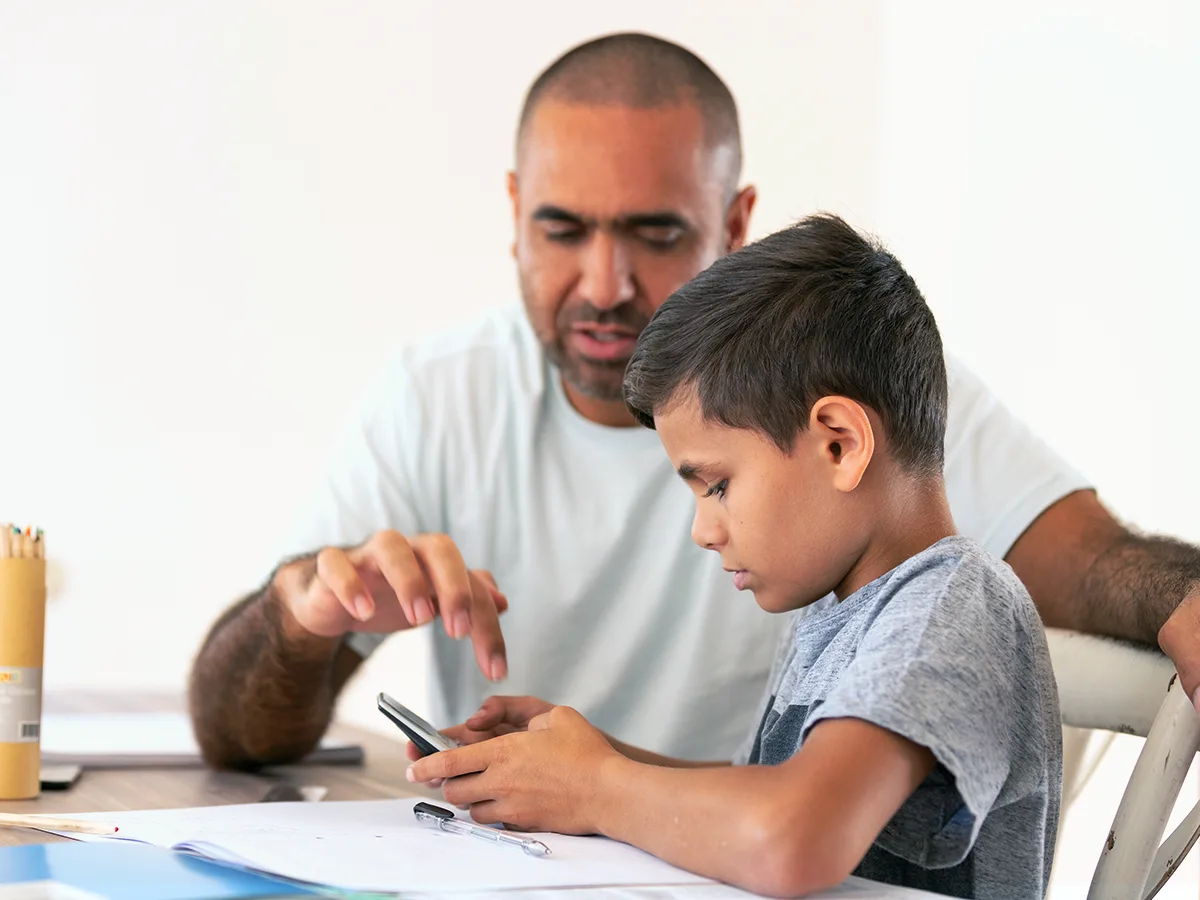

What happens during the evaluation? And what role do families play? Learn how to help shape the evaluation plan and help your child get ready. What happens during an evaluation for special education? Who plans the assessment activities? And what role do families play? This episode of Understood Explains covers all of this and more.Host Dr. Andy Kahn is a psychologist who has spent nearly 20 years evaluating kids for public and private schools. His first guest on this episode is Brittney Newcomer. She is a nationally certified school psychologist. Andy and Brittney will explain:What to expect during an evaluationWho plans the assessment activities How you can help shape the evaluation plan for your childAndy’s second guest is parenting expert Amanda Morin. They’ll share tips on how you can help your child get ready for the evaluation. (Hint: The answer does not involve any studying.) Related resourcesPreparing for an evaluationThe school evaluation process: What to expectWho’s on the evaluation team at your child’s schoolShould your child study for a special education evaluation?Download: Sample letters for things like accepting or rejecting an evaluation planVideo: Inside a dyslexia evaluationEpisode transcriptJaime: I am Jaime. I am living in Huntington Valley, Pennsylvania, which is right outside of Philadelphia. My son is Jonah; he has ADHD. He has a visual impairment, and he has just a general learning disability in basically every subject. So, the whole process of getting Jonah evaluated and acquiring all the necessary materials that the school needed was a complete mess. Every time I thought I was done, and we were good to go, they called me up and said, "Oh, we need another document" or "Oh, we need another record." It just felt like it was never-ending.Andy: From the Understood Podcast Network, this is "Understood Explains." You're listening to Season 1, where we explain evaluations for special education. Over 10 episodes, we cover the ins and outs of the process that school districts use to evaluate children for special education services. My name is Andy Kahn, and I'm a licensed psychologist and an in-house expert and understood.org. I've spent nearly 20 years evaluating kids for both public and private schools. I'll be your host. Today's episode is about what to expect during the evaluation itself. We're going to explain how you can help the school get ready to evaluate your child and how you can help your child get ready. No, I promise this won't involve any studying. First, let's hear more of Jaime's story.Jaime: So, the only way at all in which I was involved in his evaluation and planning process is they sent home basically like a questionnaire that the parent has to fill out in terms of behaviors that happen in the home with our child — I guess that was tight tied more towards the ADHD diagnosis, you know, asking all sorts of questions about impulsivity and social interactions with other people. I actually did remind them several times, "By the way, Jonah is different than most children in that he does have a visual impairment, and please test him to see if he qualifies for vision therapy because I know that you can get vision therapy at public schools." And also, I had said to them, you know, "At his previous school, he had speech therapy." I did remind them of that and pushed hard that I wanted to make sure that he got tested for all of those things and got those supports if they found that they were necessary.Andy: It's very common for families to wonder about or worry about what happens during an evaluation. There shouldn't be any surprises for you or for your child. As a member of the evaluation team, you have a right to know about and help shape the evaluation plan for your child. My first guest is going to help me unpack all of this. Brittney Newcomer is a nationally certified school psychologist based out of Houston, Texas. Like me, she’s been in schools quite a long time. She's also a mom of two and an Understood expert, who has a master's degree in special education. Brittney, welcome.Brittney: Thank you, Andy.Andy: So, let's start with the big picture. Different kids need different evaluation plans, right? So, for example, some kids need to be evaluated for speech therapy, and some kids don't. But many evaluations tend to have one thing in common. And that's an educational evaluation, or sometimes you hear it called psycho-educational evaluation. This is where psychologists like you and me, Britt, we do some cognitive testing in areas like reasoning, memory and processing speed. We also look at like academic skills, reading, writing, math, and we look at social, emotional, and behavioral functioning. So, with these key areas in mind, academic, social-emotional, behavioral, how do you go about personalizing an evaluation plan for your kids?Brittney: Yeah. So, when I approach planning and evaluation, you start with the referral reason. So why are we requesting this evaluation? And once we have that really clear picture of what the referral reason is, that's where I start to plan my evaluation. So, I gather as much data as I can first, you know, school records, information from the teacher, I typically talk to the parent. But then I sit down, and I plan the evaluation, which is essentially looking at some broad measures first, so to really give us a big picture of how the student is performing. So, when I say broad measures, I'm talking about things like behavioral scales that look at a broad spectrum of behavior.Andy: So, like questionnaire kind of scales?Brittney: Yeah, exactly.Andy: All right, so let me try to sort of break some of this down. So, when we talk about like referral reasons, what are some of the questions that you're trying to answer?Brittney: So, the first referral question that I usually ask is, in what ways is the student struggling? And then I also ask, on the flip side, in what ways is the student being successful? Where are they not struggling? I also look at factors that could be contributing to the student struggling. So, this could include things that are going on at home, this could include global pandemic, so just really looking at those factors that could be influencing the student's performance at that time.Andy: So, I think you know when we use the word like comprehensive, you know, the idea that we're looking at a lot of bits and pieces of what this child's whole life is about. And for some families, that's a little bit anxiety-provoking, right? If they're having challenges, let's say in school, but you come in with a big broad question like this, how do you navigate that with your families when you're looking at the big picture? And they might be thinking, "Oh, I thought you were looking at my kid's reading" or some other specific challenge.Brittney: I try to approach evaluations and working with families and how I sometimes explain it to them, is that you know, if we're using an analogy, like a jigsaw puzzle, so when we know what that problem is, at the end of the evaluation, we really want kind of a comprehensive, full picture of what's going on in the child. And the only way for us to get there is to have different pieces to put together to be able to see that full picture of what's going on with the child. So again, emphasizing we're not just talking about areas of need, and disability, we're also talking about strengths as well. And so, I do emphasize that with families right off the bat. But in order for us to get that comprehensive picture, we have to have their side as well, and what could be impacting the child. Because that's, in my opinion, one of the most important pieces is the input from the family.Andy: Yeah, I think that makes a lot of sense. When you talk about your evaluation team, do you also have other members like teachers in the team? Or who else is at the table outside of those, you know, multidisciplinary, other evaluators, perhaps?Brittney: Yeah, ideally, teachers would be at the table. Speaking in reality, and teacher schedules, it's often difficult to get them at that initial meeting. But their input is always provided; teachers can provide their input via writing, or we can call them into a meeting via Zoom and allow them to share their input with the classroom teachers are seeing on a day-to-day basis. It's a huge piece of that puzzle that we need to just consider during that initial referral meeting.Andy: Absolutely. And depending upon your state, there may be requirements for the people who are around the table. So, for example, in the state of Maine, we are required to have a regular education teacher, a special education teacher, and an administrator around the table. Brittney, what are some of the timelines that you guys are honoring in Texas? You know, in Maine, we have a 45-day timeline from the day the referral is signed to having a completed evaluation. And I think the federal law, maybe 60 days, what do you folks use for your timelines in Texas?Brittney: We have 45 days to complete the evaluation and have the report written, we then have an additional 30 calendar days, so not 30, school days, 30 calendar days to have that first meeting, IEP meeting, to review the results and determine eligibility.Andy: So, for folks who are concerned about this for your individual states, you know, take a look at our page for this podcast and you'll see we've got some state-specific information there for you folks. As we can see, there's a little bit of variation across states. And it can be a little bit confusing, but you can certainly get some of that information from your own school staff. So, let's move on to some of the, you know, we had some, some brief conversation about the kinds of tests that you've been using. And maybe we can talk about how the process might look somewhat differently for different kids. You know, they don't all take the same tests. And because we're looking for different things, maybe we can talk a little bit about some of those specific kinds of tests.Brittney: As a school psychologist, I have given many different types of cognitive intellectual tests. So basically, you know, one-on-one evaluations that look at how students learn. And I have, I know the differences and the different types of tests, like I do know that some are more hands-on, I know some that are heavily weighted in verbal input. And so, for a younger student, I really do, most of the time, like a very hands-on interactive type of testing, then sitting down one on one looking at an easel is very difficult for them. So, an easel would be just like, you know, cardstock with a card that a student would respond to, but there are certain tests that are very hands-on, and I know that's much better for my younger students. So, I'd say that's my first difference that may occur is what testing could look like for a younger student than what it would look like for an older student.Andy: Sure. And I think when you talked about intellectual or cognitive, you know, for some people, we're looking at things like getting IQ scores, and I think it's very important to keep in mind as a parent, that these scores are really just designed to look at how your child is solving problems engaging in some of these very specific learning tasks. And as Brittney was saying, some of them might lean to more hands-on activities at times, some might be more language-like question and answer that are verbal tests. And again, for most of our, especially for our young kids, we're trying to establish something that we call a baseline. A baseline is getting like that first score. Okay, where is this child starting right now on the scale? And we look at it over time, because so much of our testing is a moment in time, it's a snapshot. Brittney, talk to me a little bit about the educational part. We've sort of talked a little bit about the IQ testing, or the cognitive testing, fairly similar words. But what else tweaks that sort of educational piece? Because you've described a lot of big-picture stuff. What about some of those specific pieces?Brittney: Yes, so we also look at how the student is performing academically and with their achievement. So, when we look specifically at achievement, there are standardized tests that you can give that gives a snapshot of how the student is performing in reading, writing, and math. It's not the only piece though when you're looking at how a student's performing academically, and that's something I stress to parents. We're also looking at grades, we're looking at the student's response to the interventions that have been put in place by the school. So, for example, if a student is struggling in reading, and they've had a very specific reading intervention put in place, how have they responded to that intervention? Observations is actually a big part of this as well — seeing the student in the class where they are struggling, is a big piece of this.Andy: So, we've been talking about the cognitive and educational parts of the psycho-educational testing, how do you approach the behavioral or social-emotional parts of psycho-educational testing?Brittney: Specifically, when I approach the psychological component, this involves a lot less of one-on-one testing of the student, it involves a lot of observation, so seeing the student in different parts of their day. So how are they in the cafeteria? How are they in their classroom during a reading lesson? How are they during a more, or a time when it's less structured like music class? So really seeing a comprehensive view of their day in different settings. Observations are a huge piece of a psychological evaluation. It also includes interviews, so talking with the parent, talking with the student, and then also talking with the teachers.Andy: So, what do you think families can do to help plan and get the right testing for their child?Brittney: So, when we obtain consent, so consent saying we can move forward with testing, we typically talk about the major categories and some proposed testing measures that we'll use. This is where I really, really advocate to families to ask questions, find out exactly what type of what we mean, when we say cognitive testing. I really try to encourage families to ask questions throughout the process. So, making kind of checkpoints with the family. Okay, here's where we're at, here's what I'm thinking about in terms of next steps, what do you think? And just get, making sure, that their input is a part of that process.Andy: Britt, let's talk a little bit about ADHD. Now, many families want to know if a school evaluation can diagnose their child with ADHD. But typically, school psychologists can't make a clinical diagnosis. So, you need a specific type of licensing like the one I have to make a diagnosis.Brittney: When the referral question is around attention, impulsivity, when I am thinking that ADHD needs to be considered, I do have the ability to give scales rating scales, observations specific to ADHD. However, when I write in my report, I write about the characteristics that I'm seeing of ADHD versus the child has ADHD. In Texas, ADHD falls under Other health impairment and an Other health impairment has to be endorsed by a clinical doctor. If the child has an outside diagnosis already, it's a fairly simple process to where we send this form to the doctor, the doctor signs that yes, the student has ADHD, and that becomes part of their eligibility in special education. Now, when the child does not have an outside diagnosis already, that's where it becomes a little bit more complicated. So, I will describe what I'm seeing, I will describe the characteristics that I'm seeing, and then it is up to the family at that point if they do want to pursue the actual diagnosis of ADHD. So, they would then take the step to talk to a doctor about getting that official diagnosis.Andy: Yeah. So, Brittney, you mentioned that schools need to get parents' consent; parents need to agree to the evaluation plan before the school can move forward. So, let's talk for a minute about parental rights. This season of "Understood Explains" has a whole episode about evaluation rights. But for now, I want us to touch on parents' rights during the planning part of the evaluation process. You know, when we think about English language learners, or homeschooled or private school students, are there any things you can share about their rights? Or how this part of the process might be different for them?Brittney: Yes. So going back to that informed consent. For our English language learners, their families have the legal right to have that information presented in their native language. So super important and pretty obvious that we would want, you know, them to be informed in the language that they understand. But it is something that not all families know is a legal right. So, the other piece for our English language learners, is that there has to be a specialist that knows about English language acquisition. So, second language acquisition as part of the evaluation team. So, this was actually recent, I believe it was November 2021, federal guidance that they asked for a member of the evaluation team to have expertise in second language acquisition because we shouldn't be making a determination about why a student is behind academically if we aren't considering where they are acquiring English as their second language.Andy: Yeah, that's absolutely huge. The idea that being able to evaluate somebody's reading or writing skills, for example, when they're not a primary English speaker is an unfair set of criteria. The reality is that not all standardized tests are fair for people who don't speak English as a primary language or people who are from a different culture, other than the dominant culture that created that evaluation tool. And we'll talk about the idea of culture-fair evaluations in other episodes, but this is what we're referring to here. You should not be at a disadvantage because you are not a predominant English speaker, or you're in the process of learning English as your second or third language for that matter. So huge. Thank you for that, Brittney. One other population group that I've dealt with in terms of the evaluation process was homeschooled and private school students within my public schools. Those students maintain the same legal right to free evaluations. And yet we within the public schools typically provided that assessment. What's that process been like for you? Have you had to do those within your school systems?Brittney: So yes, it is the same process where the public school is responsible for providing that evaluation. We provide the evaluation for the family and the school, but the school isn't necessarily legally obligated to provide all the services that we recommend, based on what the student’s needs are. So that is a nuanced thing that I've experienced with private school evaluations.Andy: Brittney, thanks so much for being here today. I can't thank you enough for all your expertise in time.Brittney: Thank you so much for having me.Jaime: So in order to prepare Jonah for the evaluation process, and the fact that there might be people sitting in and observing him, I basically just said to him, "Listen, you're starting a new school, you know, they're looking to see if you need vision therapy, they're looking to see if you need speech therapy, there's probably going to be some people coming in to either do some testing or just kind of watch you as you're learning. And I just want you to just be yourself and do what you normally do and let them do what they have to do, and they will find the best possible plan for you to make sure you get the best education possible." So, I just kind of laid it all out for him just so he knew what was happening, but he was a champ through the whole process and didn't even basically mention it at all, because he's so resilient.Andy: We've been talking about how a team of adults does a lot of planning before the evaluation. What can adults do to help kids be ready for the evaluation or assessment process? My next guest is Amanda Morin. She co-hosts Understood's "In It" podcast about the joys and frustrations of parenting kids who learn and think differently. So, in talking about what to expect during this process, how do you help your child know what to expect? What kind of things do you suggest that we do to help them through that process?Amanda: I think it's really important to really dial down anxiety for kids because they feel like they have to perform. I mean, regardless of how old a child is, they always feel like they're on display, and they have to perform. And especially when to get into middle school kids always feel like that anyway, right? But, when they're singled out in a way, they feel like they, they have to do a certain thing. And so, I think it's important to be able to say to your child, "There's really no expectation of you here; the expectation is that you're here, and you're going to participate." And it's really great to be able to say, "You know what? You don't have to study, these are not the kinds of things you have to study for; we're not expecting you to know all the capitals of all the states, there's no expectation that you have to know certain things."Andy: Yeah, I'd say that, you know, when I talk to kids about the testing process, I'll always say to them, these activities are designed for kids through this entire age range. So, if I have an eight-year-old in the room, I'll say — so when we get to things that maybe a 10,12,14-year-old is supposed to know — "We're pretty sure that they're going to be hard for you, you might not even know what to do. So, keep in mind that as we go, sometimes things are going to get harder, sometimes things are going to be frustrating. And when you find that's happening, we know that it's working, and none of those things last forever. I will tell you, you're only going to be frustrated for so long until we move on to something else. We're going to do that for maybe three or four minutes, and then we'll move on."Amanda: I think that's really good information for parents to have too, to be able to say to your child, there's going to be times where you're frustrated, there gonna be times when the person you're talking to can't tell you whether it's right or wrong, no matter how many times you ask them, they're not going to be able to tell you. And that's because that's their job. And I think sometimes, it's really important for parents to make sure that they are proactively saying to kids, "This is not about how smart you are, this is about what you're really good at, and what you have some trouble with. And we want to really know that so you can feel better about yourself, right?" And that's part of this. It's not just about what can we do to support kids in classrooms? It's also about what can we do to make sure kids feel better about themselves? And so, I think proactively addressing that is really important, too.Andy: Yeah. You know, I think one of the pieces on the anxiety front — I want to dial back here for a sec — routinely, I will ask a parent, how does your child need preparation to know in advance that I might come in, grab them on such and such a day? Or is your child the kind of kid who would prefer to go with the flow and not have to anticipate this? Because some kids might ruminate about it and think and think and think, and not be able to focus on anything else. So, I think that's always an important thing for me when I talk to parents in advance of bringing their child in.Amanda: So, really good point, I think the other component of that, too, is if you have a child who's going to think about that over and over again and be like, wondering about it, and then your schedule changes. So, you know, working in schools, schedules change periodically, and things change up. And if you're not able to go into the classroom and talk to that kid that day, that's a child who might worry, what happened? Why did that not happen today? So, I think that's a really good point, is to make sure that you understand whether or not your child's the kid who needs that advanced warning. When it comes to anxiety, too, it's also important to separate your own anxiety from your child's anxiety, right? It's really easy as a parent to say, "I'm anxious, so my kid is anxious." But that's not always the case. And so, tuning in to whether or not your kid is actually pretty laid back and is not going to worry about this, you can just say, by the way, remember, we may have talked about evaluation, you may have already told them this is coming you may not have, so this may be the first conversation you're having. But to be able to say to them, "Oh, just wanted to give you a heads up," instead of like, "This is a thing that's happening today and I'm very anxious about it and I'm going to impart that anxiety to you."Andy: So, I think Amanda, you've really covered a lot of this. Is there anything specific though, that you think maybe we haven't covered about things you would avoid saying to your kids about what to expect in this process?Amanda: I would avoid saying to your child, "This really matters. This is really important." Right? That's a lot of pressure. That's a lot of pressure on a kid. And I think that kids who have been in school for a while, are used to taking tests or doing homework assignments. And knowing within a couple of days how well they did on that. And so, I think it's really important to let your kid know, your child know, that we're not going to know right away, right? The evaluator may have or the person you sat down with into those activities with may have an idea of what this means, but we're not going to have that information right away. Don't worry about it. You know, don't worry about it, you did the best you could do, and we'll see what comes out of it.Andy: So, we've talked about what happens during an evaluation, how you're part of the team that plans it, and how you can help your child get ready. If there's one thing you take away from this discussion, is that you can play a very active role in helping your child and the school, get ready for the evaluation. Don't be afraid to ask questions about what will or won't be part of your child's evaluation, and why. As always, remember that as a parent, you're the first and best expert on your child. In our next episode, we'll dive into what the evaluation results may look like and explain key terms to help you understand what the results mean for your child. We hope you'll join us.You've been listening to Season 1 of "Understood Explains" from the Understood Podcast Network. If you want to learn more about the topics we covered today, check out the show notes for this episode. We include more resources as well as links to anything we've mentioned in the episode. And now, just a reminder of who we're doing all this for; I'm going to turn it over to Lee to read our credits. Take it away, Lee.Lee: "Understood Explains" is produced by Julie Rawe and Cody Nelson, who also did the sound design for this show. Briana Berry is our production director. Andrew Lee is our editorial lead. Our theme music was written by Justin D. Wright, who also mixes the show. For the Understood Podcast Network, Laura Key is our editorial director. Scott Cocchiere is our creative director. Seth Melnick is our executive producer. A very special thanks to Amanda Morin and all the other parents and experts who helped us make this show.Andy: Understood is a nonprofit organization dedicated to helping people who learn and think differently discover their potential and thrive. Learn more at understood.org/mission.

Unilateral placement: Moving from public to private school

Maybe public school isn’t working for your child. The evaluations, the IEP, the small classes, speech therapy, and accommodations are all in place. And yet, your child is still falling behind. You feel you’ve got to make a change — and you’ve found a special private school with a great track record of working with children like yours. You want to move your child to a private school. But will the public school district pay for the hefty tuition? The answer is maybe. Federal law guarantees a free appropriate public education to children with learning and thinking differences. So if your child isn’t making progress in public school, the question is, Is the education “appropriate” — in other words, is it working for your child? When a parent moves a child to a private school to get better special education, that’s called “unilateral placement.” But if you don’t get the public school’s approval ahead of time, the school district doesn’t have to pay for private school. It’s important to do your homework before you make a change. A little extra research could give you the best chance of having the public school district pay for private school. Getting adviceYou might want to talk to an advisor at your state’s Parent Training and Information Center. Or get in touch with a parent advocate or lawyer before you make any move. They can explain your rights and share information about other cases like yours. Notification requirementBefore you enroll your child in private school, tell the public school about your plans. The best way is to send them a written letter 10 business days before you make the switch. This is required by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act if you want the public school to pay for the private school. A school can legally deny funding if you don’t share concerns in advance. So it also makes sense to tell the school at an IEP meeting or a progress meeting that your child isn’t making progress and you plan to switch to private school. It’s always a good idea to document your concerns in writing, too. There’s still no guarantee the district will agree to pay, but at least you’re following the law. Emergency placementIf you can prove that you needed to make an emergency move to private school, the school district might consider your request to pay for it even if you haven’t given the 10-business-day notice in writing. Such cases, however, are rare. Private school, public funds A due process hearing will be held by a hearing officer or a court to decide whether the school district should pay for your child’s private school education. You’ll be asked to prove your child was not learning in public school and wasn’t getting FAPE — a free appropriate public education. You will want to hand over school records, such as progress reports, report cards, emails to teachers and anything else that supports your claim. Another idea is to wait until you can prove your child is doing well in private school before you ask the public school to pay. Often, school districts fight requests to pay. But if the hearing officer or court sides with you, the district will have to pay.

Understood Explains Season 3

Understood Explains Season 3IEPs: The 13 disability categories